ABSTRACT

Context:

violence against women is present in the most diverse social groups, especially in Latin America, as it is one of the most violent regions against women, with high numbers of rapes, harassments, and murders because of gender.

Objective:

the objective of this study is to deepen the understanding of the way in which violent situations against women occurs in the Brazilian university context and its different facets of objectification and commodification.

Methods:

we undertook in-depth interviews with 15 female and 5 male university students from business courses.

Results:

our findings suggest the female ample objectification and commodification in the university context and their negative consequences, such as self-objectification in its personal and professional aspects demonstrated by reports of uncertainty regarding their bodies, in exercising the activities of leadership, and their choice of profession. There happens to be commodification of: (a) the women’s body; (b) their sexuality; (c) their morality; and finally (d) their feelings.

Conclusion:

we contribute theoretically to expand the knowledge about the relation between objectification and commodification. In empirical and managerial terms, we present insights for educational institutions to combat discrimination against women.

Keywords:

objectification; commodification; gender; woman

RESUMO

Contexto:

a violência contra a mulher está presente nos mais diversos grupos sociais, especialmente na América Latina, por ser uma das regiões mais violentas contra a mulher, com alto número de estupros, assédios e assassinatos por causa do gênero.

Objetivo:

o objetivo deste estudo é aprofundar o entendimento sobre a maneira pela qual situações violentas contra as mulheres ocorrem no contexto universitário brasileiro e as diferentes facetas da objetificação e da comodificação.

Método:

realizamos entrevistas em profundidade com 15 moças e 5 rapazes estudantes universitários de cursos de Administração.

Resultados:

nossos achados sugerem a ampla objetificação e comodificação da mulher no contexto universitário e suas consequências negativas, como a auto-objetificação em seus aspectos pessoais e profissionais, demonstradas por relatos de incerteza em relação ao seu corpo, no exercício das atividades de liderança e na escolha de profissão. Ocorre a comodificação: (a) do corpo da mulher; (b) de sua sexualidade; (c) de sua moralidade; e finalmente (b) de seus sentimentos.

Conclusão:

contribuímos teoricamente para expandir o conhecimento da relação entre objetificação e comodificação. Em termos empíricos e gerenciais, apresentamos insights para instituições educacionais combaterem a discriminação contra a mulher.

Palavras-chave:

objetificação; comodificação; gênero; mulher

INTRODUCTION

Slavery is an extreme example of the human beings totally losing their freedom and autonomy to the detriment of interests alien to their will (Hirschman & Hill, 1999Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (1999). On human commoditization: A model based upon African-American slavery. In Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 26 pp. 394-398). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.). The theory of objectification argues that an objectified human being is seen as a singular object - with differentiation - or as a common object - with little differentiation (Kopytoff, 1986Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process. In The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edit by Arjun Appadurai (pp. 64-92). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.; Belk, Wallendorf, & Sherry, 1989Belk, R. W., Wallendorf, M., & Sherry Jr, J. F. (1989). The sacred and the profane in consumer behavior: Theodicy on the odyssey. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(1), 1-38. https://doi.org/10.1086/209191

https://doi.org/10.1086/209191...

; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997....

). A common object is a kind of commodity, that is to say, an object with little differentiation (Kopytoff, 1986Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process. In The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edit by Arjun Appadurai (pp. 64-92). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.) and with value of use, sale and/or exchange (Williams, 2002Williams, C. C. (2002). A critical evaluation of the commodification thesis. The Sociological Review, 50(4), 525-542. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2286998

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?...

), and the act of transforming parts of the body of a person (and their attributes) into a commodity is denominated the commodification of people (Hirschman & Hill, 1999Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (1999). On human commoditization: A model based upon African-American slavery. In Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 26 pp. 394-398). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research./2000Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (2000). On human commoditization and resistance: A model based upon Buchenwald concentration camp. Psychology& Marketing, 17(6), 469-491. http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200006)17:6%3C469::AID-MAR3%3E3.0.CO;2-3

http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(2...

; Van Binsbergen & Geschiere, 2005Van Binsbergen, W. M., & Geschiere, P. (Eds.). (2005). Commodification: Things, agency, and identities: (The social life of things revisited) (Vol. 8). Münster: LIT Verlag.).

We have taken as our main object of study young women university students, experiencing growth in self-consciousness and concerned with their self-image. Slater and Tiggermann (2002)Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2002). A test of objectification theory in adolescent girls. Sex Roles, 46(9-10), 343-349. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020232714705

http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020232714705...

adopted Fredrickson and Roberts’ (1997)Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997....

theory of objectification and evidenced that young women face serious consequences arising from the objectification of their bodies (anxiety about their appearance and shame regarding own bodies). Girls often demonstrate excessive concern with their physical appearance and the quest for a perfect body, leading to an increase in the number of feminine plastic surgeries, silicone implants, and intimate surgical operations (Sharp, 2000Sharp, L. A. (2000). The commodification of the body and its parts. Annual Review of Anthropology, 29(1), 287-328. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.287

http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29...

; Hartsock, 2004Hartsock, N. C. M. (2004). Women and/as Commodities: a brief meditation. Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cashiers De La Femme, 23(3-4), 14-17. Retrieved from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1009.3518&rep=rep1&type=pdf

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/dow...

). These evidences were the motive for the construction of this article and the focus on young women such as women university students. It is noteworthy that authors such as Azevedo (2016)Azevedo, L. H. (2016). Gênero, violência e universidade. In C. M. Cardoso (Org.). Universidade, poder e direitos humanos (1st ed, p. 117-140). São Paulo: Cultura Acadêmica., Bandeira (2017)Bandeira, L. M. (2017). Trotes, assédios e violência sexual nos campi universitários no Brasil. Revista Gênero, 17(2), 49-79. https://doi.org/10.22409/rg.v17i2.942

https://doi.org/10.22409/rg.v17i2.942...

, Godinho, Trajano, Medeiros, Catrib, & Abdon (2018)Godinho, C. C. P. S., Trajano, S. S., Souza, C. V., Medeiros, N. T., Catrib, A. M. F., & Abdon, A. P. V. (2018). A violência no ambiente universitário. Revista Brasileira em Promoção da Saúde, 31(4), 1-8. http://doi.org/10.5020/18061230.2018.8768

http://doi.org/10.5020/18061230.2018.876...

, Linhares and Laurenti (2018)Linhares, Y., & Laurenti, C. (2018). Uma análise de relatos verbais de alunas sobre situações de assédio sexual no contexto universitário. Perspectivas em Análise do Comportamento, 9(2), 234-247. https://doi.org/10.18761/PAC.2018.n2.08

https://doi.org/10.18761/PAC.2018.n2.08...

, and Martin (2016)Martin, P. Y. (2016). The rape prone culture of academic contexts: Fraternities and athletics. Gender & Society, 30(1), 30-43. http://doi.org/10.1177/0891243215612708

http://doi.org/10.1177/0891243215612708...

argue about the need for more studies that address gender issues in the university context.

Within the state of the art on objectification of women, we note that a number of factors, on a global scale, were responsible for the increase in interest and the amount of research on this topic in scientific studies. Among these factors, we can highlight a greater reflection and social awareness regarding the patriarchal culture present in several countries (Holanda, 2015Holanda, S.B. (2015). Raízes do Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.), the sexualization of women in the pornographic industry, in advertisements, and in media in general (Gill, 2008Gill, R. (2008). Empowerment/sexism: Figuring female sexual agency in contemporary advertising. Feminism & Psychology, 18(1), 35-60. http://doi.org/10.1177/0959353507084950

http://doi.org/10.1177/0959353507084950...

), and the exponential increase in plastic surgery resulting from the idealization of a supposed female perfect body (Sharp, 2000Sharp, L. A. (2000). The commodification of the body and its parts. Annual Review of Anthropology, 29(1), 287-328. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.287

http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29...

). As a result of these and other factors, the first articles on the theme were intended to investigate the possible causes of dissatisfaction, depression, eating disorders, sexual dysfunction, anxiety, and shame of women about their own bodies. This was the purpose of the study by Fredrickson and Roberts (1997)Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997....

, which stimulated the discussion about the term ‘objectification of women’.

Beyond the objectification, women’s bodies can also be commodified in various contexts, as, for example, when a man pays for sexual services (prostitution or pornography); he is making a sexual commodity of that woman’s body (Dworkin, 1981Dworkin, A. (1981). Men possessing women. New York: Perigee.; Hirschman, 1991Hirschman, E. C. (1991). Exploring the dark side of consumer behavior: Methaphor and ideology in prostitution and pornography. In J. A. Costa (Ed.), GCB - Gender and consumer behavior (vol. 1, pp. 303-314). Salt Lake, UT: Association for Consumer Research.; Hirschman & Stern, 1994Hirschman, E. C., & Stern, B. B. (1994). Women as commodities: prostitution as depicted in the blue angel, pretty baby, and pretty woman (Vol. 21, pp. 576-581). Lancaster: ACR North American Advances.). Feminine sexuality, together with the feminine body, is greatly commodified in films, advertisements, internet pages, strip-tease clubs, sexual telephone services, sexual therapies, sex-shops, swing clubs, and night clubs in general (Carter, 1978Carter, A. (1978). The Sadeian Woman: And the ideology of pornography. New York: Pantheon Books; Dworkin, 1981Dworkin, A. (1981). Men possessing women. New York: Perigee.; Hirschman & Stern, 1994Hirschman, E. C., & Stern, B. B. (1994). Women as commodities: prostitution as depicted in the blue angel, pretty baby, and pretty woman (Vol. 21, pp. 576-581). Lancaster: ACR North American Advances.; Henriot, 2012Henriot, C. (2012). Supplying female bodies: Labor migration, sex work, and the commoditization of women in colonial Indochina and contempory Vietnam. Journal of Vietnamese Studies, 7(1), 1-9. Http://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2012.7.1.1

Http://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2012.7.1.1...

; Szymanski, Moffitt, & Carr, 2011Szymanski, D. M., Moffitt, L. B., & Carr, E. R. (2011). Sexual objectification of women: Advances to theory and research 1ψ7. The Counseling Psychologist, 39(1), 6-38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000010378402

https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000010378402...

). Commodified women are not valued for their human characteristics, so their health, physical integrity, and well-being also lose their importance (Dworkin, 1981Dworkin, A. (1981). Men possessing women. New York: Perigee.; Nussbaum, 1999Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.; Moore, 2008Moore, A. R. (2008). Types of violence against women and factors influencing intimate partner violence in Togo (West Africa). Journal of Family Violence, 23(8), 777-783. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9203-6

http://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9203-6...

; Rubini, Roncarati, Ravenna, Albarello, Moscatelli, & Semin, 2017Rubini, M., Roncarati, A., Ravenna, M., Albarello, F., Moscatelli, S., & Semin, G. R. (2017). Denying psychological properties of girls and prostitutes: The role of verbal insults. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 36(2), 226-240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X16645835

https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X16645835...

), which opens the way for the violation and violence practiced against woman.

Violence against women is present in the most diverse social groups, especially in Latin America, as it is one of the most violent regions against women, with high numbers of rapes, harassments, and murders because of gender (United Nations, 2017United Nations. (2017). From commitment to action: Policies to end violence against women in Latin America and the Caribbean. Retrieved from: http://www.latinamerica.undp.org/content/rblac/es/home/library/womens_empowerment/del-compromiso-a-la-accion--politicas-para-erradicar-la-violenci.html

http://www.latinamerica.undp.org/content...

). According to the Brazilian Public Security Forum (Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, 2019Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública. (2019). Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública. Retrieved from: http://www.forumseguranca.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Anuario-2019-FINAL-v3.pdf.

http://www.forumseguranca.org.br/wp-cont...

), in 2018 were registered 4,107 cases of homicides of women in Brazil, and 66,041 occurrences of rapes of women. About 70% of the victims are children and adolescents and it is estimated that for every ten cases, nine have as aggressors men close to the victim, such as parents, stepparents, boyfriends, or friends.

Within this empirical and theoretical context, this article’s objective is to understand in what way violent situations against women in the Brazilian university context in Administration courses demonstrate the different facets of objectification and commodification. Thus, we advance beyond the work of Hirschman and Hill (1999Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (1999). On human commoditization: A model based upon African-American slavery. In Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 26 pp. 394-398). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research./2000)Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (2000). On human commoditization and resistance: A model based upon Buchenwald concentration camp. Psychology& Marketing, 17(6), 469-491. http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200006)17:6%3C469::AID-MAR3%3E3.0.CO;2-3

http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(2...

, who deal with the process of the commodification of people, and the work of Sharp (2000)Sharp, L. A. (2000). The commodification of the body and its parts. Annual Review of Anthropology, 29(1), 287-328. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.287

http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29...

, who defends the relation between objectification and commodification.

This article’s approach has the purpose of corresponding to the existing gaps in research. Existing studies deal with the phenomenon of objectification and commodification as separate concepts and do not examine the relationship between them sufficiently (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997....

; Hirschman & Hill, 1999Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (1999). On human commoditization: A model based upon African-American slavery. In Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 26 pp. 394-398). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research., 2000Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (2000). On human commoditization and resistance: A model based upon Buchenwald concentration camp. Psychology& Marketing, 17(6), 469-491. http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200006)17:6%3C469::AID-MAR3%3E3.0.CO;2-3

http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(2...

; Haslam, 2006Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252-264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr100...

). Sharp (2000)Sharp, L. A. (2000). The commodification of the body and its parts. Annual Review of Anthropology, 29(1), 287-328. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.287

http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29...

argues that there is a relationship between the concepts and defends the idea that commodification is related to objectification in some way because it transforms people and their bodies into the objects of economic desire. He argues that if people are objectified it is possible that they have also been commodified, as in slavery, when the ownership of a slave leads to his/her being interchangeable with other objects, a characteristic of commodification (Nussbaum, 1999Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.). Thus, the biggest gap that we perceive in this literature lies in the low number of studies that relate objectification with the commodification of women.

In drawing attention to these gaps left by the literature, we contribute to the discussion of objectification when we analyze it as a process which can lead to the commodification of people, and how this is reflected in human relations (Sharp, 2000Sharp, L. A. (2000). The commodification of the body and its parts. Annual Review of Anthropology, 29(1), 287-328. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.287

http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29...

). Additionally, we identified four ways that women may be commodified in the university context of Administration courses, by: (a) commodification of the body; (b) commodification of sexuality; (c) commodification of morality; and finally (d) commodification of feelings. With our findings, we contribute directly to the theories of objectification and commodification, especially through the exposition that the objectification process of women, in different contexts, can lead to their commodification. The empirical data in our article pointed in this direction.

In empirical and managerial terms, we present contributions for teaching institutions and other organizations which combat discriminatory, controlling practices, and encourage their reflection on the humanization of women. We understand that the objectifying and commodifying behavior arising from some university students of business courses is an institutional and social problem, which can be perpetuated and generate negative effects on the labor market, compromising the results and the organizational climate, especially when it comes to the future managerial decision-makers.

We also contribute to women’s self-perception, which should also be capable of perceiving (and acting against) abuses resulting from the objectification and commodification of the woman’s body, sexuality, morality, and feelings, elements dealt with on the basis of 20 in-depth interviews and documents including reports of young Brazilian university students.

We emphasize that both discussions about gender and research on objectification of individuals are present in the literature in Administration. As an example in the Brazilian context, the National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Administration (Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação de Pesquisa em Administração [ANPAD], 2020Associação Nacional de Pós-graduação de Pesquisa em Administração. (2020). Organizational Studies Division. Retrieved from: http://www.anpad.org.br/eventos.php?cod_evento=1&cod_evento_edicao=106&cod_edicao_subsecao=1692

http://www.anpad.org.br/eventos.php?cod_...

) classifies these themes especially in the academic division of Organizational Studies, on topics such as Differences and Inequalities: Intersectionalities of Races, Ethnicities, Genders, Sexualities and Classes in the World of Work; Crime and Organizational Violence and; Ways of Resistance in Organizing Practices in Everyday Life.

In the international context, a similar classification has been adopted by the Academy of Management (Academy of Management, 2020Academy of Management. (2020). Divisions & Interest Groups. Retrieved from: http://aom.org/FAQs/Membership/What-are-Divisions---Interest-Groups.aspx.

http://aom.org/FAQs/Membership/What-are-...

), which has also associated these themes especially with discussions on Organizational Studies in the field of Administration. In addition to the sphere of organizational studies, these themes have been recurring internationally in Marketing discussions, especially in the Consumer Behavior track (Hirschman & Hill, 2000Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (2000). On human commoditization and resistance: A model based upon Buchenwald concentration camp. Psychology& Marketing, 17(6), 469-491. http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200006)17:6%3C469::AID-MAR3%3E3.0.CO;2-3

http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(2...

; Hartsock, 2004Hartsock, N. C. M. (2004). Women and/as Commodities: a brief meditation. Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cashiers De La Femme, 23(3-4), 14-17. Retrieved from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1009.3518&rep=rep1&type=pdf

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/dow...

; Max, Rice, Finkelstein, Bardwell, & Leadbetter, 2004Max, W., Rice, D. P., Finkelstein, E., Bardwell, R. A., & Leadbetter, S. (2004). The economic toll of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Violence and Victims, 19(3), 259-272. http://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.19.3.259.65767

http://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.19.3.259.657...

).

THEORIES OF THE OBJECTIFICATION AND COMMODIFICATION OF WOMEN

The act of transforming a human being into an object for the satisfaction of somebody else’s desire is called objectification (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997....

). For Haslanger (2012)Haslanger, S. (2012). On being objective and being objectified (pp. 35-39). In Resisting reality: Social construction and social critique. Oxford University Press., objectification is taken to be a relationship of domination in which the objectifier imposes his will to the detriment of someone else’s desire. Objectified people lose their human values and characteristics, thus being transported into the universe of things (Haslam, 2006Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252-264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr100...

; Morris, Goldenberg, & Boyd, 2018Morris, K. L., Goldenberg, J., & Boyd, P. (2018). Women as animals, women as objects: Evidence for two forms of objectification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(9), 1302-1314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218765739.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218765739...

). Human characteristics such as emotional responsiveness, interpersonal warmth, cognitive openness, and individuality are replaced by inertia, frigidity, passivity, superficiality and, consequently, their body can be treated as something which can be broken, violated, hurt, just like an object (Nussbaum, 1999Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.; Haslam, 2006Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252-264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr100...

). Dehumanization not only occurs in situations of conflict or of extreme negative evaluation, “dehumanization becomes a daily social phenomenon, rooted in common sociocognitive processes” (Haslam, 2006Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252-264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr100...

, p. 252).

Studies which have analyzed the consequences of objectification, specifically in the case of women, reveal that when their appearance becomes the focus, they auto-objectify themselves (Nussbaum, 1999Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997....

; Fredrickson & Harrison, 2005Fredrickson, B. L., & Harrison, K. (2005). Throwing like a girl: Self-objectification predicts adolescent girls’ motor performance. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 29, 79-101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723504269878

https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723504269878...

; Gervais, Vescio, & Allen, 2011Gervais, S. J., Vescio, T. K., & Allen, J. (2011). When what you see is what you get: The consequences of the objectifying gaze for women and men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 5-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310386121

https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310386121...

, Saguy, Quinn, Dovidio, & Pratto, 2010Saguy, T., Quinn, D. M., Dovidio, J. F., & Pratto, F. (2010). Interacting like a body: Objectification can lead women to narrow their presence in social interactions. Psychological Science, 21(2), 178-182. http://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609357751

http://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609357751...

).

In her self-objectification, a woman may diminish her competence, her qualities as an agent, the singularity of her talents, alter her perception as an individual human-being (dehumanization), devalue the importance of her feelings and experiences, and reduce her concern with physical or emotional damage - to exemplify, in a study undertaken by Heflick & Goldenberg (2014)Heflick, N. A., & Goldenberg, J. L. (2014). Seeing eye to body: The literal objectification of women. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(3), 225-229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414531599

https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414531599...

, the women behaved consistently as objects, restricting their eating and movements. Objectified women may assess themselves on the basis of their appearance, see themselves as less competent, and, consequently, undertake activities with weaker motivation and performance (Fredrickson, Roberts, Noll, Quinn, & Twenge, 1998Fredrickson, B. L., Roberts, T. A., Noll, S. M., Quinn, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (1998). That swimsuit becomes you: sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 269-284. http://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.75.1.269.

http://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.75.1.2...

; Gapinski, Brownell, & LaFrance, 2003Gapinski, K. D., Brownell, K. D., & LaFrance, M. (2003). Body objectification and fat talk: Effects on emotion, motivation, and cognitive performance. Sex Roles, 48(9-10), 377-388. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023516209973

http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023516209973...

; Quinn, Kallen, Twenge, & Fredrickson, 2006Quinn, D. M., Kallen, R. W., Twenge, J. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2006). The disruptive effect of self-objectification on performance. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(1), 59-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00262.x

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006...

; Gervais, Vescio, & Allen, 2011Gervais, S. J., Vescio, T. K., & Allen, J. (2011). When what you see is what you get: The consequences of the objectifying gaze for women and men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 5-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310386121

https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310386121...

).

There are various ways a woman may be objectified. One manifestation of objectification, seen as a simple, subtle, very common male gesture is the glance at or visual inspection of a woman’s body, when her body is treated as an object to attract, incite, or satisfy somebody’s sexual desire (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997....

). Beyond becoming someone’s property, the woman’s body can be exchanged or used in activities varying from advertising to pornography, from ‘booth babes’ (advertising models) to the traffic of human beings and sexual slavery (Henriot, 2012Henriot, C. (2012). Supplying female bodies: Labor migration, sex work, and the commoditization of women in colonial Indochina and contempory Vietnam. Journal of Vietnamese Studies, 7(1), 1-9. Http://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2012.7.1.1

Http://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2012.7.1.1...

). By way of example, pornography is a way of dehumanizing and objectifying women by removing their full moral condition and making objects of them for the satisfaction of someone’s desire (Hirschman, 1991Hirschman, E. C. (1991). Exploring the dark side of consumer behavior: Methaphor and ideology in prostitution and pornography. In J. A. Costa (Ed.), GCB - Gender and consumer behavior (vol. 1, pp. 303-314). Salt Lake, UT: Association for Consumer Research.; Haslam, 2006Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252-264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr100...

; Puvia & Vaes, 2015Puvia, E., & Vaes, J. (2015). Promoters versus victims of objectification: Why women dehumanize sexually objectified female targets. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 28(1), 63-93. Retrieved from: https://www.cairn.info/revue-internationale-de-psychologie-sociale-2015-1-page-63.htm

https://www.cairn.info/revue-internation...

).

Beyond being treated as an object, a woman may be transformed into a commodity (Hartsock, 2004Hartsock, N. C. M. (2004). Women and/as Commodities: a brief meditation. Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cashiers De La Femme, 23(3-4), 14-17. Retrieved from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1009.3518&rep=rep1&type=pdf

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/dow...

), that is to say, into something which possesses value when used (material goods useful to human beings), sold, or exchanged (which makes it alienable or exchangeable for other commodities), and of low differentiation (Marx, 1936Marx, K. (1936). Capital: A critique of political economy. New York: The Modern Library.; Belk et al., 1989Belk, R. W., Wallendorf, M., & Sherry Jr, J. F. (1989). The sacred and the profane in consumer behavior: Theodicy on the odyssey. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(1), 1-38. https://doi.org/10.1086/209191

https://doi.org/10.1086/209191...

; Kopytoff, 1986Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process. In The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edit by Arjun Appadurai (pp. 64-92). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.).

The process of the transformation of a human being - or, more specifically, of a woman - into a commodity is defined as commodification (Kopytoff, 1986Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process. In The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edit by Arjun Appadurai (pp. 64-92). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.). Thus, a woman is transformed into a commodity when she becomes a unit under someone else’s control (Kopytoff, 1986Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process. In The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edit by Arjun Appadurai (pp. 64-92). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.). For Williams (2002)Williams, C. C. (2002). A critical evaluation of the commodification thesis. The Sociological Review, 50(4), 525-542. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2286998

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?...

, the commodification of human beings means putting a price label on someone who should not be commercialized, transforming that someone into something which can be commercialized because he/she comes thus to have value for sale, exchange, or use. For Hirschman & Hill (1999Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (1999). On human commoditization: A model based upon African-American slavery. In Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 26 pp. 394-398). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research., 2000)Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (2000). On human commoditization and resistance: A model based upon Buchenwald concentration camp. Psychology& Marketing, 17(6), 469-491. http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200006)17:6%3C469::AID-MAR3%3E3.0.CO;2-3

http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(2...

, commodification also consists of transforming people into others’ property, as occurs in slavery or concentration camps, which shows that commodification is not limited to the world of objects (Kopytoff, 1986Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process. In The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edit by Arjun Appadurai (pp. 64-92). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.).

Factual examples demonstrate how women can be treated as commodities: there is a region in China where women are disposed of and controlled by men or other people. As other’s property, they may be sold or exchanged, not just for money, but for other goods, services, or masculine honor (Hirschman & Hill, 1994Hirschman, E. C., & Stern, B. B. (1994). Women as commodities: prostitution as depicted in the blue angel, pretty baby, and pretty woman (Vol. 21, pp. 576-581). Lancaster: ACR North American Advances.; Henriot, 2012Henriot, C. (2012). Supplying female bodies: Labor migration, sex work, and the commoditization of women in colonial Indochina and contempory Vietnam. Journal of Vietnamese Studies, 7(1), 1-9. Http://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2012.7.1.1

Http://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2012.7.1.1...

); women are treated as others’ property in various parts of the world as for example in Togo, in Africa, where a women is her husband’s - and his family’s - property, even after his death (Moore, 2008Moore, A. R. (2008). Types of violence against women and factors influencing intimate partner violence in Togo (West Africa). Journal of Family Violence, 23(8), 777-783. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9203-6

http://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9203-6...

); in Vietnam, women are sold as fiancées and wives (Henriot, 2012Henriot, C. (2012). Supplying female bodies: Labor migration, sex work, and the commoditization of women in colonial Indochina and contempory Vietnam. Journal of Vietnamese Studies, 7(1), 1-9. Http://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2012.7.1.1

Http://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2012.7.1.1...

); in various places, women are presented as trophies by executives, depending on how young, blond, slender, and beautiful they are, thus demonstrating the importance of the visual aspect of women’s bodies (Hartsock, 2004Hartsock, N. C. M. (2004). Women and/as Commodities: a brief meditation. Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cashiers De La Femme, 23(3-4), 14-17. Retrieved from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1009.3518&rep=rep1&type=pdf

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/dow...

); men of the Huaulu people of Seram (eastern Indonesia) state that they buy their wives and pay a high price for them, which shows the value of use and commercialization which women possess for them (Valeri, 1994Valeri, V. (1994). Buying women but not selling them: gift and commodity exchange in Huaulu alliance. Man, 29(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.2307/2803508

https://doi.org/10.2307/2803508...

).

METHODOLOGY

In our study, we used 20 in-depth interviews (of the one-to-one type) and documentary analysis as our principle source for the collection of data, the interviews being undertaken in two phases, held in the years 2017 and 2018, and the documentary analysis also being undertaken during those two years. Based on the precepts of Lincoln and Guba (1985)Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. and Leech and Onwuegbuzie (2007)Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 557-584. http://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557

http://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.55...

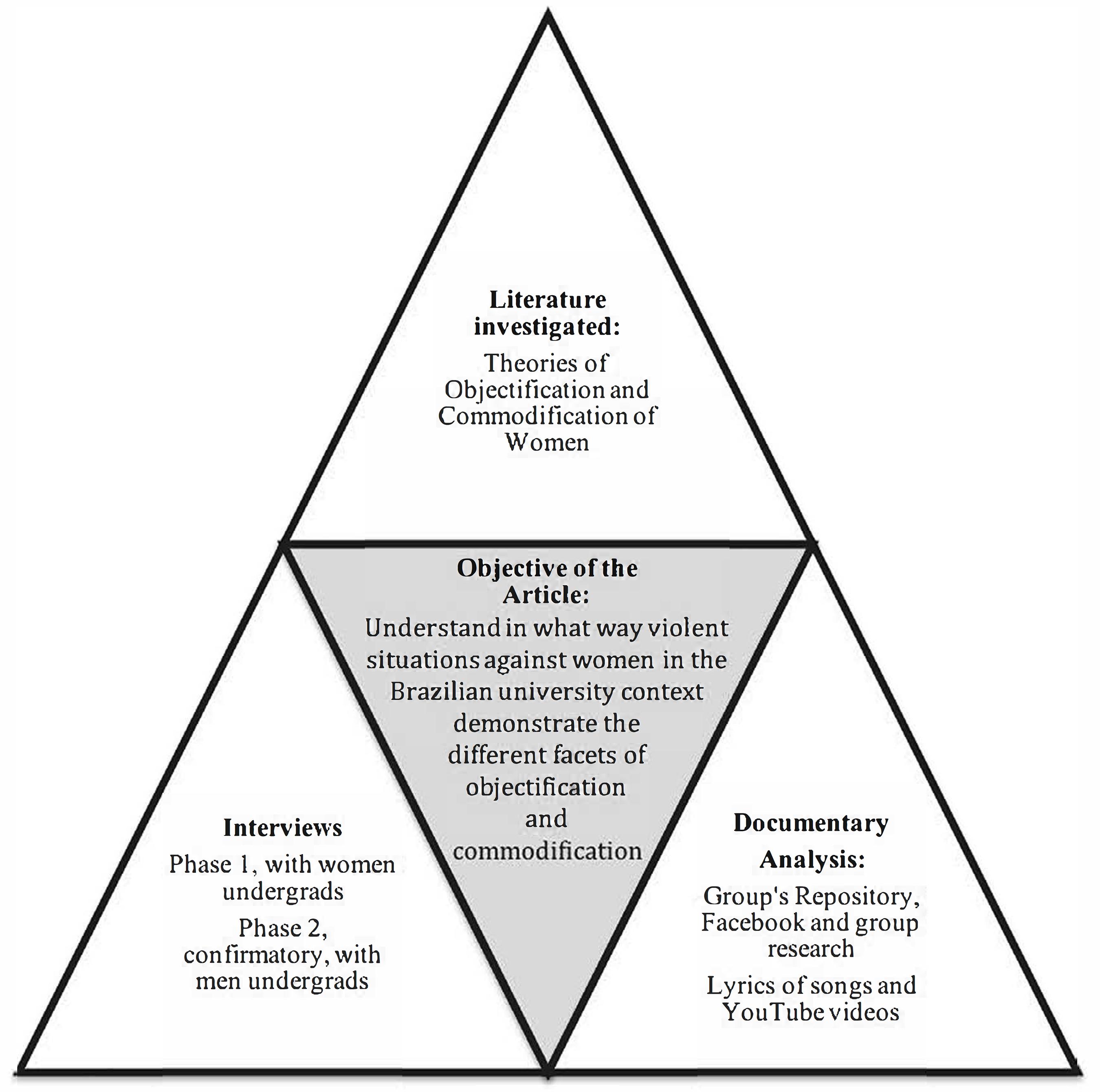

, on the importance of data triangulation for the internal validity of qualitative studies, Figure 1 provides a summary of the data sources used in the article, which are related to our central objective.

Based on this scheme, data collection procedures and analysis strategies for the article will be presented.

Data collection procedures

We adopted in-depth interviews as the main source of data collection for the study, and organized them in two phases, one with fifteen girls and the other with five boys, in order to reduce the selection bias of our study and obtain broader views on the phenomenon investigated. Among the girls, nine belong to the feminist collective, the main group responsible for reports of objectification and commodification of women, three belong to the athletic association, two belong to the academic directory, and one belongs to the band. As for the boys, two are members of the band, one is a member of the academic directory, and two are members of the athletic association.

After conducting informal dialogues with students at the institution under analysis, conducting research on social networks, and taking the initiative to place one of the authors of this article as a member of the feminist collective’s Facebook group, we note that the feminist collective is primarily responsible for registering girls’ reports who have already suffered some type of violence, physical or verbal, in the university environment we investigated, whether these girls are members of the feminist collective or not. As a natural consequence of this characteristic, our research focused on listening, therefore, to those who are responsible for recording the occurrences, and those who eventually witnessed or experienced part of these reports. This is the main reason why we focused the interviews on women members of the collective. Additionally, we heard six girls who are not part of the collective, but who are in university groups in which there have already been reports of gender violence. We confirm the existence of the reports brought after listening to five boys who are part of the same university groups, but who are not part of the feminist collective.

In the first phase of the interviews, in the second semester of 2017, fifteen young women who are or were taking the undergraduate Administration course in a traditional, private, Brazilian institution of university education were heard. Open-type questions were asked to encourage the free expression of the thought and feelings of the interviewees.

Thirteen interviews were held in the candidates’ presence and two were held via Skype, lasting for an average of one hour and twenty-two minutes. The content of the interviews was recorded digitally, with the participants’ consent, and transcribed in full. The initial selection criteria of the interviewees limited them to candidates of the female sex who had had some kind of involvement with feminism during their undergraduate course through feminist organizations. The first three candidates interviewed were selected because of their constant activity in the feminist organization of the university where they study. The sampling process was continued with the use of the snowballing technique (Patton, 2002Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage.; Martin & Eisenhardt, 2010Martin, J. A., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2010). Rewiring: Cross-business-unit collaborations in multi-business organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(2), 265-301. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.49388795

https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.4938879...

), in which other key informants were identified by the first interviewees, after being questioned as to their knowledge of other colleagues with the required characteristics.

To learn about the role of girls in the feminist group, one of the researchers in this article participated in face-to-face meetings and Facebook groups of the feminist collective, with the consent of the members, was able to closely check the performance of those involved. With this procedure, it was possible to understand that the participation of these students was related to the organization of awareness actions at the Higher Education Institution (HEI) (producing posters to be placed at the HEI facilities, going from room to room talking about the feminist collective, creating text for the feminist collective’s blog and Facebook page), rotation of students who would participate in support points at parties (to help in cases of violence against students at HEI events).

In addition, these students actively participated in the Facebook discussions about situations involving issues related to topics of interest to the feminist collective of the HEI. The Facebook groups investigated are private and restricted to students or alumni of the HEI. There are some professors and staff who also participate in the group. In this group (about 9,500 members), there are several issues related to the student’s context, that is, issues about subject contents, doubts about days and times of classes, recommendations from reviewers of academic works, opinions about the methodology of professors, invitations to parties and other university events, disclosure of items found or lost in the HEI environment, and there are also testimonies about different situations, such as cases of harassment, homophobia, racism, which are the posts with the greatest interaction and discussion among students due to the diversity of opinions. These are also the most important posts for the purpose of our article.

We emphasize that our access to the interviewees occurred for some reasons. First, because we are university professors, which facilitated our network of contacts to talk to students, even if they were from another educational institution. Second, we already had some kind of contact with the educational institution analyzed. Finally, our access was facilitated, at first, by women participating in this research project.

In the second phase of the interviews, which occurred during the second semester of 2018, we heard five young men who are or were studying in the same undergraduate course as the girls. We chose to interview the boys so that we could compare the view of both genders about the phenomenon investigated, with a view to reducing a possible selection bias that would exist if we had interviewed only girls. Both with the girls and the boys, the face-to-face interviews took place, mostly, in the educational institution analyzed, in rooms suitable for individual conversations and through a relaxed and informal atmosphere, typical of university environments. We understand that this atmosphere contributed for the interviewees to freely express their feelings and perceptions about the research theme. Table 1 shows the profile of the participants.

It is noteworthy that in the second phase of data collection, we initially selected boys members of the band, athletic association, and academic directory. We selected these boys mainly after the girls reported cases of objectification and commodification associated with these three groups. Based on these reports, we interviewed its most active members, in order to respect the importance of the views of girls and boys. After conducting five interviews, we noticed that the girls’ reports were confirmed by the boys and, for this reason, despite having started from an apparently low number of male respondents, we concluded the data collection phase, as we had reached a saturation of responses present in the view of male respondents, that is, confirming the girls’ reports.

We thus began with the semi-structured course for our analysis, which was fed after the analysis of the replies of the girls interviewed. This sequence was organized to contribute on four dimensions: (a) the trajectory of the student in the institution, (b) his role and activity in different student groups, (c) his critical position with regard to these groups, and (d) the situations of objectification and commodification experienced or witnessed by the students.

Our principal purpose in this phase was the verification of points of convergence/divergence as between the perceptions of men and women with regard to objectification and commodification, thus increasing the internal validity of the research (Creswell, 2003Creswell, J. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.). The men heard were selected because they had exercised an active role in student groups within the institution (e.g., band responsible to sing during sport events and parties, academic board and groups) - our purpose was to select individuals who might have witnessed the situations initially described by the girls and who, for that reason, would be able to confirm or refute the girls’ versions, giving rise to different interpretations of the phenomenon investigated (Patton, 2002Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage.). After these five in-depth interviews, it was observed that the reports presented by the girls were fully confirmed by the boys’, which was why the interviews were discontinued.

It is noteworthy that part of the university parties analyzed are promoted is student associations of the investigated educational institution. In this case, the parties are open to students from different educational institutions, from the most varied courses. There are also parties that are organized by a larger group of student associations in specific areas of knowledge, such as Economics, Engineering, Law, and Administration. These two scenarios bring us to a context in which the set of parties analyzed in the article mainly concerns the context of students from Public and Private Administration, but that also includes the presence of students from other areas of knowledge. We understand that this characteristic contributes, to some extent, to the applicability of our results to different university contexts.

With regard to the documentary analysis, while the interviews were underway we had access to the documents of the feminist group acting in the teaching institution, available on a data storage site. On this site, there are campaigns undertaken by the group against gender inequality and research projects on gender questions undertaken by members of the group, which served as support for our data analysis, research questions which were frequently undertaken after the university parties.

Beyond the documents of the group and the social networks, we also analyzed the 25 lyrics composed and sung by two bands mainly of masculine students of the institution, and videos published on YouTube about gymkhanas for the reception of new arrivals for the course, promoted by veteran students of the institution. The three sources contained content of a strongly macho, sexual, and aggressive nature, which is why access to these documents was fundamental, enabling us to complement the data collected during the two phases of the interviews and to achieve the purpose of the article on the basis of our scheme of triangulation of the data.

Data analysis strategy

To deal with the data collected, the 27-plus hours of interviews, totaling 378 pages with single spacing and Times New Roman size 12 type, were transcribed. There was, therefore, careful control of the data-collection, their coding, classification, and analysis (Miles & Huberman, 1994Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.). The lyrics of the 25 songs were analyzed in conjunction with the respondents’ responses. The same categories of the interviews guided the lyrics of the songs, as well as the videos.

The transcriptions were transferred to Atlas TI software, appropriate for the qualitative analysis (Friese, 2014Friese, S. (2014). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS.ti. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.), and the coding was undertaken line-by-line to identify the principal concepts or codes (Strauss & Corbin, 1990Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.). The process of analysis recommended by the grounded theory technique, which involves three kinds of coding - open, axial, and selective -, was adopted. This choice was made because the research also possesses an inductive character, given that we began the research with the data-collection and later explored the information to see which themes or questions emerged from the field, which is aligned with our choice of non-structured planning in the first phase of the study, following the precepts of Glaser, Strauss, and Strutzel (1968)Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L. & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nursing research, 17(4), 364. Retrieved from: https://journals.lww.com/nursingresearchonline/Citation/1968/07000/The_Discovery_of_Grounded_Theory__Strategies_for.14.aspx

https://journals.lww.com/nursingresearch...

and Strauss and Corbin (1990)Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage..

In the first phase of the codification, the data were analyzed in an open manner on the basis of keywords (Strauss & Corbin, 1990Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.; Locke, 2001Locke, K. (2001). Grounded theory in management research. Thousand Oaks: Sage .). Sequentially, in the stage of axial codification, we analyzed the relations between these keywords and grouped them in categories and subcategories according to their nature and properties (Corbin & Strauss, 2015Corbin, J.M., & Strauss, A.L. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage: Thousand Oaks.). Finally, during the selective codification, we grouped, refined, and shuffled these categories and subcategories of similar character and properties to regroup them. The grouping process continued until the categories were clearly identified, expressed in their causal and environmental conditions, and, principally, achieved the objectives of the research project (Glaser, 1992Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs forcing. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology press.; Strauss & Corbin, 19Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.90). At the end of this process, 346 quotations were selected under 41 codes. Table 2 presents a synthesis of the coding scheme thus constructed.

The coding of this article was done from the data and not from the literature. Thus, when performing the data coding, we realized that they revealed several types of aggressions that the students suffered at parties and other sporting events of the analyzed HEI. This violence was related to physical, sexual, emotional, and moral issues. After these initial perceptions, we investigated Brazilian law number 11.340 (Lei n. 11.340, 2006Lei n. 11.340, de 7 de Agosto, 2006. (2006). Cria mecanismos para coibir a violência doméstica e familiar contra a mulher, nos termos do § 8º do art. 226 da Constituição Federal, da Convenção sobre a Eliminação de Todas as Formas de Discriminação contra as Mulheres e da Convenção Interamericana para Prevenir, Punir e Erradicar a Violência contra a Mulher; dispõe sobre a criação dos Juizados de Violência Doméstica e Familiar contra a Mulher; altera o Código de Processo Penal, o Código Penal e a Lei de Execução Penal; e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União. Brasília, DF.). This law helped us to categorize more precisely the types of domestic and family violence committed against woman, and served as a basis for defining the dimensions chosen for the analysis.

The dimensions of violence described in the law are: physical violence, psychological violence, sexual violence, patrimonial violence, and moral violence. The only form of violence that was not relevant in the analysis of the data was patrimonial violence. Thus, the data analysis was based on these dimensions, when we realized that from the objectification of these dimensions, they went through a process of commodification as well, that is, they became something that has value when it is used, sold or exchanged, which has low differentiation and which becomes a unit under someone else’s control.

On this basis, we arrived at the results and the discussion with the literature, which are set out below.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Woman perceived and behaving as an object

The patriarchal structure present in Brazilian culture contributes to women’s being seen and treated as subjects (Nussbaum, 1999Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.). For the interviewee Vítor, 23, “... society is patriarchal and is based on a relation in which you have the man as the head of the family and normally it’s he who gives the orders”. Situations expressing machismo may be witnessed in various contexts, including the university context. Lucas, 26, relates that he has witnessed evidences of machismo in the faculty, “I have lived through and seen many cases of teachers’ making macho comments in the classroom and even harassing (women) students.”

The theory of objectification suggests that Western culture contributes to women’s internalizing an objectifying view of their own bodies, whereby they worry about their own physical appearance (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997....

).

Objectification leads people into concentrating on their physical characteristics to the detriment of their mental and moral status, and the emphasis on women’s physical attributes may reduce their perception of their competence (Loughnan et al., 2013Loughnan, S., Pina, A., Vasquez, E. A., & Puvia, E. (2013). Sexual objectification increases rape victim blame and decreases perceived suffering. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(4), 455-461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313485718

https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313485718...

; Gray, Knobe, Sheskin, Bloom, and Barrett, 2011Gray, K., Knobe, J., Sheskin, M., Bloom, P., & Barrett, L. F. (2011). More than a body: Mind perception and the nature of objectification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1207-1220. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0025883

http://doi.org/10.1037/a0025883...

). On being objectified, girls suffer personal and professional consequences, denominated auto-objectification by Fredrickson and Roberts (1997)Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997....

.

The women’s interviews revealed the consequences of the objectification they had undergone, whether personally or professionally, including: loss of confidence in their ability to perform class-room activities; excessive concern with their bodies; denial of their basic alimentary desires; fear when choosing the profession they are going to follow because of gender; the feeling of a lack of ability to take up positions of leadership, especially when they were involved with boys in their daily activities.

Adriana, 23, relates that when she took over the presidency of a student organization she was very afraid of exercising her activities: “Even as president I was still insecure, I did not go to speak to the coordinator, it was the general secretary and the vice-president who went, I did not feel secure in doing things. I kept the internal administration, the smaller things, in my hands.” Julieta, 21, tells how she suffers from uncertainty about her own body, and that because of it she imposes limitations on what she eats: “I’m not 100% secure about my body, not about anything I want at the moment I want it, because I’m extremely worried about my body.” Jéssica, 21, felt ashamed to demonstrate her intellectual abilities in the classroom because she was the butt of colleagues’ jokes; she stated: “the teacher wrote some challenges on the board and I was shy of saying I had finished first, because he ridiculed the boys who were present and he used to say that even a woman could do it.”

According to her, she always enjoyed the exact sciences, but chose to do a course in the human sciences, because she was afraid of the difficulties she would face if she chose a predominantly masculine course and because of the experiences of her colleagues: “I have (women) friends who are doing Engineering and who suffer a lot because of it and friends who do Administration who hear ‘a woman does not know how to administer companies.”

However, these situations are often banalized in the girls’ university context. Nussbaum (1999)Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. states that one of the ways of objectifying a person is the negation of their subjectivity, that is to say, the objectifier treats the person as something whose experiences and feelings are unimportant (Joy, Belk, & Bhardwaj 2016Joy, A., Belk, R., & Bhardwaj, R. (2016). Judith Butler on performativity and precarity: Exploratory thoughts on gender and violence in India. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(15-16), 1739-1745. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1076873

https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.10...

). Carlos, 22, states that “The way in which we live makes us banalize these practices which are horrible,” referring to the lyrics of the songs and situations of machismo which arise in the university environment; César, 23, states that the words sung by the faculty band are offensive, but that in the right context there is no problem.

He refers to the court jester who had permission to tell the king the truth as a joke, as if the lyrics of the songs in the party atmosphere represented a parallel space in which it was permitted to say what one really thought of women, as he thus emphasizes: “He (the court jester) is the only person who may speak the truth to the king. Henry VIII was famous because he shut himself away with his court jester because he (the jester) was mad, he is outside the social structure, so he may say just anything.”

We noted this argument used in the Facebook group in the discussion as to whether the lyrics of the songs of an aggressive nature written by students should be continued. This group consists of students and ex-students of the faculty and has some eight thousand members. A post on this topic was appreciated by 166 people and generated 684 comments, from those who agreed that there was the need for a change in the content of the lyrics to those who considered it an exaggeration. Some defended the lyrics: “… university songs, despite being offensive and using words which in the wrong context might suggest machismo and discrimination, in the right context mean nothing of the kind. There is no intention of offending anyone, and within the context, everybody knows that, and I listen to good music at home. University games are synonymous with orgies and fun. That’s the way it works here in São Paulo, in Brazil and in the world.”

The boys defended the idea that at sporting events and parties there are no limits, and one of them uses the word orgy, which alludes to sexual orgies and parties with many drinks. For the students who defend the maintenance of the lyrics of the songs, the phrases sung do not have the intention of offending anyone and that there are the right contexts to express this kind of thought against women, that is to say, within the right context it is acceptable to offend women.

The argument that in the right context the lyrics of songs do not contain offensive meaning could be contested by the analysis of situations of physical and sexual violence committed against the girls at university parties, the principal environment in which the lyrics of the songs are sung. These reports are recorded in the documents relating to research projects undertaken by the feminist group with the students of the faculty to understand possible situations of aggression against them (Machin & Van Leeuwen, 2016Machin, D., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2016). Sound, music and gender in mobile games. Gender & Language, 10(3), 412-432. http://doi.org/10.1558/genl.v10i3.32039

http://doi.org/10.1558/genl.v10i3.32039...

).

One of these research projects was undertaken after a party held in 2014. A questionnaire made available on internet was answered by 212 women students of the faculty and 69% of the respondents stated that they were approached or harassed aggressively at some moment in the party by young men, and 51% of them did not feel comfortable circulating alone at the party. In their description of how they were approached or harassed, the respondents said: “Men insisted on trying to kiss me and when I refused they continued to try to force me to. I had to break away or run to some friend of mine and a man got hold of me, insisting that I was his girlfriend and he didn’t leave me alone, afterwards he pushed me against a wall and tried to force me to kiss him.”

Regarding the various forms of objectification proposed by Nussbaum (1999)Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press., it is clear that the phenomenon has several different aspects, but that these consist of “treating as an object something that is not an object, but rather a human being” (p. 218). However, beyond being objectified, women may also be commodified. We perceived, from the interviewees’ reports, that the situations of abuse and violence demonstrate four ways in which a woman may be commodified in the university context, by: (a) commodification of her body; (b) of her sexuality; (c) of her morality; (d) of her feelings (Kopytoff, 1986Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process. In The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edit by Arjun Appadurai (pp. 64-92). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.; Nussbaum, 1999Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.; Hirschman & Hill, 1999Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (1999). On human commoditization: A model based upon African-American slavery. In Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 26 pp. 394-398). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research., 2000)Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (2000). On human commoditization and resistance: A model based upon Buchenwald concentration camp. Psychology& Marketing, 17(6), 469-491. http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200006)17:6%3C469::AID-MAR3%3E3.0.CO;2-3

http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(2...

. These forms of commodification will be explored in the following section.

Commodified bodies, sexuality, morality, and feelings

“What often happens at parties is that the boys give a girl drink to make her drunk, and afterwards take her elsewhere: to their house, a corner of the party area, or their car to do whatever they want with her and afterwards the girl does not remember what happened” (Mariana, 21).

Mariana’s report reveals a series of abuses that girls suffer during the parties and university sporting events.

Mariana also witnessed other cases of boys at parties who took advantage of a girl who drank to take advantage of her physically. Among the abuses reported are: kissing the girl’s face, neck, and mouth forcibly; pulling her hair or her arm; caressing parts of her body: her breasts, stomach, shoulders, buttocks, and genitalia; using offensive language; pushing, biting, pinching, throwing beer on her head; obliging her to make physical contact, among other examples that indicate the sensation of control that the boys feel with regard to the girls. This situation demonstrates how women can be seen as objects and commodities to be consumed and controlled in accordance with their owners’ interests (Kopytoff, 1986Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process. In The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edit by Arjun Appadurai (pp. 64-92). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.; Nussbaum, 1999Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.; Hirschman & Hill, 1999Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (1999). On human commoditization: A model based upon African-American slavery. In Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 26 pp. 394-398). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research., 2000)Hirschman, E. C., & Hill, R. P. (2000). On human commoditization and resistance: A model based upon Buchenwald concentration camp. Psychology& Marketing, 17(6), 469-491. http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(200006)17:6%3C469::AID-MAR3%3E3.0.CO;2-3

http://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(2...

.

The belief that others can exercise power over the woman’s body - and that she exists to serve - is ancient, profound, deep-rooted, diffused in everyday life, and rarely contested (Dworkin, 1981Dworkin, A. (1981). Men possessing women. New York: Perigee.). Julieta talks about situations in her daily life that demonstrate how she needed to fall in line with the expectations of others, such as members of her family and friends: “... I remember episodes in which my stepmother said, ‘your bra’s showing, cover it up.’ My uncle’s wife saying ‘your body’s good, but you can’t get any fatter, you must stay like that.’ When I was small my hair was curly and I grew up hearing that my hair was ugly, bristling, and that it was not pretty. My cousins are blondes, with smooth hair, and I was physically different from them. Then when I was about 12 years old, I wanted to straighten my hair. I spent 8 years of my life straightening my hair. Until I entered the faculty and met Melissa (founder of the feminist group of the university), and I said: ‘Look at that girl, look at her hair, why should I try to straighten my hair?’” (Julieta, 21).

Gardner (1980)Gardner, C. B. (1980). Passing by: Street remarks, address rights, and the urban female. Sociological Inquiry, 50(3-4), 328-356. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1980.tb00026.x

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1980...

states that women’s bodies are more often subject to other people’s commented assessments, as for example, about their bra showing, about their body’s being acceptable, and about their hair not being pretty, showing that both men and women can objectify a woman.

The feeling of ownership and power that some young men demonstrate with regard to a woman’s body also finds expression in the lyrics of the songs sung by students of the faculty to provoke the rivalry between the universities at the university games. The words say: “Even though you’re not attractive. I’ve come to eat you, you’ll do it free for (the name of the faculty),” “You’re a worthless whore,” “I’m different, I’m going to be president, you the secretary, my cleaner,” “Come to fuck with me, on all fours, face to face, I’ll fuck even your belly button, just don’t kiss me, bitch,” “Vagabond, you don’t feel pain,” “I dirtied the mouths of the lay-downs of the whole city, afterwards I didn’t even kiss her, or create a friendship, afterwards I despised her so much that she fell in love with me” and “That thing isn’t a woman, it’s a thing with a vagina, it only serves to do a blowjob on me.”

Analyzing some of the stanzas of these offensive lyrics, one may perceive masculine sentiments of power and possession regarding the body and sexuality of women. Lucas, 26, tells how he and his colleagues sang, “We’ve come here, just to drink, our sport is in the vagina, to be your boss is our destiny.”

Other lyrics say they found many girls in the street, demonstrating the perception of women as available, accessible, like common objects, without anything that would make them singular, just like a commodity (Kopytoff, 1986Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process. In The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edit by Arjun Appadurai (pp. 64-92). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.). The lyrics refer to the girls as ugly, that is to say, without any beauty that might attract the possessor’s eye, “I don’t want you, you are just too ugly, so go away fatty, go away vagabond, far from my cock,” “I’m going to cover your face with a blanket,” and even so the boy is going to have sexual relations with her, who will do this without charging anything: “You will do it free for (the name of the faculty),” referring thus to the prostitutes who offer sexual services in exchange for money, and making reference once more to the woman as a commodity (Monto & Julka, 2009Monto, M. A., & Julka, D. (2009). Conceiving of sex as a commodity: A study of arrested customers of female street prostitutes. Western Criminology Review, 10(1), 1-14. Retrieved from: https://westerncriminology.org/documents/WCR/v10n1/Monto.pdf

https://westerncriminology.org/documents...

; Rudman & Fetterolf, 2014Rudman, L. A., & Fetterolf, J. C. (2014). Gender and sexual economics: Do women view sex as a female commodity? Psychological Science, 25(7), 1438-1447. http://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614533123.

http://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614533123...

).

When the lyric says, “you’re a worthless prostitute,” and “that’s not a woman, it’s a creature with a vagina, only useful to do a blowjob on me,” the woman comes to possess a value of use, for which she will be used for sexual purposes and afterwards be discarded (Hartsock, 2004Hartsock, N. C. M. (2004). Women and/as Commodities: a brief meditation. Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cashiers De La Femme, 23(3-4), 14-17. Retrieved from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1009.3518&rep=rep1&type=pdf

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/dow...

). The lyrics continue with innumerable vulgar expressions that demonstrate how the woman’s body can be used to satisfy sexual desires, as in a relationship of power, and afterwards be discarded as worthless (Hirschman, 1991Hirschman, E. C. (1991). Exploring the dark side of consumer behavior: Methaphor and ideology in prostitution and pornography. In J. A. Costa (Ed.), GCB - Gender and consumer behavior (vol. 1, pp. 303-314). Salt Lake, UT: Association for Consumer Research.).

In the lyrics of the songs, the woman is objectified and commodified in various ways. The studies of Haslam (2006)Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252-264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr100...

and Morris, Goldenberg, & Boyd (2018)Morris, K. L., Goldenberg, J., & Boyd, P. (2018). Women as animals, women as objects: Evidence for two forms of objectification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(9), 1302-1314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218765739.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218765739...

state that the de-humanization can be mechanistic or animalesque. In mechanistic de-humanization, the woman is objectified for her physical appearance and not for her sexual aspects, that is to say, she is seen as an object that can be used and manipulated. That is why she is portrayed as incapable of feeling pain (Heflick & Goldenberg (2009)Heflick, N. A., & Goldenberg, J. L. (2009). Objectifying Sarah Palin: Evidence that objectification causes women to be perceived as less competent and less fully human. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(3), 598-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.008

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.0...

, as in the passage of the song: “Vagabond, you don’t feel pain,” just as if she were an object, a piece of furniture, for example. In animalesque de-humanization, the objectification focuses on sexual aspects, and the woman is seen as an animal. Thus, she can be used for the satisfaction of her owner’s sexual desires, as in: “lick my whole body, get hold of my cock.”

After the satisfaction of sexual desires, she may still have value of use for her owner, because she will continue to offer services, now as secretary or cleaner, while the boy will exercise intellectual activities as president, as in the passage: “shut your moustached mouth, come and serve my coffee.” Thus, the woman can be seen as a commodity to be used, discarded, and used again at any moment.

Another song sung at the university parties received the name “Daddy’s secretary,” and passages of this song say: “She has a moustache, she looks like a skivvy, offering her cunt is her greatest hobby, come here, I’ll hire you;” “Come to me, come to be fucked, serve my coffee and suck me, but I’m not going to kiss you;” “When I fuck you cover your face because I don’t want to see you, you are too ugly, shave that moustache;” “Come to be Daddy’s secretary.”

The woman continues to be seen as ugly and is diminished to the status of rendering sexual and domestic services (Hartsock, 2004Hartsock, N. C. M. (2004). Women and/as Commodities: a brief meditation. Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cashiers De La Femme, 23(3-4), 14-17. Retrieved from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1009.3518&rep=rep1&type=pdf

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/dow...

). Another strong indication of the commodification of the body and sexuality are the passages: “Just don’t kiss me, bitch” and “But I’m not going to kiss you,” in which the lyrics say that there will be no kissing in any of the relations, because kissing indicates a more intimate and sentimental contact between them, revealing the relationship’s ephemeral and transient nature.

Commodification can be observed in situations in which men believe that women are the property of other men and, as they are accompanied, they may feel safe and protected, but when they are alone, their bodies are available to be possessed by other men. Pietra, 20, feels uncomfortable about simple things in her routine such as getting into an elevator at the university, because she perceives the looks and the attempts to invade the privacy of her body, because she is without her boyfriend. Henrique, 23, states that when he is at his girlfriend’s side, the boys respect her, but if he’s some paces behind her, he realizes how much his presence is necessary to inhibit other boys’ harassment. “There are many guys who hold my girlfriend’s hand in the middle of a party. When I am holding her hand, no one does anything. But when I’m two steps away they think they can do just anything. They hold her hand, touch her waist, caress her hair.”

Another fact that demonstrates the thinking of certain men regarding their belief that women are other men’s property is the fact that they apologize to the boyfriend because they thought that the woman was available. Henrique, 23, says that when boys approach his girlfriend at a party, he speaks to them and the boys’ reaction is to apologize to him, “I put my hand on the boy’s shoulder and say ‘bro’ and the boy immediately says ‘no, I did wrongly, forgive me.”

However, men do not always succeed in respecting what they consider to be others’ property. Belk (1988)Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139-168. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

https://doi.org/10.1086/209154...

argues that the owner seeks to control his belongings, but he also has an interest in others’ possessing them too, that is to say, that they should enter the field of rivalry when they understand that they possess less than the other person. This is why situations arise in which a man commodifies a woman even when she is accompanied by another man, as in the example quoted by Izis, in which she witnessed a fight between two boys because of a woman at a university party: