Abstract

Councils acting in the Justice System in democracies have different purposes: to strengthen the independence of the judiciary and the public prosecutor’s office, to increase accountability of judges and prosecutors, or/and to improve justice management. This article analyzes the Brazilian National Council of Justice (CNJ) and the National Council of the Brazilian Public Prosecutor’s Office (CNMP), particularly regarding their purpose as instruments of accountability. The study shows that these bodies were created as instruments to increase transparency and compel judges and prosecutors to be held accountable for their actions and choices. The hypothesis tested in this research is that the two councils did not meet this expectation. The CNJ and CNMP were analyzed for their institutional design, discussing how the composition and distribution of positions at the council encourage independence of the judges and prosecutors rather than accountability. In addition, the article offers data on the councils’ decisions when accusations were presented. Finally, the analysis revealed that CNJ and CNMP are mainly composed of internal members of the Judiciary and the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and identified a lack of expressive punishment applied to judges and prosecutors. Therefore, the hypothesis that the councils do not work as instruments of accountability was confirmed.

Keywords:

judiciary; public prosecutor’s office; accountability

Resumo

Em democracias, conselhos, órgãos colegiados atuantes no Sistema de Justiça possuem diferentes finalidades: reforçar a independência do Poder Judiciário e do Ministério Público (MP), incrementar a accountability em relação a juízes e promotores e/ou aprimorar a gestão da Justiça. Este artigo analisa o Conselho Nacional de Justiça (CNJ) e o Conselho Nacional do Ministério Público (CNMP), considerando principalmente os dois primeiros aspectos. No momento da criação desses órgãos, acreditava-se que ambos seriam instrumentos para aumentar a transparência e possibilitar que juízes e promotores pudessem responder por suas ações e escolhas. Nossa hipótese é que essa expectativa não se realizou. Para testá-la, analisaremos o desenho institucional do CNMP e do CNJ, apontando como a composição e a distribuição de cargos incentivam mais a independência que a accountability e apresentaremos também dados relativos ao comportamento dos Conselhos frente às denúncias disciplinares. A conclusão é que, em virtude da composição majoritária do CNJ e do CNMP por integrantes internos do Judiciário e do MP e da atuação pouco expressiva em relação à punição de juízes e promotores, os órgãos reforçam ainda mais a expressiva independência dessas instituições no Brasil.

Palavras-chave:

judiciário; Ministério Público; accountability

Resumen

En las democracias, los consejos, órganos colegiados que operan en el sistema de justicia, tienen diferentes finalidades: fortalecer la independencia del Poder Judicial y del Ministerio Público (MP), incrementar la accountability con relación a jueces y fiscales, y/o mejorar la gestión de la justicia. Este artículo analiza el Consejo Nacional de Justicia (CNJ) y el Consejo Nacional del Ministerio Público (CNMP), considerando principalmente los primeros dos aspectos. Al momento de crear esos órganos, se creía que ambos serían instrumentos para aumentar la transparencia y permitir que jueces y fiscales pudieran responder de sus acciones y opciones. Nuestra hipótesis es que esa expectativa no se ha cumplido. Para probarla, analizaremos el diseño institucional del CNMP y del CNJ, señalando cómo la composición y distribución de cargos fomentan más la independencia que la accountability y también presentaremos datos relacionados con el comportamiento de los consejos ante denuncias disciplinarias. Nuestra conclusión es que, debido al hecho de que el CNJ y el CNMP están compuestos mayoritariamente por miembros internos del Poder Judicial y del MP y al desempeño insignificante con relación al castigo de jueces y fiscales, los órganos refuerzan aún más la significativa independencia de estas instituciones en Brasil.

Palabras clave:

Poder Judicial; Ministerio Público; accountability

1. INTRODUCTION

In a democracy, actors and agencies are held accountable for their actions by other actors and agencies, and may be punished or rewarded for their behavior. For accountability to be effective, it is necessary to have organizational autonomy and independence of the overseer in relation to the overseen. Thus, even though offices of professional responsibility play an important role in internal organization and can contribute with incentives to create institutional policy, they do not effectively operate as instruments of democratic accountability, precisely because the inspector retains ties with those to be inspected. They are, at best, agencies of internal control, or administrative accountability, that can ensure better management and diligent fulfillment of tasks, but do not necessarily imply accountability to society (Poulsen, 2009Poulsen, B. (2009). Competing traditions of governance and dilemmas of administrative accountability: the case of Denmark.Public Administration, 87 ( 1), 117-131.; Schedler, Diamond, & Plattner, 1999Schedler, A., Diamond, L. J., & Plattner, M. F. (Eds.). (1999).The self-restraining state: power and accountability in new democracies. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers.).

While several types of accountability are presented in the literature (Bovens, Goodin, & Schillmans, 2014Bovens, M., Goodin, R., & Schillmans, T. (Ed.). (2014). The Oxford handbook of public accountability. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.), the most relevant kind for democracy is the one based on transparency, independence, and instruments for sanction. When these features are in place, it is rational for those subject to oversight, based on the “law of anticipated reactions” (Bachrach & Baratz, 1962 as cited in Limongi, 2006Limongi, F. (2006). A democracia no Brasil: presidencialismo, coalizão partidária e processo decisório.Novos Estudos/Cebrap, 76, 17-41., p. 29), to strive and duly perform their functions, thus avoiding penalties and sanctions.

During Lula’s administration, in 2004, the creation of the National Council of Public Prosecutor’s Office (CNMP) and the National Council of Justice (CNJ) - entrusted, among other tasks, with overseeing and sanctioning judges and prosecutors - seemed to indicate that politicians would provide effective instruments of democratic accountability with regard to the Public Prosecutor´s Office (Ministério Público, in Portuguese) and the Judiciary. This possibility, however, was no longer so compelling at the time of that reform. It was at the heart of the debate in the 1980s and 1990s, especially during the National Constituent Assembly. But the defeat, at the time, of the attempt to introduce instruments of external control of the Justice System, as well as the debate that ensued, made it clear that what was really at stake in the reform of the Lula administration was the implementation of instruments of internal control (Fragale, 2013Fragale, R. Filho,. (2013). Conselho Nacional de Justiça: desenho institucional, construção de agenda e processo decisório. Dados, 56(4), 975-1007.; Ribeiro & Arguelhes, 2015Ribeiro, L. M., & Arguelhes, D. W. (2015). O Conselho no Tribunal: mudança institucional e a judicialização de decisões do CNJ junto ao Supremo Tribunal Federal. Revista Direito e Práxis, 6(12), 464-503.; Ribeiro & Paula, 2016Ribeiro, L. M., & Paula, C. J. (2016). Inovação institucional e resistência corporativa: o processo de institucionalização e legitimação do Conselho Nacional de Justiça. Revista Brasileira de Políticas Públicas, 6(3), 13-28.). The level of insulation of these bureaucracies, especially in regard to the Public Prosecutor´s Office, is quite high and somewhat unusual in comparison, something that has not changed with these reforms.

Our aim in this article is to assess whether these Councils met the initial expectation of becoming agencies of accountability - albeit exclusively internal - in relation to Brazilian judges and prosecutors. To this end, we shall consider both through the lens of their autonomy and composition, as well as of their effective capacity to sanction those who fail to meet their obligations.

The questions we intend to address are: do these Councils act as instruments of accountability, holding the Public Prosecutor´s Office and the Judiciary “accountable” for their actions? Hence: do these Councils serve as mechanisms to control the extensive autonomy of judges and prosecutors?

In order to address them we will consider two aspects. The first one involves an analysis of the institutional design of both the CNMP and the CNJ, which suggests that the composition and distribution of seats promote independence over accountability. The second aspect refers to the analysis of data regarding the behavior of both Councils in response to disciplinary complaints. The purpose here is to establish how effective the agencies are as an instrument of accountability, even though accountability performed by peers may be a modality that is less appealing from the point of view of democracy. This is an effort to understand the two main organs of control of the Brazilian Justice System, not only from the perspective of their composition, but above all, of their performance and some of the accomplishments. We shall demonstrate that the CNMP and the CNJ, contrary to what was originally expected, are agencies that further strengthen the insulation of Brazilian prosecutors and judges, keeping them immune to accountability.

2. COUNCILS OF JUSTICE SYSTEMS

Many democracies - among them the French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Argentinian and Brazilian ones - have an organized state institution within their structure responsible for regulating the Judiciary Power through decisions taken in a collegiate process. In different political systems, these Councils are in charge of different tasks: reinforcing the independence of judicial institutions, increasing accountability of judges and prosecutors, and/or improving the management of Justice (Finkel, 2008Finkel, J. (2008). Judicial reform as political insurance. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.; Hammergren, 2002Hammergren, L. (2002, junho). Do judicial councils further judicial reform. Lessons from Latin America (Rule of Law Series, 28). Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.; Pessanha, 2013Pessanha, C. (2013). Controle do Judiciário: o Conselho Nacional de Justiça. In L. Avritzer, N. Bignotto, F. Filgueiras, & J. Starling (Org.), Dimensões políticas da justiça (pp. 505-511). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Civilização Brasileira.; Pozas-Loyo & Ríos-Figueroa, 2010Pozas-Loyo, A., & Ríos-Figueroa, J. (2010). Enacting constitutionalism: the origins of independent judicial institutions in Latin America. Comparative Politics, 42(3), 293-311., 2010a). Garoupa and Ginsburg (2008Garoupa, N., & Ginsburg, T. (2008). Guarding the guardians: judicial councils and judicial independence (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper n. 444). Chicago, IL; University of Chicago Law School.) estimate that about 60% of all countries have such bodies and that they deal with at least one of the following tasks related to judicial institutions: i) housekeeping, i.e., issues related to budget, material resources, etc.; ii) appointment of judges; and iii) performance evaluation (promotion, discipline, removals, salaries, etc.).

Since the Judiciary is generally the least accountable branch of government, it was assumed in Brazil that the creation of a Council would be a means of reducing the democratic deficit with regard to judges. During the 1980s and 1990s, and especially during the National Constituent Assembly, the discussion about the Council was focused on the institution of an instrument of external control of the Judiciary (Fragale, 2013Fragale, R. Filho,. (2013). Conselho Nacional de Justiça: desenho institucional, construção de agenda e processo decisório. Dados, 56(4), 975-1007.; Ribeiro & Arguelhes, 2015Ribeiro, L. M., & Arguelhes, D. W. (2015). O Conselho no Tribunal: mudança institucional e a judicialização de decisões do CNJ junto ao Supremo Tribunal Federal. Revista Direito e Práxis, 6(12), 464-503.; Ribeiro & Paula, 2016). In other words, by creating an institution relatively detached from the Judiciary to monitor and/or regulate the activities and careers of judges, comprising a certain number of external members or that would stem from different instances of justice, that structure, once in place, would increase accountability and decrease the independence of judges.1 1 Just like Dahl (1982), we will use “independence” and “autonomy” as synonyms for the same political phenomenon that keeps state actors from being held accountable or makes it more difficult.

Even though the issue of accountability of judicial institutions dominated the Brazilian debate, in other Latin American countries it was the issue of independence that prevailed, which was reflected in the judicial reforms adopted by them (Finkel, 2008Finkel, J. (2008). Judicial reform as political insurance. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.), even with regard to their respective Councils, aimed at strengthening the Judiciary rather than controlling it (Hammergren, 2002Hammergren, L. (2002, junho). Do judicial councils further judicial reform. Lessons from Latin America (Rule of Law Series, 28). Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.; Pozas-Loyo & Ríos-Figueroa, 2010Pozas-Loyo, A., & Ríos-Figueroa, J. (2010). Enacting constitutionalism: the origins of independent judicial institutions in Latin America. Comparative Politics, 42(3), 293-311.a).

In response to the expectation that Councils would increase accountability, restricting the autonomy of judges, the CNJ was established in Brazil. Envisioned through Constitutional Amendment 45 (2004Emenda Constitucional n.45, de 30 de dezembro de 2004. (2004). Altera dispositivos dos arts. 5º, 36, 52, 92, 93, 95, 98, 99, 102, 103, 104, 105, 107, 109, 111, 112, 114, 115, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 134 e 168 da Constituição Federal, e acrescenta os arts. 103-A, 103B, 111-A e 130-A, e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF. Recuperado dehttp://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/Emendas/Emc/emc45.htm

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/con...

), the Council fostered the belief that it was “inducing a specific dimension of social control whose possibilities stood in contrast to the previous model of a fragmented, pulverized Judiciary” (Fragale, 2013Fragale, R. Filho,. (2013). Conselho Nacional de Justiça: desenho institucional, construção de agenda e processo decisório. Dados, 56(4), 975-1007., p. 2). According to the debate at the time, “it was precisely external control [...] that constituted the ratio essendi for the creation of both Councils”2

2

The authors also refer to the CNMP.

(Streck, Sarlet, & Clève, 2005Streck, L. L., Sarlet, I. W., & Clève, C. M.(2005). Os limites constitucionais das resoluções do Conselho Nacional de Justiça (CNJ) e do Conselho Nacional do Ministério Público (CNMP). Revista da EMESC. Recuperado de http://www.egov.ufsc.br/portal/sites/default/files/anexos/15653-15654-1-PB.pdf

http://www.egov.ufsc.br/portal/sites/def...

, p. 2), which sparked distrust among the members of the justice system, to the point that the Association of Brazilian Judges (AMB) called into question the establishment of the new organ by means of a Direct Action of Unconstitutionality (ADI). The challenge was based on considering it a

heterogeneous body within the Judiciary exercising external control, with members of other powers, thus disrespecting (a) both the principle of separation and independence of powers (b) and the federative pact, in addition to the formal unconstitutionality of part of its competence (Pessanha, 2013Pessanha, C. (2013). Controle do Judiciário: o Conselho Nacional de Justiça. In L. Avritzer, N. Bignotto, F. Filgueiras, & J. Starling (Org.), Dimensões políticas da justiça (pp. 505-511). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Civilização Brasileira., p. 509).

A majority of Supreme Court (STF) Justices ruled that the creation of the CNJ would not infringe on the independence of the judiciary as guaranteed by the Constitution. The rapporteur, Justice Cezar Peluso, stated that “the Council merely represented a change of institutional architecture, whose new configuration would allow a ‘slight opening’ of the Judiciary to society” (Fragale, 2013Fragale, R. Filho,. (2013). Conselho Nacional de Justiça: desenho institucional, construção de agenda e processo decisório. Dados, 56(4), 975-1007., p. 2, emphasis added). Nunes (2010Nunes, R. M. (2010). Politics without insurance: democratic competition and Judicial Reform in Brazil. Comparative Politics, 42(3), 313-331.) also points out that the creation of the Council, geared towards administrative supervision of the judiciary, is unlikely to threaten the decision-making independence of judges. In fact, Nunes suggests the opposite effect: a Judiciary that is more independent from pressures of all kinds, especially in its governing bodies, would be able to strengthen its own governance role, ensuring more uniform decisions throughout the judicial system. As a result, it could be of interest to the heads of the national Executive branch to promote reforms that would bolster judicial independence as well as the power of the central authorities (Nunes, 2010Nunes, R. M. (2010). Politics without insurance: democratic competition and Judicial Reform in Brazil. Comparative Politics, 42(3), 313-331.).

In line with Nunes’ argument, this STF ruling indicates that the creation of Councils composed by judges is not always primarily aimed at improving accountability. Many are created as an instrument to increase the insulation of judges, seeking to ward off the influence of party politics from the Judiciary. Based on a variety of experiences in democracies, “external accountability has emerged as a second goal of councils” (Garoupa & Ginsburg, 2008Garoupa, N., & Ginsburg, T. (2008). Guarding the guardians: judicial councils and judicial independence (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper n. 444). Chicago, IL; University of Chicago Law School., p. 9) and not as its primary focus. In other words, Councils often are geared more to independence than to accountability. The formation of such bodies actually reflects a trade-off between autonomy and accountability. Increasing one means decreasing the other.

While adequate institutions might enhance judicial independence and minimize the problems of a politicized judiciary, increasing the powers and independence enjoyed by judges risks creating the opposite problem of over-judicializing public policy (Garoupa & Ginsburg, 2008Garoupa, N., & Ginsburg, T. (2008). Guarding the guardians: judicial councils and judicial independence (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper n. 444). Chicago, IL; University of Chicago Law School., pp. 17-18).

Adopting Councils that reinforce independence and not accountability meets the normative prescription that high doses of autonomy of the Judiciary with respect to other actors would be necessary (Kerche, 2018Kerche, F., & Marona, M. (2018). O Ministério Público na Operação Lava Jato: como eles chegaram até aqui? In F. Kerche, & J. Feres Jr. (Coord.), Operação Lava Jato e a democracia brasileira (pp. 69-100). São Paulo, SP: Ed. Contracorrente.). After all, it is a “normative consensus” (Melton & Ginsburg, 2014Melton, J., & Ginsburg, T. (2014, Fall). Does de jure judicial independence really matter? (Coase-Sandor Institute for Law & Economics Working Paper No. 612). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Law School., p. 187), a “normative stereotype” (Maravall, 2003Maravall, J. M. (2003). The rule of law as a political weapon. In B. Manin, & A. Przeworski. (Ed.), Democracy and the rule of law(pp. 261-301). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press., p. 264), or a “quasi-religious concept” (Taylor, 2017Taylor, M. M. (2017). Judicial independence in Latin America. No Prelo., p. 5) that independence is necessary and essential for judges to resolve disputes (Shapiro, 2013Shapiro, M. (2013). Judicial independence: new challenges in stablished nations. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 20(1), 253-277.). The literature is virtually unanimous in stating that “independent judiciaries are better situated than their less independent counterparts to enforce constitutional rights against popular majorities and thereby correct perceived injustices” (Clark, 2011Clark. T. S. (2011). The limits of judicial independence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press., p. 264). Whereas autonomy may not be a “supreme value” - since consistency, precision, predictability and expediency of decisions are also important -, it is undeniable that it is “an important component in many definitions of judicial quality” (Melton & Ginsburg, 2014Melton, J., & Ginsburg, T. (2014, Fall). Does de jure judicial independence really matter? (Coase-Sandor Institute for Law & Economics Working Paper No. 612). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Law School., p. 190).

On the other hand, an autonomous, moderate, nonpartisan Judiciary may be sympathetic to the government of the day. According to Nunes (2010Nunes, R. M. (2010). Politics without insurance: democratic competition and Judicial Reform in Brazil. Comparative Politics, 42(3), 313-331., p. 315):

a sympathetic Judiciary is one made up of judges who are sufficiently moderate in their preferences and respectful in their attitudes toward the other branches of government [...] In multiparty systems such as in Brazil, elected officials can ensure a deferential judiciary by appointing judges who espouse the positivist legal ideology, which considers the judicial role to be an instrument for enforcing the law and not for enacting it.

Thus, if a council of the judicature can, through the administrative supervision of the Judiciary, ensure greater internal discipline and party independence, it can also guarantee that the courts do not try to replace legislators and, consequently, the government. In this case, councils (such as the Brazilian one), composed predominantly of judges, are able to do this without threatening the decision-making independence of the judicature (Nunes, p. 318).

A Council’s composition is a sensible indicator of the legislators’ real intentions. Based on the number of external and internal members of the Judiciary in the collegiate, it is possible to establish whether the body hangs more on independence or accountability: “A general assumption in the literature is that a judicial majority on the council will ensure independence” (Garoupa & Ginsburg, 2008Garoupa, N., & Ginsburg, T. (2008). Guarding the guardians: judicial councils and judicial independence (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper n. 444). Chicago, IL; University of Chicago Law School., p. 22). When a majority of its members must necessarily be chosen from among the judges themselves, there is a reduced margin for accountability.

In the case of the CNJ, made up of a majority of judges, and “envisaged as an organ of the Judiciary itself” (Lima, 2017Lima, L. G. M. (2017). As medidas de natureza disciplinar no âmbito do Conselho Nacional do Ministério Público (CNMP). Revista Jurídica Corregedoria Nacional, 3, 11-33., p. 13), different perceptions seem to discern, at best, “internal accountability” (Tomio & Robl, 2013Tomio, F. R. L., & Robl, I. N. Filho,. (2013). Accountability e independência judiciais: uma análise da competência do Conselho Nacional de Justiça (CNJ). Revista de Sociologia e Política, 21(45), 29-46., p. 29). It is also worth noting that, at first, the wording provided by Constitutional Amendment no. 45 (2004Emenda Constitucional n.45, de 30 de dezembro de 2004. (2004). Altera dispositivos dos arts. 5º, 36, 52, 92, 93, 95, 98, 99, 102, 103, 104, 105, 107, 109, 111, 112, 114, 115, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 134 e 168 da Constituição Federal, e acrescenta os arts. 103-A, 103B, 111-A e 130-A, e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF. Recuperado dehttp://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/Emendas/Emc/emc45.htm

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/con...

) stipulated that “the members of the Council shall be appointed by the President of the Republic, after the selection has been approved by an absolute majority of the Federal Senate” (Art. 103-B § 2), but a new wording, introduced by Constitutional Amendment no. 61 (2009), established that “the other members of the Council shall be appointed by the President of the Republic, after the selection has been approved by an absolute majority of the Federal Senate”. In other words, external influence over the composition of the CNJ was further diminished, restricting it to the confirmation of members who are not drawn from the upper echelons of the Judiciary, the STF and the Superior Court of Justice (STJ).3

3

We thank one of the anonymous referees for bringing this point to our attention.

Whether to ensure more independence or more accountability is an option that may vary across different Councils and is usually defined at the time of their inception. France, for example, with a tradition of stronger ties between the Judiciary and the Executive (Terquem, 1998Terquem, F. (1998). Le coup D’État Judiciaire. Paris, France: Éditions Ramsay.), has designed a Council whose composition favors accountability, precisely with the aim to increase the autonomy of judges while counterbalancing their dependence on the government. Also aiming for greater balance, Spain, with a more independent Judiciary, has a Council made up mostly of members of the parliament (Pessanha, 2014Pessanha, C. (2014). A experiência dos Conselhos de Magistratura ibero-americanos: uma análise comparativa entre Portugal, Espanha, Argentina e Brasil. In Anais do 9º Encontro da ABCP, Brasília, DF.). On the other hand, in Italy, as a consequence of the trauma of the fascist period, the 1948 Constitution insulated judges and prosecutors from party political interference, something that is also reflected in the composition of the Council, made up exclusively of judges, with independence being the primary feature (Guarnieri, 2015Guarnieri, C. (2015). The courts. In E. Jones, & G. Pasquino. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of Italian politics (pp. 120-132). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.; Sberna & Vannucci, 2013Sberna, S., & Vannucci, A. (2013). ‘It´s the politics, stupid!’. The politicization of anti-corruption in Italy. Crime Law Soc. Change, 60, 565-593.).

Changes may occur over time, driving a Council originally organized so as to reinforce independence towards a model that favors accountability. In Argentina, thanks to a reform promoted by the Cristina Kirchner administration in 2006, the composition of the Council of Judicature was rearranged to strengthen the presence of members from outside the Judiciary, while the total number of councilors decreased in a clear attempt to restrict the autonomy of judges. Thus, “the influence of the political power represented by the parliamentary majority and the executive power increased, as well as excluding the president of the National Supreme Court of Justice from the presidency of the Council of Judicature [...], as stipulated in the original design” (Pessanha, 2014Pessanha, C. (2014). A experiência dos Conselhos de Magistratura ibero-americanos: uma análise comparativa entre Portugal, Espanha, Argentina e Brasil. In Anais do 9º Encontro da ABCP, Brasília, DF., p. 9).

Notwithstanding significant differences regarding the role of judges and prosecutors, a comparable discussion to the one presented so far would also be applicable to the Councils of Public Prosecutor’s Office.4 4 We will designate all agencies in charge of criminal prosecution, regardless of the denominations they may receive in other countries, as Public Prosecutor´s Office. So much so that some Councils are in charge of both of these tasks of the Judiciary, such as those in Italy and France. But if some aspects pull them together, there are differences that stand out.

Prosecutors, unlike judges, in the vast majority of cases are subordinated to the Ministry of Justice in their countries, according to a “bureaucratic” model (Kerche, 2018Kerche, F., & Marona, M. (2018). O Ministério Público na Operação Lava Jato: como eles chegaram até aqui? In F. Kerche, & J. Feres Jr. (Coord.), Operação Lava Jato e a democracia brasileira (pp. 69-100). São Paulo, SP: Ed. Contracorrente.). There are also those directly selected by voters, such as local prosecutors in the United States. In other words, whereas in the Judiciary the rule is independence from other branches of government and, consequently, from party politics, in the case of the Prosecutor´s Office the most frequent is for prosecutors to be accountable to the government (which in turn is accountable to voters), or the prosecutors themselves who are accountable to voters. In such cases, the Prosecutor´s Office members are the gatekeepers (Aaken, Feld, & Voigt, 2010Aaken, A. V., Feld, L. P., & Voigt, S. (2010). Do independent prosecutor deter political corruption? An empirical evaluation across seventy-eight countries. American Law and Economics Review, 12(1), 204-244.) who select and prioritize, based on guidelines issued by the government, what will be judged by the Judiciary, which is usually inert and only acts when provoked. It serves as a kind of regulation of the Judiciary by politics. This task of selecting and prioritizing is typical of the Executive’s activity (Shapiro, 2013Shapiro, M. (2013). Judicial independence: new challenges in stablished nations. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 20(1), 253-277.).

Thus, prosecutors typically implement the public security policy decided by politicians, accountable to voters, or have discretion to choose their priorities, but report directly to citizens through regular elections. The relationship between government and prosecutors in the bureaucratic model, as well as between voters and prosecutors in the electoral model, is marked by difficulties inherent in the relationship between principal and agent, such as asymmetry of information. As a general rule, therefore, the Public Prosecutor´s Office is an institution of the Executive branch, although its actions are focused on the Judiciary.

There is also the model of an “autonomous” public prosecutor’s office. At least two countries adopt a system in which prosecutors are rather insulated: Brazil and Italy. The respective Councils reinforce the prosecutors’ independence from governments and citizens and not their accountability, precisely because they are constituted by a majority of members draw from the Public Prosecutor’s Office. The Italian council, composed exclusively by magistrates, and the Brazilian one, in which only two of the fourteen councilors are appointed by the Legislative, are examples of Councils that strengthen Prosecutor’s Office that are already considerably autonomous, both de facto and de jure.

In short, despite having as a common trait being a collegiate body tasked with monitoring the activities of judges and prosecutors, Councils serve different purposes. Unlike a certain “common sense” would have it, some Councils tend to reinforce the autonomy of the Judiciary and the Prosecutor’s Office, while others are part of an effort to induce political accountability of judges and prosecutors. The key to verifying towards which of these sides the balance hangs is to examine the composition of these bodies.

3. THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF THE PUBLIC PROSECUTOR’S OFFICE (CNMP)

Since the 1988 Constitution, the Brazilian Public Prosecutor’s Office has been detached from the Executive Branch and attained a high degree of autonomy, retaining some obligations and significantly expanding others. This level of autonomy is quite unusual, even in a comparative perspective.

As Arantes and Moreira (2019Arantes, R. B., & Moreira, T. M. (2019). Democracia, instituições de controle e justiça sob a ótica do pluralismo estatal. Opinião Pública, 25(1), 97-135., p. 103) point out, the Brazilian Public Prosecutor’s Office (as well as the Federal Police and Public Defenders) has been carrying out a “policy for itself”, in the same way as interest groups within society, behaving “as activists in defense of their own projects of institutional affirmation, turning to society in search of support, and pressuring other political actors to this end”, shaping what the authors call “state pluralism”. That is, actors from within the state itself, especially those with a legal career, coordinate with sectors of society and pressure other political actors to defend their interests, as if these were part of society’s general demands.

During the administrations of Lula (2003-2010) and Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016), the Public Prosecutor’s Office became even more autonomous and discretionary than what had been stipulated in 1988. Institutional innovations such as the law that enabled prosecutors to deal plea bargains (Law 12850, 2013Lei Lei n. 12.850 de 2 de agosto de 2013. (2013). Define organização criminosa e dispõe sobre a investigação criminal, os meios de obtenção da prova, infrações penais correlatas e o procedimento criminal; altera o Decreto-Lei nº 2.848, de 7 de dezembro de 1940 (Código Penal); revoga a Lei nº 9.034, de 3 de maio de 1995; e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF. Recuperado dehttp://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2013/lei/l12850.htm

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_at...

), the informal relinquishing of presidential powers so that a segment of the prosecutors themselves could choose the Head of Public Prosecutor’s Office (Procurador-Geral da República, in Portuguese), the partnership with the de facto autonomous Federal Police, the authority to handle investigations of criminal matters, and more, further removed prosecutors from accountability and allowed them to reach decisions based on criteria that were not always clear. During the Workers’ Party governments, by initiative both of the Executive and of the other branches of power, a “brand-new” and unique criminal prosecution agency was created (Kerche & Marona, 2018Kerche, F., & Marona, M. (2018). O Ministério Público na Operação Lava Jato: como eles chegaram até aqui? In F. Kerche, & J. Feres Jr. (Coord.), Operação Lava Jato e a democracia brasileira (pp. 69-100). São Paulo, SP: Ed. Contracorrente.).

Still in 2004, in what seemed to be an exception to the institutional innovations geared toward more autonomy and greater discretion, the government sponsored and approved the establishment of the National Council of Prosecutor’s Office (CNMP). The expectation of some and the fear of others was that it would operate as an institution limiting the autonomy of prosecutors (Cardoso, 2004Cardoso, C. (2004, 10 de abril). Por um Ministério Público Republicano. Folha de S. Paulo. Recuperado de https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/opiniao/fz1004200410.htm

https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/opinia...

). However, as we will show below, the result was quite another. Once again, the members of the Prosecution Service succeeded in reinforcing their independence. In the words of Arantes and Moreira (2019Arantes, R. B., & Moreira, T. M. (2019). Democracia, instituições de controle e justiça sob a ótica do pluralismo estatal. Opinião Pública, 25(1), 97-135., p. 122), “like the National Council of Justice, the CNMP has become an entity for the management of the corporation itself, for the elaboration of policies and benchmarks for its members, instead of an effective agency of external control”.

3.1 The institutional design of the CNMP

The CNMP is composed of the Head of the Brazilian Public Prosecutor’s Office (Procurador-Geral da República) and thirteen other members, nominated by the President of the Republic and approved by the Senate for a two-year term, with the possibility of reappointment. Forfeiture of office occurs only if the Senate finds the councilor guilty of a crime of responsibility or in case of a final judicial sentence for common criminal offenses. In theory, this involvement of the Executive and Legislative branches in the appointment and removal could serve as an incentive for councilors to comply with the demands of politicians. In practice, however, there is no evidence that the roles of the Presidency and of the Senate are more than simply confirm the names suggested by the organs of the justice system.

The members are distributed as follows (Enciclopédia Jurídica da PUCSP, 2017Enciclopédia Pública da PUCSP. (2017, abril). Tomo Direito Administrativo e Constitucional(Edição 1). São Paulo, SP: Conselho Nacional do Ministério Público. Recuperado dehttps://enciclopediajuridica.pucsp.br/verbete/69/edicao-1/conselho-nacional-do-ministerio-publico

https://enciclopediajuridica.pucsp.br/ve...

):

-

Four members of the Prosecutor’s Office at the federal level, ensuring representation for each of the careers (Federal Prosecutors, Labor Prosecutors, Military Prosecutors, Prosecutors of the Federal District and Territories), chosen from a triple list;

-

Three members from Prosecutor’s Offices at the state level. Triple lists are presented to the respective State Head of Prosecutor’s Office (Procurador Geral de Justiça, in Portuguese). In a meeting of the National Council of Heads of State Prosecutor’s Office (CNPG), the heads decide which ones are nominated (CNMP, 2017);

-

One judge nominated by the Supreme Court (STF) and another by the Superior Court of Justice (STJ). The Supreme Court issues an announcement to receive applications from interested parties (STF, 2017);

-

Two lawyers nominated by the Brazilian Bar Association (OAB) by means of a vote held in the Full Board (Consultor Jurídico, 2017);

-

Two citizens with “outstanding legal knowledge”, one nominated by the Senate and the other by the Federal Chamber of Deputies.

The composition of the Council, in which all councilors hold law degrees, comprises a majority of Prosecutor’s Office representatives (to a proportion of eight Prosecutor’s Office members and six from outside it), nominations from State institutions that are not subject to the electoral process (to a proportion of ten to four), representatives from institutions not directly accountable to citizens (twelve to two), and only two chosen by institutions subject to electoral scrutiny.5 5 There was an attempt to occupy the position of external councilor with a member from the Prosecutor’s Office itself. This attempt was blocked by decision of a Supreme Court Justice. Retrieved from https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/brasil/fc0408200715.htm This is an expressive indication that the CNMP could not be the organ responsible for the external accountability of the Public Prosecutor’s Office as it was first envisaged.

Even the nominations from the Chamber of Deputies and Senate are mostly focused on individuals who worked previously as advisors to the Legislative and Executive Branches. To date, only two councilors nominated by the Legislative had no time served in public administration bodies. Having ties with politicians does not disqualify any councilor, of course, but it may suggest that the selection is based on criteria other than the idea of broad representation of society.

The CNMP’s main attributions are twofold: the control of “the administrative and financial activities” of the Prosecutor’s Office and “the professional duties of its members” (Regimento Interno do CNMP, art. 2º). Although “control” is the common aspect, the first reinforces autonomy, while the second, in theory, accountability.

On the side of autonomy, the CNMP “is responsible for ensuring operational and administrative autonomy [...], and may issue regulatory acts within the scope of its competence, or recommend provisions” (Regimento Interno do CNMP, art. 2º, I).6 6 The CNMP for example, gives authorization for the budget proposed by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office be submitted to the Legislative Branch. Retrieved from http://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/justica/noticia/2018-08/mpf-aprova-reajuste-de-1638-em-salario-de-procuradores-da-republica This paves the way for rules to be established for the Public Prosecutor´s Office without undergoing the legislative process. There are several examples in which the CNMP sought to further strengthen the autonomy and discretion of prosecutors, legislating in a controversial manner as to its constitutionality. We have selected three examples that illustrate this point.

The first one concerns the introduction of the Criminal Investigation Procedure (PIC) (Resolução n. 13, 2006). With this decision, the CNMP made provision for

an administrative and inquisitorial instrument, initiated and presided over by the member of the Public Prosecutor’s Office with criminal attribution [...] [having] the purpose of ascertaining whether any criminal infringements of a public nature have occurred, serving to prepare and substantiate the decision on whether or not to file the respective criminal action (Cap. I, art. 1º).

The problem is that the constitutional text required criminal investigation procedures to be assigned to the police, rejecting the possibility, proposed by the lobby of the Prosecutor’s Office during the constitutional drafting process, of shared attribution for the investigation procedure or that it be presided over by a prosecutor. The idea would be for a division of tasks to generate a kind of “autopilot” (Sutherland, 1993Sutherland, S. L. (1993). Independent review and political accountability: should democracy be on autopilot?Optimum: The journal of Public Sector Management, 24, 23-41.) in the Justice System, whereby institutions would limit themselves in a “competitive” model (Arantes, 2011Arantes, R. B. (2011). The Federal Police and the Ministério Público. In T. Power, & M. Taylor. (Org.), Corruption and democracy in Brazil (pp. 184-217). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.): the police investigates, the prosecutor accuses, and the judge decides (Kerche, 2009Kerche, F. (2009). Virtude e limites: autonomia e atribuições do Ministério Público no Brasil. São Paulo, SP: Edusp.). The CNMP, therefore, without involving the Legislative, enacted a procedure liable to constitutional challenge - which ended up being the case - which was only settled in 2015 after a ruling by the Supreme Court (STF), acknowledging the criminal investigative competence of Prosecutors by 7 to 4 votes (STF, 2015Supremo Tribunal Federal. (2015, 14 de maio). STF fixa requisitos para atuação do Ministério Público em investigações penais. Notícias STF. Recuperado de http://www.stf.jus.br/portal/cms/verNoticiaDetalhe.asp?idConteudo=291563

http://www.stf.jus.br/portal/cms/verNoti...

).

The second example in which discretion and autonomy of the Public Prosecutor’s Office were expanded, albeit not in accordance with the decisions of the politicians, took place in 2017. The councilors decided to warrant discretion “for the Public Prosecutor’s Office to desist from criminal prosecution in exchange for the confession of suspects, in crimes without violence or serious threat [...] as long as the damage was under 20 minimum wages (R$ 19,500)” (Consultor Jurídico [Conjur], 2017). The controversy surrounding this decision is due to the fact that Brazil does not follow the “principle of opportunity” in dealing with criminal action, but that of “legality”. This principle makes it mandatory to initiate proceedings for all crimes for which there is evidence of the defendant’s guilt. The criterion of public interest is not relevant for the prosecutor’s decision (Fionda, 1995Fionda, J. (1995). Public prosecutors and discretion: a comparative study. Oxford, UK: Claredon Press.). Unlike the bureaucratic and electoral Prosecutor’s Office models, in which prosecutors have discretion precisely because they are accountable for their choices, Brazil’s independent model is designed so that the prosecutors will refer to the Judiciary all cases brought to them by the police. Besides reducing the discretion of an unaccountable actor, this procedure should emphasize the division of tasks, since police, prosecutors and judges would exercise self-control. With the decision to make the principle of legality more flexible, the CNMP secured the prosecutors’ discretion without it deriving from a legislative decision.

Another example are cases involving authorization for prosecutors to hold positions in other branches of government. According to the Constitution (art. 128, II, c), Prosecution Service members are prohibited from “exercising, even when on paid availability, any other public function, except for a teaching position”, a strong provision further reinforced in 2007, when the STF declared it was opposed to prosecutors becoming ministers, secretaries or heads of diplomatic missions. Members of the Prosecutor’s Office could only obtain a leave to hold positions within the institution itself. The issue was brought into focus when, at the end of Dilma Rousseff’s second administration in March 2016, the CNMP allowed a member of the Bahia State Prosecutor’s Office, Wellington César Lima e Silva, to become Minister of Justice, like five other cases approved by the Council (Conjur, 2016). Facing negative repercussions, unlike for the previous instances, the STF annulled the inauguration (Brígido, 2016Brígido, C. (2016, 09 de março). STF anula nomeação de Wellington César no Ministério da Justiça. O Globo. Recuperado de https://oglobo.globo.com/brasil/stf-anula-nomeacao-de-wellington-cesar-no-ministerio-da-justica-18838623

https://oglobo.globo.com/brasil/stf-anul...

), aggravating the crisis that preceded the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff.

On the side of accountability, the CNMP may “hear and acknowledge complaints” (RI, art. 2, III) from any citizen. Limited by the specificity of each State Organic Law (Lima, 2017Lima, L. G. M. (2017). As medidas de natureza disciplinar no âmbito do Conselho Nacional do Ministério Público (CNMP). Revista Jurídica Corregedoria Nacional, 3, 11-33.), the councilors may determine the displacement, paid availability or retirement with salaries, as well as “other administrative sanctions”. (RI, art. 2º, III).7 7 “These additional administrative sanctions are the ones prescribed in the State Organic Laws and in Complementary Law no. 75/1993 as the following: fine (provisioned in the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Piauí, Rio Grande do Sul, and Tocantins), admonition (...Piauí and Roraima), warning, censorship, suspension, discharge (...Minas Gerais), dismissal, termination of retirement and disposability, forfeiture of position, termination of retirement and termination of promotion or relocation (...Pará)” (Lima, 2017, p. 19). Thus, the Council becomes yet another channel, in addition to the State Disciplinary Departments, through which citizens can denounce and seek punishment for prosecutors who stray from their duties. We will discuss further the effectiveness of the Council, or lack of it, in making use of its institutional instruments.

Two instances of the CNMP are fundamental to hear complaints and make decisions about them: The Plenum and the Counselor Inspector (Corregedor, in Portuguese) who is head of the CNMP’s National Disciplinary Department (Corregedoria Nacional, in Portuguese).This Counselor Inspector may hear the “disciplinary complaint”, dismiss it, file an inquiry, forward it to an Disciplinary Department of any State Prosecutor’s Office or file a disciplinary administrative proceeding (PAD), which will be examined by the Plenum. In other words, the Counselor Inspector is a gatekeeper, who can filter and decide in a monocratic way what will be submitted to the CNMP. The other councilors, in turn, hear complaints through the CNMP’s Disciplinary Department or are directly prompted by an external complaint. This can be done through a PAD, a “recall” request, a “disciplinary process review” or a “complaint for inaction or delay” (Regimento Interno do CNMP, 2020). In general terms, the decision may be dismissal, conviction or acquittal. Flowchart 1 depicting these alternatives is shown below.

The CounselorInspector therefore plays a key role when it comes to accountability at the CNMP.8 8 The position of ombudsman to the National Council of Prosecutor’s Office (CNMP) is also in place. Elected from among the councilors for a one-year term, with the possibility of being re-elected for another term, their role is to inform citizens about the activities of the CNMPC as well as to increase transparency; the ombudsman has no instruments to impose sanctions on the prosecutors. This is a more direct and streamlined channel than the Plenum to “hear claims and complaints from any interested party regarding members of the Public Prosecutor’s Office” (Regimento Interno do CNMP, art. 18, I), to perform the role of inspection and correction of the different branches of the Prosecutor’s Office, and “to initiate administrative disciplinary proceedings” (Regimento Interno do CNMP, art. 18, VI). In addition, the Counselor Inspector may call up, ex officio, “investigative or inquisitive procedures, prior to any administrative disciplinary proceeding, underway at the Prosecutor’s Office” (Regimento Interno do CNMP, art. 18, XVII), and also “administrative disciplinary proceedings underway at the Prosecutor’s Office” (Regimento Interno do CNMP, art. 18, XVIII), both ad referendum of the Plenum.

The Counselor Inspector is elected by the Plenum for a two-year term, with no possibility of reappointment. The role of Counselor Inspector is exclusive to members of the Prosecutor’s Office, so that the key position when it comes to accountability, with high levels of discretion, may only be held by a member of the institution under inspection. Once again, there is an indication that the CNMP is rather an instrument for strengthening independence than for increasing accountability.

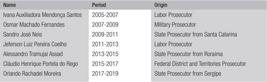

Box 2 shows the names, period of service and institutional origin of the Counselor Inspectors. It is worth mentioning that all branches of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, with the sole exceptions of the Federal Prosecutors, and the representatives of the states, have been contemplated. One possible reason is that, since the president of the CNMP is the Head of Public Prosecutor’s Office and the latter had been chosen lately by the federal prosecutors themselves,9 9 Although this is not a formal rule, governments have adhered to the Federal Prosecutor’s Office’s triple list since 2003. The practice was interrupted in 2018 by Jair Bolsonaro, who appointed Augusto Aras, someone who had not even been among the candidates to the triple list. the position of Counselor Inspector would be reserved for other branches (labor, military, Federal District and states), thus seeking some kind of internal balance.

List of names, period and origin of the Inspector General and Chief Disciplinary Counsel (CNMP)

3.2 The CNMP and the disciplinary proceedings

Another aspect for the discussion on whether the CNMP is more of an agency for accountability or for strengthening the autonomy of the Prosecutors concerns its role in handling disciplinary complaints. These may involve the behavior of a member of the Prosecutor’s Office in carrying out their duties, or a misconduct not connected to their professional activity, failure to meet deadlines, or even a request for the CNMP to call up to the federal level a disciplinary procedure initiated on a local level. The data presented by the CNMP, either in activity reports or through the Access to Information Act (LAI), do not distinguish between penalties applied to prosecutors from those applied to other Prosecutor’s Office employees.

If the CNMP is perceived by the prosecutors as a genuine instance of oversight - if not in a democratic sense, since it is practiced internally, at least in an administrative sense -, this may serve to encourage or discourage specific practices. In other words, if the Council is effective and perceived as an instrument of administrative accountability, it can shape behaviors and increase the predictability of the Prosecutor’s Office’s activity. If it is an ineffective instrument for monitoring and punishing misconduct, it will not affect prosecutors’ choices.

There is a caveat. The fact that there are few penalties can only mean that the prosecutors anticipate the CNMP’s actions, avoiding any sanctions10 10 This argument is based on the principal/agent model (Calvert, McCubbins, & Weingast, 1989). . Even though there is sufficient data showing that the punishment of a member of the Prosecutor’s Office is unlikely, the question remains: is there a low rate of punishment because the prosecutors do not make that many mistakes, or is it because the CNMP protects them? Despite the fact that sanctions are rare and lenient, the data suggest, but do not prove, the low effectiveness of the CNMP’s accountability.

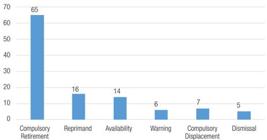

Anyway, getting a prosecutor to be sanctioned for their actions is like a hurdle race, a funnel with a narrow passage, even though the number of penalties has been growing. Between January 2010 and February 2019, more than 2,834 disciplinary proceedings reached the CNMP, which means an average of 83 per month. Between April 2007 and November 2018, the Plenum decided 509 cases, resulting in 223 penalties of different types (see Graphs 1 and 2), an average of 1.75 penalties per month. Based on the monthly average of cases and sanctions for the same period, only 2.1% of the cases result in some kind of penalty. Among them, almost half (47%) were relatively light, such as reprimand, warning or verbal admonishment. Moreover, not all penalties involve prosecutors or are related to typical prosecutorial activities.11 11 In 2016, for example, a prosecutor was punished for beating his wife and holding her in false imprisonment. Retrieved from https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2016/04/1757766-cnmp-decide-pela-demissao-de-procurador-acusado-de-agredir-a-mulher.shtml

Despite the recent increase in the number of sanctions, institutional procedures afford strong protection to Prosecutor’s Office members. Appeals and deadlines are favorable to the accused, key actors in the process are usually colleagues from within the institution - such as the Counselor Inspector, the President - and there is a high chance that the rapporteur is one of the councilors member of Public Prosecutor’s Office. In addition, while decisions at the CNMP require a majority of votes, for disciplinary matters the requirements are higher: absolute majority, regardless of the number of councilors attending the vote.

4. THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF JUSTICE (CNJ)

Brazil only created its Council of Justice in 2005. Venezuela and Peru created their own in the 1960s (Carvalho & Leitão, 2013Carvalho, E., & Leitão, N. (2013). O poder dos juízes: Supremo Tribunal Federal e o desenho institucional do Conselho Nacional de Justiça. Revista de Sociologia e Política, 21(45), 13-27.); Colombia had one in the late 1970s and several other countries created them during the 1980s and 1990s (Pozas-Loyo & Ríos-Figueroa, 2010Pozas-Loyo, A., & Ríos-Figueroa, J. (2010). Enacting constitutionalism: the origins of independent judicial institutions in Latin America. Comparative Politics, 42(3), 293-311.a). Even such a belated inception was not enough to prevent a fierce resistance from members of the Judiciary, concerned as they were about safeguarding judicial independence - perhaps even due to it. Their objection was made explicit in a survey carried out before the enactment of Constitutional Amendment 45 (2014), which indicated that, out of 738 judges, only 20% supported the participation of external members and 47% were clearly opposed. Even more revealing: 25.5% were against the very creation of a council (Sadek, 2001). These figures show that judges viewed instruments of control and accountability of the Judiciary as undesirable. Those who believed that the CNJ should still be established argued that it should be composed exclusively of judges, without external parties. The Brazilian Bar Association (OAB), on the other hand, argued for the importance of the Council (Carvalho & Leitão, 2013Carvalho, E., & Leitão, N. (2013). O poder dos juízes: Supremo Tribunal Federal e o desenho institucional do Conselho Nacional de Justiça. Revista de Sociologia e Política, 21(45), 13-27.).

Under the model adopted in Brazil, the balance was tilted towards reinforcing independence and not accountability, not only because of the overwhelming presence of internal members in the Council’s composition, but also because of the prominent role of the Supreme Court (STF). That Court is responsible for appointing members and chairing the Board (having the very President of the Court as Head of the Council). Therefore, the Supreme Court plays a leading role in the administrative and disciplinary activities of the CNJ (Carvalho, 2006Carvalho, E. (2006). O controle externo do Poder Judiciário: o Brasil e as experiências dos Conselhos de Justiça na Europa do Sul. Revista de Informação Legislativa, 43(170), 99-109.), since its President holds the power to set the agenda (Fragale, 2013Fragale, R. Filho,. (2013). Conselho Nacional de Justiça: desenho institucional, construção de agenda e processo decisório. Dados, 56(4), 975-1007.; Ribeiro & Arguelhes, 2015Ribeiro, L. M., & Arguelhes, D. W. (2015). O Conselho no Tribunal: mudança institucional e a judicialização de decisões do CNJ junto ao Supremo Tribunal Federal. Revista Direito e Práxis, 6(12), 464-503.).

4.1 Institutional design of the CNJ

The CNJ is composed of fifteen members, with a two-year term and the possibility of one reappointment. The members are appointed by the President of the Republic, after approval by the Senate. The majority is made up of members of the Judiciary itself (nine from within its ranks and six from without), nominations from state institutions that do not face electoral scrutiny (eleven from within and four from without), institutions that are not accountable to citizens (thirteen from within and two from without), and only two chosen exclusively by institutions based on citizens’ votes.

Given this composition, STF Justice Luiz Roberto Barroso stated that it would not be possible “to refer to the National Council of Justice as an external control body”, since the Judiciary “holds 3/5 of its members” and, furthermore, its decisions “may be challenged in court and the judicial decision, in this regard, will not be up to the Council, but to another judicial body [the Supreme Court]” (Barroso, 2008 as cited in Pessanha, 2014Pessanha, C. (2014). A experiência dos Conselhos de Magistratura ibero-americanos: uma análise comparativa entre Portugal, Espanha, Argentina e Brasil. In Anais do 9º Encontro da ABCP, Brasília, DF., p. 14).

All of the councilors external to the Judiciary, appointed by the Chamber of Deputies and the Federal Senate, hail from the legal world, as shown in Box 4. It is worth noting that two of the nine CNJ councilors had also been members of the CNMP. Still, two other councilors had worked in the Legislative and one in the Municipal Executive. The remainder were lawyers or law professors (one of them eventually became an STF Justice).

Beyond the initial resistance, criticism was not sparse even after the creation of the Council. In a clear display that the initiative of a more activist CNJ’s Disciplinary Department (Corregedoria Nacional de Justiça, in Portuguese) could alter the dynamics of the control agency, the Counselor Inspector (Corregedora Nacional de Justiça, in Portuguese) Eliana Calmon (2009-2012) adopted in 2011 a series of administrative measures, such as “cutting salaries above the ceiling, prohibition of nepotism, establishment of working hours in the Courts and productivity targets with transparent exposure of comparative data from state and federal courts” (Pessanha, 2014Pessanha, C. (2014). A experiência dos Conselhos de Magistratura ibero-americanos: uma análise comparativa entre Portugal, Espanha, Argentina e Brasil. In Anais do 9º Encontro da ABCP, Brasília, DF., p. 14). There were several initiatives aimed at increasing transparency and regulating issues that were basic requirements for public bureaucracies; however, they were not well received by judges. The crisis worsened when the Counselor Inspector issued the CNJ-135 Resolution in 2011, dealing with penalties for judges accused of embezzlement, in accordance with constitutional rules that grant the CNJ the power to “hear and acknowledge complaints against members or agencies of the Judiciary (...) without prejudice to the disciplinary and corrective powers of the courts” (Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil, Article 103B, #4, III, emphasis added). As Pessanha (2014Pessanha, C. (2014). A experiência dos Conselhos de Magistratura ibero-americanos: uma análise comparativa entre Portugal, Espanha, Argentina e Brasil. In Anais do 9º Encontro da ABCP, Brasília, DF., p. 14) explained, “while for some the concurrent competence of ‘CNJ and the courts’ was clear, for others, especially the professional associations, it was a subsidiary competence of the Council”. The associations’ preference was for peer review, through the internal control of their own courts, and not the CNJ, in opposition to the centralization of control powers within the Council (Ribeiro & Arguelhes, 2015Ribeiro, L. M., & Arguelhes, D. W. (2015). O Conselho no Tribunal: mudança institucional e a judicialização de decisões do CNJ junto ao Supremo Tribunal Federal. Revista Direito e Práxis, 6(12), 464-503.).

Challenging this provision, a direct action of unconstitutionality (ADI 4638) was filed by the Brazilian Association of Judges (AMB) (STF, 2012Supremo Tribunal Federal. (2012, 08 de fevereiro). STF conclui julgamento que apontou competência concorrente do CNJ para investigar juízes. Notícias STF. Recuperado de.http://www.stf.jus.br/portal/cms/verNoticiaDetalhe.asp?idConteudo=199645

http://www.stf.jus.br/portal/cms/verNoti...

). The injunction suspended the ordinance issued by the Council and the lawsuit was judged two months later, upholding the jurisdiction of the CNJ by a majority of only one vote. According to Pessanha (2014Pessanha, C. (2014). A experiência dos Conselhos de Magistratura ibero-americanos: uma análise comparativa entre Portugal, Espanha, Argentina e Brasil. In Anais do 9º Encontro da ABCP, Brasília, DF.), the decision allowed the CNJ’s Disciplinary Department to investigate judges, even when their respective courts did not initiate the process.

It is important to point out, in this case, that of the six Justices in favor of CNJ prerogatives, five were not career judges; while of the five opposing the prerogatives, four came from within Judiciary ranks. In his vote, Justice Gilmar Mendes defended the jurisdiction of the CNJ regardless of the local Disciplinary Departments of the courts: “even the stones know that the Disciplinary Departments do not work when it comes to judging their own peers” (Haidar, 2012Haidar, R. (2012). CNJ pode processar juízes antes das corregedorias. Consultor Jurídico. Recuperado dehttps://www.conjur.com.br/2012-fev-02/cnj-abrir-processos-juizes-fundamentar-decisao

https://www.conjur.com.br/2012-fev-02/cn...

). Such a decision was crucial to assure the CNJ autonomy and power for internal control of the actions and administrative activities of members of the Judiciary.

Another important decision, reached at the same session of the Supreme Court, concerned whether disciplinary problems of judges would be debated at the CNJ in open or reserved sessions. The open session was approved by 9 votes to 2. Contrary to it. Justice Luiz Fux questioned: “how can the judge perform his duties when submitted to a public trial?” (Haidar, 2012Haidar, R. (2012). CNJ pode processar juízes antes das corregedorias. Consultor Jurídico. Recuperado dehttps://www.conjur.com.br/2012-fev-02/cnj-abrir-processos-juizes-fundamentar-decisao

https://www.conjur.com.br/2012-fev-02/cn...

).

4.2 The CNJ and the disciplinary proceedings

There are four important aspects of monitoring an institution like the Judiciary: (1) transparency, (2) costs, (3) conduct of its members and (4) effectiveness in fulfilling its role. Evidently, these aspects are related, since transparency is an important instrument to monitor the other three, just as the conduct of the members will have an effect on the effectiveness of the institution as a whole. However, each of these elements is relevant in itself.

Regarding the disciplinary control of judges, between August 2016 and June 2017, the CNJ heard 7,600 cases (Conjur, 2017bConsultor Jurídico. (2017b, 28 de agosto). Corregedoria Nacional de Justiça recebeu 7,6 mil processos nos últimos 12 meses. Recuperado de https://www.conjur.com.br/2017-ago-28/corregedoria-nacional-justica-recebeu-76-mil-acoes-ano

https://www.conjur.com.br/2017-ago-28/co...

). Nevertheless, there is no assessment of the effectiveness of this type of control with regard to the sanctioning of transgressions committed by judges. A search on the CNJ website (https://www.cnj.jus.br) showed that it is possible to access information on the content of cases therein, but the search engines on the page do not enable a better structured organization of the data, by sorting the cases by date, for example, which hampers their systematization.

Through the Access to Information Act (LAI), we obtained the volume of processes and penalties applied by the CNJ in the period between 2007 and 2018. The data are presented in the Graph below. However, it is not possible to know the rank of the sanctioned official - we requested this data, but it was not provided.

Although the most serious penalty under the Organic Law of the Judicature (LOMAN) is the dismissal of the judge, it requires very specific conditions. For permanent judges, criminal prosecution for a crime is required or, in the case of an administrative proceeding, they must have performed another job in parallel, engaged in party political activity, or collected some amount of money in cases under their responsibility (Supplementary Law 35 of March 14, 1979). Non-tenured judges are also subject to dismissal for negligence, breach of decorum or incapacity to work (Supplementary Law 35, March 14, 1979). Interestingly, these are the same conditions for the most severe penalty possible for tenured judges, compulsory retirement. For this very reason, this is the most common penalty within an administrative accountability body like the CNJ.

It was imposed on 65 judges between 2006 and 2018 - in contrast to the CNMP, where compulsory retirement ranks only eighth among penalties. Of 113 cases involving punitive measures (out of a total of 153 cases in the CNJ), only five resulted in dismissal. Of the cases that did not result in a penalty, thirty were considered as unfounded, six were shelved, three resulted in acquittal, and one was declared to be time-barred.

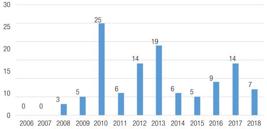

Regarding penalties per year, Eliana Calmon’s term at the head of the CNJ’s Disciplinary Department (2009-2012) marks a period of intensive action by the CNJ in terms of penalties applied. There were 50 sanctions, almost 45% of the penalties for the entire thirteen-year period of CNJ activity.

It is worth highlighting the geographical distribution of the penalties applied by the CNJ, presented in Box 5.

It is interesting to note that among the State Courts of Justice (TJs), the five states with the highest number of penalties are responsible for half of them - Alagoas (AL), Amazonas (AM), Bahia (BA), Maranhão (MA) and Mato Grosso (MT). All of them (with the exception of Bahia) are peripheral states in the Federation, apart from São Paulo (SP), which, even with the largest of the Courts of Justice (TJ), had only one penalty.12 12 Based only on this data, there is no way to establish the reasons for this difference. One could hypothesize about the work of the Disciplinary Departments in the states, which may reduce the number of cases brought to the CNJ; but the reasons may also be of a different order. Only additional research on the state Disciplinary Departments will be able to explain this.

Another issue that deserves emphasis is the response time and the possibility of enforcement of CNJ decisions in punishing abuses committed by members of the Judiciary. The delay in judging cases of abuse of power by members of the Judiciary or even penalties that are considered punishment by said members, but not by the rest of society, are aspects that further weaken the mechanisms of social control, whose institutionalization in Brazil is still incipient. A clear example of this was the CNJ’s decision to punish Judge Clarice Maria de Andrade, who retained a 15-year-old girl for 26 days in a cell holding 30 male inmates at the Abaetetuba police station, in Pará (PA), in 2007. The case was brought to trial by the CNJ in 2010, with the highest disciplinary sanction established by Organic Law of the Judicature, compulsory retirement. In an appeal to the Supreme Court, the Justices ruled that there was no evidence that the judge knew the conditions of the cell in which the teenager was held. Even so, the Supreme Court ordered the CNJ to reassess the case. It was only in October 2016 that the CNJ decided to review the judge’s penalty, removing her from the judicature for two years while keeping her salaries. After this period, the judge was allowed to resume her duties. In other words, nine years after the event, the penalty imposed was a kind of “paid leave”, deemed, however, “disproportionate” by the Brazilian Association of Judges (AMB), that came out in her defense (G1, 2016).

By comparison, there was no year in which the CNJ applied as many sanctions as the CNMP. It is worth highlighting two figures. First, in eleven years, only five dismissals have occurred - of these, four are related to the same Disciplinary Administrative Proceeding (PAD). Second, almost 45% of the cases (67 out of 155) refer to compulsory retirements, which means that the sanctioned official ceased to work but still received remuneration equivalent to their salary.

When we examine the total number of cases assigned per year at the CNJ, the figures for penalties become insignificant.

Just as it happens at the CNMP, in spite of an increase in the number of penalties over the years at the CNJ, this number is tiny when compared to the amount of cases assigned annually. The data in Graphs 4 and 5, taken together, are presented in Table 1, pointing out that less than 0.5% of the cases assigned per year result in some kind of punishment.

Both at the CNJ and at the CNMP, getting a prosecutor or a judge to be sanctioned for their actions is a rather inglorious task. For the CNJ, the annual average of penalties between 2007 and 2018 is 0.14%. In other words, very little of what reaches the Council turns into punishment. Studies that explore the (non-)penalties shall provide a more accurate understanding of what is actually sanctioned (or not), as well as the degree of (in)adequacy of the decisions. It seems unlikely, however, that only the minute proportion of less than half a percent of the complaints is actually justified.

Finally, if the creation of the National Councils of the Judiciary and the Prosecutor’s Office enhanced internal controls, democratic accountability itself remains absent. Instead of transparency, there is opacity, the Councils are mostly made up of internal members of the Judiciary and the Prosecutor’s Office. Penalties are few and far between, reinforcing not only the independence of the judicial institutions, but their insulation and the lack of accountability of their members. Such bureaucratic insulation may be interpreted as a deficiency of the control system (Cavalcante, Lotta, & Oliveira, 2018Cavalcante, P., Lotta, G., & Oliveira, V. E. (2018). Do insulamento burocrático à governança democrática: as transformações institucionais e a burocracia no Brasil. In R. Pires, G. Lotta, & V. E. Oliveira. (Eds.), Burocracia e Políticas Públicas no Brasil: intersecções analíticas (pp. 59-83). Brasília, DF: IPEA.).

5. FINAL REMARKS

Since redemocratization, Latin American countries have gone through substantial reform processes of their State institutions, in some cases by means of new constitutions, in others by transforming existing constitutional norms or by enacting infra-constitutional legislation. Among the many important changes is the transformation of judicial institutions and the creation of justice councils (Hammergren, 2002Hammergren, L. (2002, junho). Do judicial councils further judicial reform. Lessons from Latin America (Rule of Law Series, 28). Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.; Pozas-Loyo & Ríos-Figueroa, 2010Pozas-Loyo, A., & Ríos-Figueroa, J. (2010). Enacting constitutionalism: the origins of independent judicial institutions in Latin America. Comparative Politics, 42(3), 293-311., 2010aPozas-Loyo, A., & Ríos-Figueroa, J. (2010a). The politics of amendment processes: Supreme Court influence in the design of Judicial Councils. Texas Law Review, 89(1), 1807-1833.). This redesign, which resulted in the creation of new agencies, was motivated by a number of factors, such as giving greater independence to judicial actors, empowering them (Finkel, 2008Finkel, J. (2008). Judicial reform as political insurance. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.), improving the process of selecting judges (Hammergren, 2002Hammergren, L. (2002, junho). Do judicial councils further judicial reform. Lessons from Latin America (Rule of Law Series, 28). Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.), or creating more effective mechanisms for supervision and control of judges by the supreme courts (Pozas-Loyo & Ríos-Figueroa, 2010aPozas-Loyo, A., & Ríos-Figueroa, J. (2010a). The politics of amendment processes: Supreme Court influence in the design of Judicial Councils. Texas Law Review, 89(1), 1807-1833.).

In the Brazilian case, two issues have been discussed jointly: strengthening the independence of judicial institutions and creating instruments for their accountability. The institutional reinforcement and the gain of independence of the Judiciary and the Prosecutor’s Office (particularly the latter) evolved since the mid-1980s, with particular momentum during the Constituent Assembly, when new judicial structures were created, such as the Superior Court of Justice, and the Prosecutor’s Office was transformed into a kind of “fourth branch” of government (Arantes, 2011Arantes, R. B. (2011). The Federal Police and the Ministério Público. In T. Power, & M. Taylor. (Org.), Corruption and democracy in Brazil (pp. 184-217). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.; Arantes & Moreira, 2019; Kerche, 2009Kerche, F. (2009). Virtude e limites: autonomia e atribuições do Ministério Público no Brasil. São Paulo, SP: Edusp., 2014Kerche, F. (2014). O Ministério Público no Brasil: relevância, características e uma agenda para o futuro. Revista USP, 101, 113-120., 2018Kerche, F. (2018). Independência, Poder Judiciário e Ministério Público. Caderno CRH, 31(84), 567-580.). Yet, whereas the issue of accountability of judicial actors had already emerged at the time of the Constituent Assembly, its institutionalization did not thrive then, due to the ability of these stakeholders to empower themselves instead of allowing the creation of instruments for controlling them, either internally or - most notably - through some form of external control (Fragale, 2013Fragale, R. Filho,. (2013). Conselho Nacional de Justiça: desenho institucional, construção de agenda e processo decisório. Dados, 56(4), 975-1007.; Nunes, 2010Nunes, R. M. (2010). Politics without insurance: democratic competition and Judicial Reform in Brazil. Comparative Politics, 42(3), 313-331.; Ribeiro & Arguelhes, 2015Ribeiro, L. M., & Arguelhes, D. W. (2015). O Conselho no Tribunal: mudança institucional e a judicialização de decisões do CNJ junto ao Supremo Tribunal Federal. Revista Direito e Práxis, 6(12), 464-503.; Ribeiro & Paula, 2016Ribeiro, L. M., & Paula, C. J. (2016). Inovação institucional e resistência corporativa: o processo de institucionalização e legitimação do Conselho Nacional de Justiça. Revista Brasileira de Políticas Públicas, 6(3), 13-28.).

Nevertheless, the discussion about external control of judicial institutions remained heated and prompted some to hope that it could emerge from the reform of the Judiciary promoted by the Lula administration in 2004. Once again it did not happen, although two councils for the internal control of judges and prosecutors - the CNJ and the CNMP - were instituted with this reform by Constitutional Amendment 45 (2014). While some still hoped that these councils could be effective instruments of democratic accountability - that is, of some kind of external control of judicial actors -, the expectation was not fulfilled. The reform embraced much of what had already been discussed in an earlier period and the possible compromise was around instruments of administrative accountability - i.e., internal control (Fragale, 2013Fragale, R. Filho,. (2013). Conselho Nacional de Justiça: desenho institucional, construção de agenda e processo decisório. Dados, 56(4), 975-1007.; Ribeiro & Paula, 2016Ribeiro, L. M., & Paula, C. J. (2016). Inovação institucional e resistência corporativa: o processo de institucionalização e legitimação do Conselho Nacional de Justiça. Revista Brasileira de Políticas Públicas, 6(3), 13-28.; Ribeiro & Arguelhes, 2015).

It is worth noting that there was an important role of the Supreme Court in defining the real powers and competencies of the Councils when it ruled on the CNJ case. In a way, as Arantes and Moreira (2019Arantes, R. B., & Moreira, T. M. (2019). Democracia, instituições de controle e justiça sob a ótica do pluralismo estatal. Opinião Pública, 25(1), 97-135.) observe, it was not the legislator, but the Court that defined the boundaries of an agency of the justice system - in this case, its own internal control agency. In other words, the limits of control over judicial actors were stipulated by themselves - and not by democratically legitimized external agents such as the National Congress.