ABSTRACT

Objective:

To understand how the nursing academics experience the process of taking care of bereaved families after a suicide loss, to identify the meanings of the experience and to build a theoretical model.

Method:

Qualitative study that used symbolic interactionism and grounded theory. Open interviews were held with 16 nursing academics. Data were analyzed according to the constant comparative method.

Results:

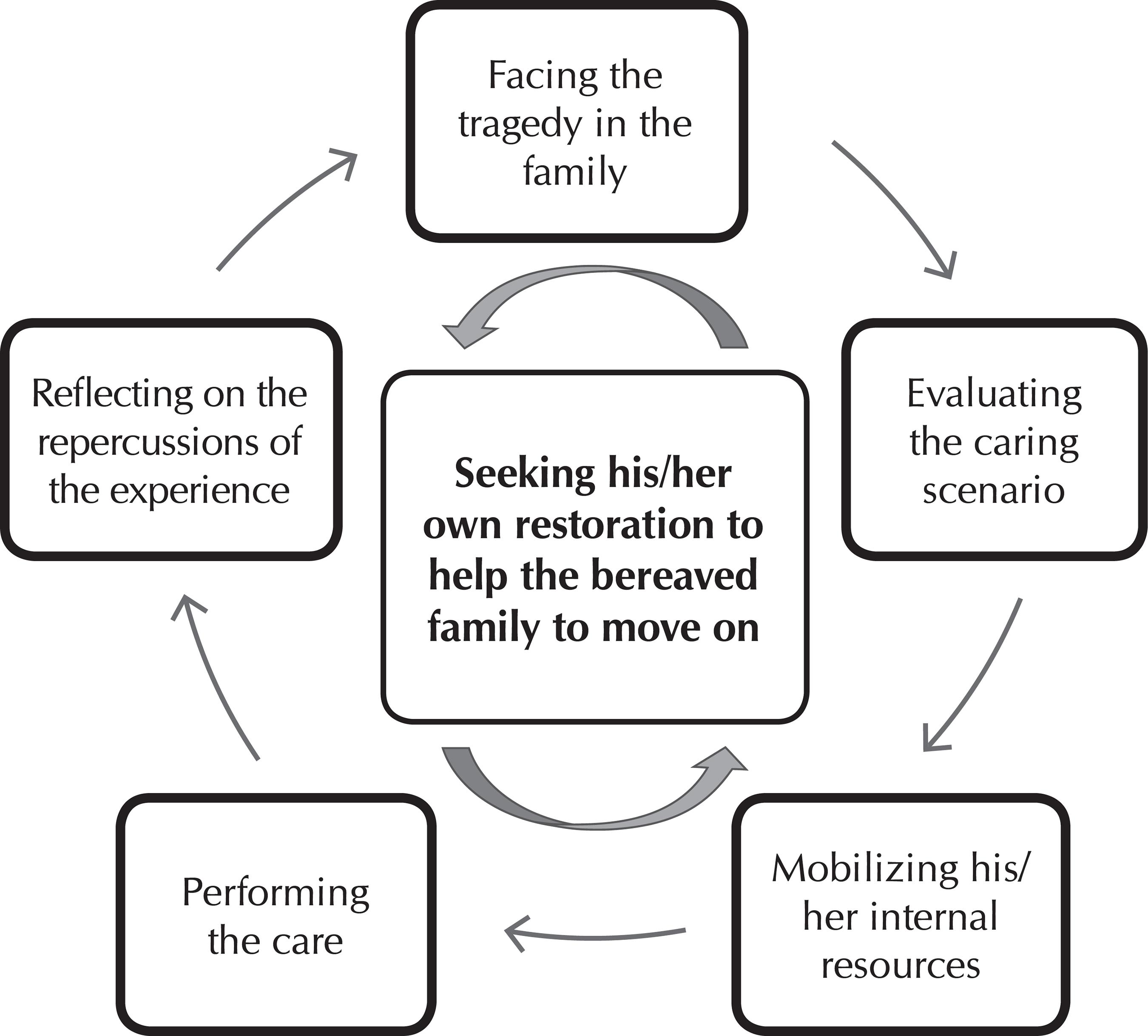

The phenomenon seeking his/her own restoration to help the bereaved family to move on is represented by the theoretical model composed by the categories: facing the tragedy in the family, evaluating the caring scenario, mobilizing his/her internal resources, performing the care and reflecting on the repercussions of the experience.

Final considerations:

The process represents efforts undertaken by students in the pursuit of the family’s restoration to provide the best care toward them, through embracement, listening, sensitivity and flexibility, so it creates opportunities for the family to strengthen and plan their future.

Descriptors:

Suicide; Family; Grief; Education, Nursing; Attitude to Death

RESUMEN

Objetivo:

Comprender cómo los académicos de enfermería vivencian el proceso de cuidar de familias enlutadas después de una pérdida por suicidio, identificar los significados de la experiencia y construir un modelo teórico.

Método:

Estudio cualitativo que utilizó interaccionismo simbólico y teoría fundamentada en los datos. Se realizaron entrevistas abiertas con 16 académicos de enfermería. Los datos se analizaron según el método comparativo constante.

Resultados:

El fenómeno buscando su propia restauración para ayudar a la familia enlutada a seguir adelante, es representado por el modelo teórico compuesto por las categorías: enfrentándose con la tragedia en la familia, evaluando el escenario de la asistencia, movilizando sus recursos internos, conduciendo el cuidado y reflexionando sobre las repercusiones de la experiencia.

Consideraciones finales:

El proceso representa esfuerzos emprendidos por los estudiantes en la búsqueda de su restauración para ofrecer el mejor cuidado a la familia, por medio de acogida, escucha, sensibilidad y flexibilidad, de modo que se fortalezca para planificar su futuro.

Descriptores:

Suicidio; Familia; Pesar; Educación en Enfermería; Actitud Frente a la Muerte

RESUMO

Objetivo:

Compreender como os acadêmicos de enfermagem vivenciam o processo de cuidar de famílias enlutadas após uma perda por suicídio, identificar os significados da experiência e construir um modelo teórico.

Método:

Estudo qualitativo que utilizou interacionismo simbólico e teoria fundamentada nos dados. Foram realizadas entrevistas abertas com 16 acadêmicos de enfermagem. Os dados foram analisados conforme o método comparativo constante.

Resultados:

O fenômeno buscando sua própria restauração para ajudar a família enlutada a seguir em frente é representado pelo modelo teórico composto pelas categorias: deparando-se com a tragédia na família, avaliando o cenário da assistência, mobilizando seus recursos internos, conduzindo o cuidado e refletindo sobre as repercussões da experiência.

Considerações finais:

O processo representa esforços empreendidos pelos estudantes na busca de sua restauração para oferecer o melhor cuidado à família, por meio de acolhimento, escuta, sensibilidade e flexibilidade, de modo a oportunizar que ela se fortaleça para planejar seu futuro.

Descritores:

Suicídio; Família; Pesar; Educação em Enfermagem; Atitude Frente à Morte

INTRODUCTION

Suicide crisis can be defined as a situation of intense emotional disturbance resulting from of an event that causes deep psychic pain to the individual(11 Botega NJ. Crise suicida: avaliação e manejo. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2015.), standing out the desire to die and making the individual to make an attempt on his/her own life. Thereby, suicide its a matter of a violence intentionally self-inflicted so the individual can end his/her own life(22 Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Prevención de la conducta suicida. Washington: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2016.), as the suicide attempt differs from suicide only in relation to outcome, which does not cause death(33 Bertolote JM, Mello-Santos C, Botega NJ. Detecting suicide risk in psychiatric emergency services. Rev Bras Psiquiatr[Internet]. 2010[cited 2016 May 17];32(2):87-95. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbp/v32s2/en_v32s2a05.pdf

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbp/v32s2/en_v3...

).

In 2012, suicide resulted in 800 thousand deaths worldwide, which represents one death every 45 seconds and a coefficient of 11.4 deaths for every 100 thousand inhabitants(44 World Health Organization-WHO. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Geneva: WHO; 2014.).

The leading coefficients of suicide are found in Eastern Europe, Asia and some countries in Africa and Latin America(11 Botega NJ. Crise suicida: avaliação e manejo. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2015.). Between 2000 and 2012, there was a 28% drop in the overall suicide mortality coefficient. However, Brazil is one of the 29 of the 172 countries listed by the World Health Organization in which an increase in this index was identified, ranking the 8th place among the countries with the greater absolute numbers of suicide deaths(44 World Health Organization-WHO. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Geneva: WHO; 2014.).

Risk factors as being male, young adults and older people, and having mental disorders, hopelessness, helplessness, family history of suicide, family instability and recent affective loss increase the likelihood of someone committing suicide(11 Botega NJ. Crise suicida: avaliação e manejo. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2015.).

On the other hand, several recent studies demonstrate that there is an inverse relation between suicidal behavior and family protection factors as support, cohesion and adaptation in the family on moments of crisis(55 Rojas IG, Saavedra JE. Cohesión familiar e ideación suicida en adolescentes de la costa peruana en el año 2006. Rev Neuropsiquiatr[Internet]. 2014[cited 2015 Dec 13];77(4):250-61. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/rnp/v77n4/a08v77n4.pdf

http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/rnp/v77n4/a...

6 Chau K, Kabuth B, Chau N. Gender and family disparities in suicide attempt and role of socioeconomic, school, and health-related difficulties in early adolescence. BioMed Res Int[Internet]. 2014[cited 2015 Dec 13];ID314521. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2014/314521/

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/20...

7 You A, Chen M, Yang S, Zhou A, Qin P. Childhood adversity, recent life stressors and suicidal behavior in chinese college students. PLoS ONE[Internet]. 2014[cited 2015 Nov 6];9(3):e86672. Available from: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0086672&type=printable

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article...

-88 Ortiz-Hernández L, Valencia-Valero RG. Disparidades en salud mental asociadas a la orientación sexual en adolescentes mexicanos. Cad Saúde Pública[Internet]. 2015[cited 2016 Sep 13];31(2):417-30. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csp/v31n2/0102-311X-csp-31-02-00417.pdf

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csp/v31n2/0102-...

), also involving suicide attempts among children constantly exposed to family conflicts that could be prevented or addressed appropriately(99 Santos RPM, Melo MCB. Tendencia suicida en niños accidentados. Psicol Ciênc Prof[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 Mar 9];36(3):571-83. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pcp/v36n3/1982-3703-pcp-36-3-0571.pdf

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pcp/v36n3/1982-...

). This signals the importance of greater preventive efforts whereas families as context of attention and care(55 Rojas IG, Saavedra JE. Cohesión familiar e ideación suicida en adolescentes de la costa peruana en el año 2006. Rev Neuropsiquiatr[Internet]. 2014[cited 2015 Dec 13];77(4):250-61. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/rnp/v77n4/a08v77n4.pdf

http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/rnp/v77n4/a...

), since this type of death causes intense mental suffering for the family, and can increase their own predisposition to suicide.

Thus, it is important to emphasize that the morbidity and mortality associated with suicidal behavior, including on the part of relatives, reflects the negative impact on public health. However, despite the Brazilian National Strategy for Suicide Prevention(1010 Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Prevenção do Suicídio: manual dirigido a profissionais da atenção básica. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2009.) recommending professional qualification for the management of the impact of the event on the family, it is noted that professionals still feel limited and insecure when dealing with this situation(1111 Moraes SM, Magrini DF, Zanetti ACG, Santos MA, Vedana KGG. Attitudes and associated factors related to suicide among nursing undergraduates. Acta Paul Enferm[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 Mar 9];29(6):643-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v29n6/en_1982-0194-ape-29-06-0643.pdf

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v29n6/en_19...

-1212 Carmona-Navarro MC, Pichardo-Martínez MC. Attitudes of nursing professionals towards suicidal behavior: influence of emotional intelligence. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem[Internet]. 2012[cited 2015 Nov 6];20(6):1161-8. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v20n6/19.pdf

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v20n6/19.p...

).

Regardless of this panorama, studies that focus on professional training in relation to care of bereaved family after the suicide of a loved one were not found to date. Specifically in relation to the experiences of nursing academics, international studies identified difficulties inherent to the interaction with the suicidal patient, as fear and lack of ability to collect information on the suicidal behavior and develop the clinical reasoning aiming to provide therapeutic interventions(1313 Scheckel MM, Nelson KA. An interpretative study of nursing students’ experiences of caring for suicidal persons. J Prof Nurs[Internet]. 2014[cited 2015 Nov 6];30(5):426-35. Available from: http://www.professionalnursing.org/article/S8755-7223(14)00061-1/pdf

http://www.professionalnursing.org/artic...

), and verified the positive influence of active teaching methods based on simulations in performance of the assessment of suicide risk(1414 Pullen JM, Gilie F, Tesar E. A descriptive study of baccalaureate nursing students’ responses to suicide prevention education. Nurs Educ Pract[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 Feb 15];16(1):104-10. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471595315001638

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/art...

-1515 Luebbert R, Popkess A. The influence of teaching method on performance of suicide assessment in baccalaureate nursing students. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc[Internet]. 2015[cited 2017 Mar 9];21(2):126-33. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1078390315580096

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1...

).

Considering the nurse’s potential to provide care to families – since that is the professional who usually spends more time with them – and pondering about the importance of adequate training of nursing academics to play such role, we emphasize the existing knowledge gap in relation to the interaction of nursing students and the family in this situation, which would allow establishing teaching/learning strategies to better prepare these students.

Thus, we question: How does the care process provided by nursing students to the bereaved families after a loss by suicide occur?

OBJECTIVE

To understand how the nursing academics experience the process of taking care of bereaved families after a suicide loss, to identify the meanings of the experience and to build a theoretical model.

METHOD

Ethical aspects

The research project was initiated only after approval by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of Botucatu, recognized by the National Committee for Ethics in Research via Plataforma Brasil (Brazil Platform).

Participants were invited personally by one of the researchers and, in compliance with the Resolution no. 466/2012 on research involving human subjects of the National Health Council(1616 Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Resolução n. 466/2012. Normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos[Internet]. 2012[cited 2017 Mar 9]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2013/res0466_12_12_2012.html

http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis...

), she clarified the study objectives and procedures, the guarantee of confidentiality, the right to anonymity, the free access to the recordings and the transcripts of interviews (being possible to add or correct information) and on the freedom to participate or not of the survey. Each participant signed an Informed Consent Form, receiving a copy this document.

Type of study and theoretical-methodological framework

This is an analytical study of qualitative approach, enlightened by the theoretical perspective of Symbolic Interactionism, whose assumption emphasizes the interactive nature of human experiences(1717 Charon JM. Symbolic interactionism: an introduction, an interpretation, an integration. 10th ed. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2010.). Therefore, the theoretical referential assisted in the understanding of the experience of nursing academics on the process of care offered to bereaved families after a suicide loss, since this involves meanings and strategies that facilitate or complicate the students’ interaction with the family.

As method, the Grounded Theory was used, which allows the simultaneous data collection an analysis. Detailed exploration of systematically gathered data generates a set of well-developed and interrelated categories to form a theoretical model able to optimize the understanding of the experience and provide guidelines for action(1818 Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.).

Methodological procedures

To ensure the rigor and credibility of the research, the checklist that forms the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) was used. It consists of 32 items that assist the description of important aspects relating to the team of researchers, the study design and the data analysis in qualitative research(1919 Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ):a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care[Internet]. 2007[cited 2015 Dec 13];19(6):349-57. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article-...

), as subsequent description.

Study scenario and data source

The study was conducted in a private higher education institution located in the inland of São Paulo, which offers, among others, the undergraduate degree in nursing with a duration of four years. In the first year of data collection, 64 students were enrolled in the 1st year, 48 students in the 2nd, 33 students in 3rd and 30 students in the 4th year of the degree.

The undergraduate nursing students that participated in the research met the following inclusion criteria: to be older than 18 years, to be enrolled in the 3rd or 4th year of the degree, and to have experienced situations of family care after the a loved one’s suicide, whether through practices performed during the curricular internships or along the extension project in the area of care to families after a suicide crisis of a loved one supported by educational institution in partnership with the Support Center for Family Health in Botucatu, a municipality with higher rates of suicide attempts compared to the national average(2020 Bertolote JM. Why is Brazil losing the race against youth suicide? Rev Bras Psiquiatr[Internet]. 2012[cited 2015 Dec 13];34(3):245-6. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbp/v34n3/v34n3a03.pdf

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbp/v34n3/v34n3...

).

All 16 students intentionally invited (ten enrolled in the 3rd year and six enrolled in the 4th year of the course), in accordance with the inclusion criteria, agreed to participate and formed the sample of the research, with six men and ten women, aged between 22 and 35 years. Eleven patients were Catholic, two Spiritist and one Buddhist. This sample was defined by the criterion of theoretical saturation, when the concepts and categories identified were better clarified and as no new data was discovered(1818 Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.).

The first sampling group consisted of nine students who had prior professional experience in the health area, i.e., worked in the area before entering the undergraduate nursing degree (seven nursing technicians, one physical therapist and one health care agent), seeking closer approach with the studied phenomenon and the formation of categories that would direct the second sampling group, formed by seven students without any previous professional experience in the health area.

Data collection and organization

Data were collected from May 2014 to April 2015 in the researched institution, in periods previous to academic activities, according to the participants’ preference. The researchers who conducted the study were doctors in the nursing area, with experience and training on the subject and methodology adopted.

Audio-recorded interviews between 25 and 50 minutes were conducted based on the trigger question: Tell me about a situation in which you had the opportunity to take care of a family after a suicide loss. How was to take care of that family for you?

Each participant was interviewed once and, after each interview, observation notes were prepared with analytical thoughts, issues to be better understood and emotional reactions of the participants.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed in full and analyzed according to the constant comparative method between categories, recommended by the Grounded Theory, seeking similarities and differences that would evidence properties and dimensions, enabling the theoretical conceptualization(1818 Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.). This method consists of three analytical steps. In the first, open coding, the transcribed text was fragmented into excerpts and examined line by line, generating codes that, grouped, formed categories and subcategories. In the second, axial coding, the categories were related to its subcategories to explain accurately and completely the phenomena. In this step, the scheme named paradigmatic model was used to organize and classify the emerging connections between categories, featuring as basic components: causal conditions, context, intervenient conditions, strategies of action/interaction and consequences. In the third step, selective coding, the theory was integrated and refined(1818 Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.). From then on, the phenomenon, represented by a central category, was identified, and the grounded theory was presented by writing a plot, in which the categories and subcategories were displayed in italics to explain the representative theoretical model of the process. The diagram that represents the theoretical model was validated by two students participating in the survey, one from each sampling group, chosen at random, and was considered significant in relation to the experience of taking care of bereaved families after the suicide of a loved one.

RESULTS

Data analysis guided by theoretical and methodological referential allowed the understanding of how the nursing academics experience the process of taking care of bereaved families after a suicide loss. The phenomenon was portrayed by the central category seeking his/her own restoration to help the bereaved family to move on and by the five interrelated categories organized according to the steps of the Grounded Theory(1818 Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.), representing the symbolic meanings of the experience: facing the tragedy in the family (cause), evaluating the caring scenario (context), mobilizing his/her internal resources (intervenient conditions), performing the care (strategies) and reflecting on the repercussions of experience (consequences).

The process of taking care of bereaved families after the suicide of a loved one involves the dynamics between the acknowledgment that the academic is facing a tragic situation, the questioning about the care offered to the family at the moment of crisis, the idealized and undertaken actions to provide the best care to the family and the considerations on the consequences of such care for the student.

In the theoretical model proposed (Figure 1) it is possible to analyze the integration between the categories and the articulation with the central category, representing the experience of nursing academics in this specific situation.

Representative diagram of the theoretical model seeking his/her own restoration to help the bereaved family to move on

Seeking his/her own restoration to help the bereaved family to move on is the apprehended phenomenon and central event in which the actions and interactions undertaken by the nursing student in the care to family are connected. During the experience of taking care of bereaved families after a suicide loss, the student feels the need to seek his/her own restoration, because he/she is also impacted by the family tragedy, only then being able to take care properly of these families.

The experience begins with the student facing the tragedy in the family, reflecting on the causes that led to the emergence of the phenomenon. At first, the student will gradually recognize the impact of suicide on the family as he/she verifies that this is, in fact, a real and definitive situation: the family lost their loved one after the suicide. Given this circumstance, the student considers that the family is shaken and it causes, in addition to intense emotional distress expressed by the loss and feeling of guilt, repercussions on the physical health of family members. By perceiving the singularities of each family in the face of tragedy, the student identifies that while some families react from the need to verbalize their suffering, others feel the desire to go through that initial moment with periods of introspection and reflection, driven by the feeling of shame due to the situation of death and the anger for losing their loved one.

In this occasion, the student will gradually feel impressed when approaching the family history. The nursing academics feels bewildered as the family relates the circumstances of the death of their loved one, as well as the means used to end the life.

The impact when approaching the family history leads the student to seek justifications for what happened and, to this end, the academic carries out his/her own judgement, seeking to identify patterns of family functioning that may be related to the tragedy. When the nursing academic identifies a family as dysfunctional, for example, by submitting inappropriate patterns of communication between their members, he/she reflects on the relation of this behavior with the suicide.

However, the student still experiences the beginning of the situation by evaluating the need to take care of the family professionally, to strengthen the potential of mutual support among its members: he/she is conscious that there was a significant loss for the family that has difficulties in accepting this tragic death. The difficulties are observed through the expression of feelings of outrage and denial in the family, identified by the student as belonging to the grieving process of the family.

By seeking his/her own restoration to help the bereaved family to move on, the student is conscious that suffered great impact not only by knowing the circumstances of suicide death, but also by evaluating the caring scenario, the hostile context in which the phenomenon of taking care of the bereaved family happens. In this regard, the student perceives that the interaction with the bereaved family occurs in a scenario marked by aggressiveness besides the suicide death itself. By perceiving the lack of a guideline for the care to the family, despite knowing that suicide attempts are an increasing phenomenon, the student observes at health services, including the emergency ones, that professionals do not know how to lead the care to family member after the death of their loved one.

The nursing academic observes the professional’s performance while still seeking, unsuccessfully, to save the life of the patient who tried to commit suicide and, recognizing that there is more concern about biological and bureaucratic aspects of health care, perceives that the clinical care to patients are prioritized. In terms of care to families, the student observes that when the professional notes their presence, the former measures the blood pressure and, if necessary, administers some antihypertensive or antidepressant, provides information regarding the release of the body to the funeral home or requests the psychiatrist’s evaluation and, in his/her understanding, this would be an opportunity to provide some kind of care, more humane and embracing, for the families.

The student still evidences a fragmented care to the family, because in the context of emergency service, he/she realizes that only the psychiatrist, when requested, is responsible for talking with the family members after the death of the loved one. In addition, the academic believes that in the context of primary health care, the professionals do not fully know the case and do not even know whether the family may need some kind of assistance.

In this caring scenario, the little approach of the healthcare team to the family is permeated by a certain aggressiveness and, bothered with the professional’s lack of sensitivity, the student presences provocative comments in relation to patients who made an attempt on his/her own life: during the clinical care carried out in the attempt to their survival, professionals suggest what patients could have done to, in fact, succeed in their desire to die. For the student, the family senses such climate of disrespect and lack of commitment to their suffering. When even after the investment maneuvers to save him/her, the patient dies, the student, feeling uncomfortable with the professionals’ attitudes, recognizes that there is not much to be done as an undergraduate student in an internship given the jocular comments and lack of consideration to the family given the loss of a loved one, the student’s only choice is to comply great embarrassment with hostile situation at the moment.

The aggressiveness that permeates the suicide death and the scenario of hostility in which the interaction with the family commonly occurs deeply impacts the student. The family tragedy provides the student the event of coming into contact with his/her own tragic experiences and, by mobilizing his/her internal resources, the nursing academic expresses his/her history, previous experiences, feelings and beliefs that work as intervenient conditions able to influence the impact on the experience of taking care of the bereaved family. This is the process component that enables the student to experience the phenomenon seeking his/her own restoration to help the bereaved family to move on.

The student still recognizes him- or herself as a suicide survivor, having experienced the loss of a family member or someone close to his/her living by this cause in the past. This experience allows an intense mental activity in which the student interacts with him- or herself, providing the opportunity of being in the position of the family that just lost a loved one, expressing fear in the face of his/her own thoughts on death and suicide and leaning on his/her religious beliefs to better understand his/her and the family’s tragedies. Given this mental activity, the student reacts by showing divergences between his/her thoughts, since that at certain times he/she condemns the suicide death and at others recognize it as a consequence of a mental illness.

When seeking his/her own restoration to help the bereaved family to move on, the student, even impacted, in response to his /her reflections, believes to be able to undertake action and interaction strategies by leading the care, regardless of coming across into barriers that may influence his/her action. By outlining the best care, despite valuing teamwork, the student points the nurse as the most qualified professional to interact with the family, due to the nurse’s skills of embracement, listening, sensitivity and flexibility and to normally being closer of the family, being able to prevent a greater suffering, which can facilitate the planning of the family life after the loss.

However, when noting the proximity of the moment to act and interact with the family, the student will gradually admit his/her personal barriers as perceiving him- or herself apprehensive at the beginning of the interaction for not knowing exactly how to act, recognizing that he/she still has not had many opportunities to take care of families in this specific situation. Nonetheless, driven by the genuine desire to help and to meet the requirements of the internship, the student behaves by taking care for the family to move on through actions which aim to strengthen them and ensure that they remain physically and mentally healthy, glimpsing a future even after the loss of their loved one. The student considers important to support the family while maintaining a relationship of trust to assist them in searching a sense for what happened and for a life after the suicide of a loved one. From then on, he/she identifies the emotional support as the primary need of the family, seeking then to act with with compassion and solidarity given their suffering.

By seeking his/her own restoration to help the bereaved family to move on, the student acknowledges the consequences of the process of taking care of bereaved families after a suicide loss and reflects on the impact of his/her experience. During the process in which the student is very close to the family tragedy, he/she will gradually elaborate ideas of horror about the tragic death in his/her thoughts, especially after providing the care, reliving the reports of the family and wondering how the death would have happened, which leaves him/her deeply anxious. Even so, the student is able to evaluate his/her performance together with the family and recognizes that, although the care could be provided, he/she would like to feel more prepared, suggesting improvements to his/her vocational training. Given the feeling of anxiety and unpreparedness, the student assumes his/her own need of care to be personally restored after this process, signaling the need for emotional, spiritual and permanent support of the professor, before, during and after this experience. It is important to highlight that only through this restoration it is possible to provide the best care to the bereaved families after a loved one’s suicide.

DISCUSSION

The theoretical model built allows to visualize the interaction between categories on a continuous basis during the process, enabling different paths for the student in his/her trajectory to take care of bereaved families after the a loved one’s suicide, depending on the changes in the context or in the current conditions. With that, the reflections on suicide death can occur after approaching the tragedy, when the student becomes acquainted with the family history. However, he/she can also reflect continuously during the whole experience.

By seeking his/her own restoration to help the bereaved family to move on, the student is conscious that he/she need to be restored, because the family tragedy brings near his/her own adversities – experiences, feelings and beliefs that make him/her feel frightened and apprehensive. From his/her point of view, the student will be able to be restored through emotional, spiritual and permanent support of the professor and believes that only in this way he/she will able to take care properly of the family, so that they can move on, although the death of their loved one.

The first impact evidenced in the experience relates not only to the fact of the student knowing the circumstances of death, but also to the family functioning perceived as inappropriate, which causes the student, internally, to blame the family for the suicide. This judgement may be justified by the fact that culturally, among all kinds of death, the suicide is the one in which the family functioning is more intensely questioned(2121 Imaz JAG. Familia, suicidio y duelo. Rev Colomb Psiquiat[Internet]. 2013[cited 2015 Feb 13];43(S1):71-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v42s1a10.pdf

http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v...

).

In fact, it is hard for the family not to feel responsible for the death of their loved one(1111 Moraes SM, Magrini DF, Zanetti ACG, Santos MA, Vedana KGG. Attitudes and associated factors related to suicide among nursing undergraduates. Acta Paul Enferm[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 Mar 9];29(6):643-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v29n6/en_1982-0194-ape-29-06-0643.pdf

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v29n6/en_19...

,2121 Imaz JAG. Familia, suicidio y duelo. Rev Colomb Psiquiat[Internet]. 2013[cited 2015 Feb 13];43(S1):71-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v42s1a10.pdf

http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v...

) and the blame is experienced in an excruciating manner, for feeling that they should have done something to prevent the death but did not(2121 Imaz JAG. Familia, suicidio y duelo. Rev Colomb Psiquiat[Internet]. 2013[cited 2015 Feb 13];43(S1):71-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v42s1a10.pdf

http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v...

). In this sense, the proper training should focus on abilities aimed at a comprehensive, safe and therapeutic approach, free from moral judgments(1111 Moraes SM, Magrini DF, Zanetti ACG, Santos MA, Vedana KGG. Attitudes and associated factors related to suicide among nursing undergraduates. Acta Paul Enferm[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 Mar 9];29(6):643-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v29n6/en_1982-0194-ape-29-06-0643.pdf

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v29n6/en_19...

,1313 Scheckel MM, Nelson KA. An interpretative study of nursing students’ experiences of caring for suicidal persons. J Prof Nurs[Internet]. 2014[cited 2015 Nov 6];30(5):426-35. Available from: http://www.professionalnursing.org/article/S8755-7223(14)00061-1/pdf

http://www.professionalnursing.org/artic...

,2222 Botti NCL, Araújo LMC, Costa EE, Machado JSA. Nursing students attitudes across the suicidal behavior. Invest Educ Enferm[Internet]. 2015[cited 2017 Mar 9];33(2):334-42. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/iee/v33n2/v33n2a16.pdf

http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/iee/v33n2/v...

).

However, when approaching the hostile caring scenario, the student is bothered with the lack of preparation and sensitivity of professionals when addressing not only the family, but the patient, in the attempt of reversing the self-inflicted injuries.

In addition, literature also states that professionals often lack interpersonal abilities and stigmatizing attitudes before suicidal crises(1212 Carmona-Navarro MC, Pichardo-Martínez MC. Attitudes of nursing professionals towards suicidal behavior: influence of emotional intelligence. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem[Internet]. 2012[cited 2015 Nov 6];20(6):1161-8. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v20n6/19.pdf

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v20n6/19.p...

). In this sense, education aimed at dealing with prejudice and the negative view surrounding the suicide in society is a fundamental tool to facilitate the knowledge on the subject(2222 Botti NCL, Araújo LMC, Costa EE, Machado JSA. Nursing students attitudes across the suicidal behavior. Invest Educ Enferm[Internet]. 2015[cited 2017 Mar 9];33(2):334-42. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/iee/v33n2/v33n2a16.pdf

http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/iee/v33n2/v...

), with the potential to transform this scenario marked by professional unpreparedness.

Another point of emphasis is the fact that the student, after intense mental activity that enables him/her to interact with his/her own self(1616 Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Resolução n. 466/2012. Normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos[Internet]. 2012[cited 2017 Mar 9]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2013/res0466_12_12_2012.html

http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis...

), identifies him- or herself with the experience of the family. It is important that the professor deals with the feelings of identification in a conscious manner, since this countertransference has important significance within the caring context, helping the student to understand the most obscure family experiences. However, if this identification is not in the conscience, it can result in destructive feelings and actions(11 Botega NJ. Crise suicida: avaliação e manejo. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2015.).

This mental activity still causes the student to face his/her own suicidal thoughts. Studies that sought to identify the suicidal conduct throughout life among students of Nutrition(2323 Perales A, Sánchez E, Parhuana A, Carrera R, Torres H. Conducta suicida en estudiantes de la escuela de nutrición de una universidad pública peruana. Rev Neuropsiquiatr[Internet]. 2013[cited 2015 Dec 15];76(4):231-5. Available from: http://www.upch.edu.pe/vrinve/dugic/revistas/index.php/RNP/article/view/1172

http://www.upch.edu.pe/vrinve/dugic/revi...

) and Nursing(2424 Leal SC, Santos JC. Suicidal behaviors, social support and reasons for living among nursing students. Nursing Educ Today[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 May 22];36:434-8. Available from: http://www.nurseeducationtoday.com/article/S0260-6917(15)00398-6/pdf

http://www.nurseeducationtoday.com/artic...

) point not only the occurrence of suicidal thoughts, but also the ideation and attempts of suicide. This signals the importance of the constant concern with the training and also with the restoration of the well-being of these future professionals, during and after the intense experience of taking care in the context of the suicidal crisis.

On the other hand, to be related to the family brings the student closer to his/her experience and makes him/her believe to be able to help them. Based on the mental activity performed, the student identifies the important abilities for action(1616 Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Resolução n. 466/2012. Normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos[Internet]. 2012[cited 2017 Mar 9]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2013/res0466_12_12_2012.html

http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis...

) and recognizes the nurse as crucial in the provision of care to the family in this situation. Studies corroborate the concept that both nurses and other health professionals can understand and help the patient and the family, provided they are properly prepared, able to listen carefully and provide support to minimize the suffering and despair of the family(1111 Moraes SM, Magrini DF, Zanetti ACG, Santos MA, Vedana KGG. Attitudes and associated factors related to suicide among nursing undergraduates. Acta Paul Enferm[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 Mar 9];29(6):643-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v29n6/en_1982-0194-ape-29-06-0643.pdf

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v29n6/en_19...

,2121 Imaz JAG. Familia, suicidio y duelo. Rev Colomb Psiquiat[Internet]. 2013[cited 2015 Feb 13];43(S1):71-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v42s1a10.pdf

http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v...

), interacting to focus the attention on the feelings and needs of the family(11 Botega NJ. Crise suicida: avaliação e manejo. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2015.).

In addition, recent studies establish that teaching the abilities for action in the suicide crisis during the academic training makes students more confident and satisfied before the possibility of offering this care(1414 Pullen JM, Gilie F, Tesar E. A descriptive study of baccalaureate nursing students’ responses to suicide prevention education. Nurs Educ Pract[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 Feb 15];16(1):104-10. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471595315001638

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/art...

-1515 Luebbert R, Popkess A. The influence of teaching method on performance of suicide assessment in baccalaureate nursing students. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc[Internet]. 2015[cited 2017 Mar 9];21(2):126-33. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1078390315580096

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1...

).

In relation to the care process, it is important to highlight that the student experiences in his/her thought the return of the tragic stories told by the family and the mental images elaborated on how the suicide death might have happened, causing anxiety for the student. It is believed that this is the greatest acknowledgment of his/her real need of repair. The ideal would be that there were the possibility to discuss and reflect on conflicts in relation to suicide with the supervision of a more experienced professional(11 Botega NJ. Crise suicida: avaliação e manejo. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2015.), in this case, the professor.

The desire of being able to help the bereaved family to move on is reinforced by the literature as an important action on the part of professionals, who must have clarity that the family as a system is greater than the sum of its members, and the mourning, when properly dealt, is able to function providing continuity to the future projects of the family(2121 Imaz JAG. Familia, suicidio y duelo. Rev Colomb Psiquiat[Internet]. 2013[cited 2015 Feb 13];43(S1):71-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v42s1a10.pdf

http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v...

).

Study limitations

We emphasize that the primary researcher worked as a professor in the institution studied, which could represent a limiting factor of the study. On the other hand, we believe that this fact has allowed, consciously, to reveal sensitivity for important issues in the data.

Contributions to the fields of nursing, health, or public policies

The study enabled the understanding of how the interaction of nursing students with the bereaved family occurs after a loved one’s suicide, pointing the importance of opportunities during the training of dealing with their own fears, insecurities and stigmata related to this specific care.

Considering the transformative potential of well-educated students, it will be possible to have better qualified professionals to support these families, preventing the complicated bereavement and, consequently, the illness by depression, post-traumatic stress and suicidal behavior among the bereaved, thereby contributing to the prevention of suicide and minimizing the negative impact of this event on public health.

Considering the role of the professor in the professional training of the nurse, new research paths can be traced in relation to the learning and teaching experiences on the subject.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

To understand the experience has enabled the development of an explanatory theory about the phenomenon seeking his/her own restoration to help the bereaved family to move on. To take care of bereaved families after a loved one’s suicide means that the student seeks the confrontation of his/her personal barriers to be able to offer the best care to the family through the embracement, listening, sensitivity and flexibility, so he/she provides the opportunity to the family to strengthen and glimpse life projects even after the loss of their loved one.

For this, it is essential that the students are carefully watched during their professional education. In addition, spaces for reflection and verbalization of emotions should be offered, since the professor can help the students to manage these emotions with appropriate support.

REFERENCES

-

1Botega NJ. Crise suicida: avaliação e manejo. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2015.

-

2Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Prevención de la conducta suicida. Washington: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2016.

-

3Bertolote JM, Mello-Santos C, Botega NJ. Detecting suicide risk in psychiatric emergency services. Rev Bras Psiquiatr[Internet]. 2010[cited 2016 May 17];32(2):87-95. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbp/v32s2/en_v32s2a05.pdf

» http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbp/v32s2/en_v32s2a05.pdf -

4World Health Organization-WHO. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

-

5Rojas IG, Saavedra JE. Cohesión familiar e ideación suicida en adolescentes de la costa peruana en el año 2006. Rev Neuropsiquiatr[Internet]. 2014[cited 2015 Dec 13];77(4):250-61. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/rnp/v77n4/a08v77n4.pdf

» http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/rnp/v77n4/a08v77n4.pdf -

6Chau K, Kabuth B, Chau N. Gender and family disparities in suicide attempt and role of socioeconomic, school, and health-related difficulties in early adolescence. BioMed Res Int[Internet]. 2014[cited 2015 Dec 13];ID314521. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2014/314521/

» https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2014/314521/ -

7You A, Chen M, Yang S, Zhou A, Qin P. Childhood adversity, recent life stressors and suicidal behavior in chinese college students. PLoS ONE[Internet]. 2014[cited 2015 Nov 6];9(3):e86672. Available from: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0086672&type=printable

» http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0086672&type=printable -

8Ortiz-Hernández L, Valencia-Valero RG. Disparidades en salud mental asociadas a la orientación sexual en adolescentes mexicanos. Cad Saúde Pública[Internet]. 2015[cited 2016 Sep 13];31(2):417-30. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csp/v31n2/0102-311X-csp-31-02-00417.pdf

» http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csp/v31n2/0102-311X-csp-31-02-00417.pdf -

9Santos RPM, Melo MCB. Tendencia suicida en niños accidentados. Psicol Ciênc Prof[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 Mar 9];36(3):571-83. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pcp/v36n3/1982-3703-pcp-36-3-0571.pdf

» http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pcp/v36n3/1982-3703-pcp-36-3-0571.pdf -

10Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Prevenção do Suicídio: manual dirigido a profissionais da atenção básica. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2009.

-

11Moraes SM, Magrini DF, Zanetti ACG, Santos MA, Vedana KGG. Attitudes and associated factors related to suicide among nursing undergraduates. Acta Paul Enferm[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 Mar 9];29(6):643-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v29n6/en_1982-0194-ape-29-06-0643.pdf

» http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v29n6/en_1982-0194-ape-29-06-0643.pdf -

12Carmona-Navarro MC, Pichardo-Martínez MC. Attitudes of nursing professionals towards suicidal behavior: influence of emotional intelligence. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem[Internet]. 2012[cited 2015 Nov 6];20(6):1161-8. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v20n6/19.pdf

» http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v20n6/19.pdf -

13Scheckel MM, Nelson KA. An interpretative study of nursing students’ experiences of caring for suicidal persons. J Prof Nurs[Internet]. 2014[cited 2015 Nov 6];30(5):426-35. Available from: http://www.professionalnursing.org/article/S8755-7223(14)00061-1/pdf

» http://www.professionalnursing.org/article/S8755-7223(14)00061-1/pdf -

14Pullen JM, Gilie F, Tesar E. A descriptive study of baccalaureate nursing students’ responses to suicide prevention education. Nurs Educ Pract[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 Feb 15];16(1):104-10. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471595315001638

» http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471595315001638 -

15Luebbert R, Popkess A. The influence of teaching method on performance of suicide assessment in baccalaureate nursing students. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc[Internet]. 2015[cited 2017 Mar 9];21(2):126-33. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1078390315580096

» http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1078390315580096 -

16Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Resolução n. 466/2012. Normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos[Internet]. 2012[cited 2017 Mar 9]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2013/res0466_12_12_2012.html

» http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2013/res0466_12_12_2012.html -

17Charon JM. Symbolic interactionism: an introduction, an interpretation, an integration. 10th ed. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2010.

-

18Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.

-

19Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ):a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care[Internet]. 2007[cited 2015 Dec 13];19(6):349-57. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

» https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 -

20Bertolote JM. Why is Brazil losing the race against youth suicide? Rev Bras Psiquiatr[Internet]. 2012[cited 2015 Dec 13];34(3):245-6. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbp/v34n3/v34n3a03.pdf

» http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbp/v34n3/v34n3a03.pdf -

21Imaz JAG. Familia, suicidio y duelo. Rev Colomb Psiquiat[Internet]. 2013[cited 2015 Feb 13];43(S1):71-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v42s1a10.pdf

» http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v42s1/v42s1a10.pdf -

22Botti NCL, Araújo LMC, Costa EE, Machado JSA. Nursing students attitudes across the suicidal behavior. Invest Educ Enferm[Internet]. 2015[cited 2017 Mar 9];33(2):334-42. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/iee/v33n2/v33n2a16.pdf

» http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/iee/v33n2/v33n2a16.pdf -

23Perales A, Sánchez E, Parhuana A, Carrera R, Torres H. Conducta suicida en estudiantes de la escuela de nutrición de una universidad pública peruana. Rev Neuropsiquiatr[Internet]. 2013[cited 2015 Dec 15];76(4):231-5. Available from: http://www.upch.edu.pe/vrinve/dugic/revistas/index.php/RNP/article/view/1172

» http://www.upch.edu.pe/vrinve/dugic/revistas/index.php/RNP/article/view/1172 -

24Leal SC, Santos JC. Suicidal behaviors, social support and reasons for living among nursing students. Nursing Educ Today[Internet]. 2016[cited 2017 May 22];36:434-8. Available from: http://www.nurseeducationtoday.com/article/S0260-6917(15)00398-6/pdf

» http://www.nurseeducationtoday.com/article/S0260-6917(15)00398-6/pdf

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

2018

History

-

Received

05 Apr 2017 -

Accepted

13 Sept 2017