Abstract

Mammals are charismatic organisms that play a fundamental role in ecological functions and ecosystem services, such as pollination, seed dispersal, nutrient cycling, and pest control. The state of São Paulo represents only 3% of the Brazilian territory but holds 33% of its mammalian diversity. Most of its territory is dominated by agriculture, pastures, and urban areas which directly affect the diversity and persistence of mammals in the landscape. In addition, São Paulo has the largest port in Latin America and the largest offshore oil reservoir in Brazil, with a 600 km stretch of coastline with several marine mammal species. These human-made infrastructures affect the diversity, distribution, ecology, and the future of mammals in the state. Here, we answer five main questions: 1) What is the diversity of wild mammals in São Paulo state? 2) Where are they? 3) What is their positive and negative impact on human well-being? 4) How do mammals thrive in human-modified landscapes? 5) What is the future of mammals in the state? The state of São Paulo holds 255 species of native mammals, with four endemic species, two of them globally endangered. At least six species (two marsupials, Giant otter, Pampas deer, Brazilian dwarf brocket deer, and Giant armadillo) were extirpated from the state due to hunting and habitat loss. The intense human land use in the state forced many mammalian species to change their diet to cope with the intense fragmentation and agriculture. Large-scale monoculture has facilitated the invasion of exotic species such as wild boars (javali) and the European hare. Several “savanna-dwelling” species are expanding their ranges (Maned wolf, Brocket deer) over deforested areas and probably reflect changes towards a drier climate. Because the state has the largest road system, about 40,000 mammals from 33 species are killed per year in collisions causing an economic loss of 12 million dollars/year. The diversity of mammals is concentrated in the largest forest remnants of Serra do Mar and in the interior of the State, mainly in the regions of Ribeirão Preto and Jundiaí. Sampling gaps are concentrated throughout the interior of the state, particularly in the northwest region. Wild mammals play a fundamental role in many ecosystem services, but they can also be a concern in bringing new emergent diseases to humans. Although the taxonomy of mammals seems to be well known, we show that new species are continuously being discovered in the state. Therefore, continuous surveys using traditional and new technologies (eDNA, iDNA, drones), long-term population monitoring, investigation of the interface of human-wildlife conflict, and understanding of the unique ecosystem role played by mammals are future avenues for promoting sustainable green landscapes allied to human well-being in the state. The planting of forest or savanna corridors, particularly along with major river systems, in the plateau, controlling illegal hunting in the coastal areas, managing fire regimes in the Cerrado, and mitigating roadkill must be prioritized to protect this outstanding mammal diversity.

Keywords:

e-DNA; iDNA; extinction risk; Atlantic Forest; Cerrado; Araucaria mixed forest; stable isotopes; line transect; camera trapping

Resumo

Os mamíferos são organismos carismáticos que desempenham um papel fundamental na função ecológica e nos serviços ecossistêmicos, como polinização, dispersão de sementes, ciclagem de nutrientes e controle de pragas. O Estado de São Paulo representa apenas 3% do território brasileiro, mas detém 33% da diversidade de mamíferos. A maior parte de seu território é dominado pela agricultura, pastagens e áreas urbanas que afetam diretamente a diversidade e a persistência dos mamíferos na paisagem. Além disso, São Paulo possui o maior porto da América Latina e o maior reservatório de petróleo costeiro do Brasil, com 600 km de extensão de litoral com diversas espécies de mamíferos marinhos. Essas infraestruturas afetam a diversidade, distribuição, ecologia e o futuro dos mamíferos no estado. Aqui, respondemos cinco perguntas principais: 1) Qual é a diversidade de mamíferos silvestres no Estado de São Paulo? 2) Onde eles ocorrem? 3) Qual é o seu impacto positivo e negativo no bem-estar humano? 4) Como os mamíferos persistem em paisagens modificadas pelo homem? 5) Qual é o futuro dos mamíferos no estado? O estado de São Paulo possui 255 espécies de mamíferos nativos, com quatro espécies endêmicas, duas delas globalmente ameaçadas de extinção. Pelo menos seis espécies (dois marsupiais, ariranha, veado-campeiro, veado-cambuta e tatu-canastra) foram extirpadas do estado devido à caça e perda de habitat. O intenso uso humano da terra no estado forçou muitas espécies de mamíferos a mudar sua dieta para lidar com a intensa fragmentação e agricultura. A monocultura em larga escala facilitou a invasão de espécies exóticas, como porcos selvagens (javaporco) e a lebre europeia. Várias espécies de áreas abertas estão expandindo suas áreas de distribuição (lobo-guará, veado-catingueiro) sobre áreas desmatadas e provavelmente refletem mudanças em direção a um clima mais seco. Como o estado possui o maior sistema rodoviário do Brasil, cerca de 40 mil mamíferos de 33 espécies são mortos por ano em colisões, causando um prejuízo econômico de 12 milhões de dólares/ano. A diversidade de mamíferos está concentrada nos maiores remanescentes florestais da Serra do Mar e no interior do Estado, principalmente nas regiões de Ribeirão Preto e Jundiaí. As lacunas amostrais estão concentradas em todo o interior do estado, principalmente na região noroeste. Os mamíferos silvestres desempenham um papel fundamental em muitos serviços ecossistêmicos, mas também podem ser uma preocupação em trazer novas doenças emergentes para as populações humanas. Embora a taxonomia de mamíferos pareça ser bem conhecida, mostramos que novas espécies estão sendo continuamente descobertas no estado. Portanto, pesquisas usando tecnologias tradicionais e novas (eDNA, iDNA, drones), monitoramento populacional de longo prazo, a investigação da interface do conflito homem-vida selvagem e a compreensão do papel único no ecossistema desempenhado pelos mamíferos são um caminho futuro para promover uma paisagem verde sustentável aliada ao bem-estar humano no estado. O plantio de corredores florestais ou de cerrado, principalmente junto aos principais sistemas fluviais, no planalto, o controle da caça ilegal nas áreas costeiras, o manejo dos regimes de fogo no Cerrado e a mitigação dos atropelamentos devem ser uma prioridade para proteger essa notável diversidade de mamíferos.

Palavras-chave

e-DNA; iDNA; risco de extinção; Mata Atlântica; Cerrado; Floresta de Araucária; isótopos estáveis; transecções lineares; armadilhas fotográficas

1. Introduction

Wild animals represent an insignificant part of the world’s biomass when compared to plants and microbes. Plants make a whopping 81%, microorganisms 17% and wild animals only 0.001% of the world’s living biomass (Bar-On et al. 2018BAR-ON, Y. M., R. PHILLIPS & R. MILO. 2018. The biomass distribution on Earth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:6506–6511.). However, although wild animals represent small biomass, they are very important for the Earth’s biodiversity and climate regulation (Malhi et al. 2022MALHI, Y., T. LANDER, E. LE ROUX, N. STEVENS, M. MACIAS-FAURIA, L. WEDDING, C. GIRARDIN, J. Å. KRISTENSEN, C. J. SANDOM & T. D. EVANS. 2022. The role of large wild animals in climate change mitigation and adaptation. Current Biology 32:R181–R196.). Among wild animals, mammals play a fundamental role in ecosystem functioning and services, such as pollination, seed dispersal, and pest control. Mammals also play several disservices to humans, particularly when they raid crops, transmit zoonotic diseases, or prey upon livestock.

Brazil has 770 species of mammals (Quintela et al. 2020QUINTELA, F. M., D. A. R. CA & O. A. FEIJ. 2020. Updated and annotated checklist of recent mammals from Brazil. An Acad Bras Cienc 92 Suppl 2:e20191004.; Abreu et al. 2021ABREU, E. F., D. CASALI, R. COSTA-ARAÚJO, G. S. T. GARBINO, G. S. LIBARDI, D. LORETTO, A. C. LOSS, M. MARMONTEL, L. M. MORAS, M. C. NASCIMENTO, M. L. OLIVEIRA, S. E. PAVAN, & F. P. TIRELLI. (2021). Lista de Mamíferos do Brasil (2021-2) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5802047

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/...

), and São Paulo, which corresponds to less than 3% of the Brazilian territory, has 33% of those species. This high diversity lies in the considerable diversity of ecosystems and climate, such as savannas (Cerrado), dry and humid Atlantic Forests, Araucaria mixed forests, and the complex evolutionary history and diversification of the mammalian fauna (Vivo et al. 2011VIVO, M. D., A. P. CARMIGNOTTO, R. GREGORIN, E. HINGST-ZAHER, G. E. IACK-XIMENES, M. MIRETZKI, A. R. PERCEQUILLO, M. M. ROLLO JUNIOR, R. V. ROSSI & V. A. TADDI. 2011. Checklist of mammals from São Paulo State, Brazil. Biota Neotropica 11:111–131.). The long history of research and network of protected areas (including the largest remaining area of Atlantic Forest) make São Paulo an ideal case where green sustainable landscapes, allied to economic growth and social benefits, are possible.

Here we review the diversity of mammal species in the State of São Paulo, their distribution, how they thrive in the human-modified landscapes, and discuss the future of mammal diversity. We summarize decades of research done in São Paulo, most of them supported by the Biota FAPESP program in the last 20 years.

What is the diversity of mammals in São Paulo state?

New inventories, catalogs, systematic revisions, and taxonomic studies continue to increase the number of mammal species recorded in São Paulo (Garbino 2016GARBINO, G. S. T. 2016. Research on bats (Chiroptera) from the state of São Paulo, southeastern Brazil: annotated species list and bibliographic review. Arquivos de Zoologia 47.; Fegies et al. 2021FEGIES, A. C., A. P. CARMIGNOTTO, M. F. PEREZ, M. D. GUILARDI & A. C. LESSINGER. 2021. Molecular Phylogeny of Cryptonanus (Didelphidae: Thylamyini): Evidence for a recent and complex diversification in South American open biomes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 162:107213.). The increasing use of pitfall traps to sample small mammals have provided several new specimens of marsupials and rodents aiding in new species descriptions, species range delimitation, and small mammal community characterization (Bovendorp et al. 2017aBOVENDORP, R. S., R. A. MCCLEERY & M. GALETTI. 2017a. Optimising sampling methods for small mammal communities in Neotropical rainforests. Mammal Review 47:148–158.). In addition, climate change and intensive land use change have created suitable habitats for colonizing “savanna-associated” species (Sales et al. 2020SALES, L. P., M. GALETTI & M. M. PIRES. 2020. Climate and land-use change will lead to a faunal “savannization” on tropical rainforests. Glob Chang Biol 26:7036–7044.).

Vivo et al. (2011VIVO, M. D., A. P. CARMIGNOTTO, R. GREGORIN, E. HINGST-ZAHER, G. E. IACK-XIMENES, M. MIRETZKI, A. R. PERCEQUILLO, M. M. ROLLO JUNIOR, R. V. ROSSI & V. A. TADDI. 2011. Checklist of mammals from São Paulo State, Brazil. Biota Neotropica 11:111–131.) listed 230 mammals (205 terrestrial and 25 marine species) with attested records in São Paulo state. After 11 years, we have increased our knowledge of the mammals present in the state, including recently described species with restricted distributional range (5 species – three rodents, one bat, and one marsupial), identity confirmation and taxonomic revalidation of nominal taxa previously included in the synonymy of other species (12 species), as well as new records of rarely sampled species in the state (13 species – five bats, five rodents, two felids and one canid), totaling 17 new terrestrial and 13 marine species for the list. Other species had their names excluded (Monodelphis theresa) or corrected (Philander quica), based on taxonomic approaches (17 species). On the other hand, some records (Gardnerycteris crenulatum, Micronycteris brosseti and Uroderma bilobatum) were removed from the list since they were not confirmed (Garbino, 2016GARBINO, G. S. T. 2016. Research on bats (Chiroptera) from the state of São Paulo, southeastern Brazil: annotated species list and bibliographic review. Arquivos de Zoologia 47.). Therefore, São Paulo currently harbors 217 terrestrial and 38 marine species, totaling 255 mammalian native species (Supplementary Table S1 Supplementary Material The following online material is available for this article: Appendix 1. Checklist of the Mammals from São Paulo State. Appendix 2. Distribution of each mammalian order in São Paulo state. ), an impressive growth of 2.3 species/year. Four species (Black-lion tamarin Leontopithecus chrysopygus, one terrestrial rodent Akodon sanctipaulensis and two arboreal rodents Phyllomys kerri, and P. thomasi) are endemic to the state. Two of these endemic species are Data Deficient and two are Endangered (www.iucnredlist.org).

From an evolutionary and conservation point of view, studies in population genetics are a critical key in illuminating the Evolutionary Significant Units (ESUs). For instance, tapirs inhabiting the large Atlantic Forest corridor are genetically different from the inland and coastal populations (Saranholi et al. 2022SARANHOLI, B. H., A. SANCHES, J. F. M. RAMÍREZ, C. D. S. CARVALHO, M. GALETTI & P. M. GALETTI JR. 2022. Long-term persistence of the large mammal lowland tapir is at risk in the largest Atlantic forest corridor. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation:00–00.). It appears that even within large-sized mammals, fine-scale genetic differentiation may be more frequent than thought before, and this can be increased by landscape modifications, as also reported within Puma concolor (Saranholi et al. 2017SARANHOLI, B. H., K. CHÁVEZ-CONGRAINS & P. M. GALETTI. 2017. Evidence of recent fine-scale population structuring in south American Puma concolor. Diversity 9:44.).

Although the phylogenetic diversity of São Paulo mammals represents a subset of the diversity of Brazilian mammals, the state is well represented in all Orders, except Sirenia (Figure 1).

Phylogeny of the species of mammals in Brazil highlights the species found in São Paulo state.

Where are the mammals in São Paulo state?

São Paulo has the best spatial information on its biodiversity in Brazil; with mammals being studied for over a century. A series of datasets on the distribution of Brazilian mammals are available and we used eight of them to compile a list of species for the state and species richness for 22 watersheds in the state: Atlantic Bats (Muylaert et al. 2017MUYLAERT, R. D. L., R. D. STEVENS, C. E. L. ESBERARD, M. A. R. MELLO, G. S. T. GARBINO, L. H. VARZINCZAK, D. FARIA, M. D. M. WEBER, P. KERCHES ROGERI, A. L. REGOLIN, H. OLIVEIRA, L. D. M. COSTA, M. A. S. BARROS, G. SABINO-SANTOS, JR., M. A. CREPALDI DE MORAIS, V. S. KAVAGUTTI, F. C. PASSOS, E. L. MARJAKANGAS, F. G. M. MAIA, M. C. RIBEIRO & M. GALETTI. 2017. ATLANTIC BATS: a data set of bat communities from the Atlantic Forests of South America. Ecology 98:3227.), Atlantic Camtrap (Lima et al. 2017LIMA, F., BECA, G., MUYLAERT, R.L., JENKINS, C.N., PERILLI, M.L.L., PASCHOAL, A.M.O., MASSARA, R.L., PAGLIA, A.P., CHIARELLO, A.G., GRAIPEL, M.E., CHEREM, J.J., REGOLIN, A.L., OLIVEIRA SANTOS, L.G.R., BROCARDO, C.R., PAVIOLO, A., DI BITETTI, M.S., SCOSS, L.M., ROCHA, F.L., FUSCO-COSTA, R., ROSA, C.A., DA SILVA, M.X., HUFNAGELL, L., SANTOS, P.M., DUARTE, G.T., GUIMARAES, L.N., BAILEY, L.L., RODRIGUES, F.H.G., CUNHA, H.M., FANTACINI, F.M., BATISTA, G.O., BOGONI, J.A., TORTATO, M.A., LUIZ, M.R., PERONI, N., DE CASTILHO, P.V., MACCARINI, T.B., FILHO, V.P., ANGELO, C., CRUZ, P., QUIROGA, V., IEZZI, M.E., VARELA, D., CAVALCANTI, S.M.C., MARTENSEN, A.C., MAGGIORINI, E.V., KEESEN, F.F., NUNES, A.V., LESSA, G.M., CORDEIRO-ESTRELA, P., BELTRAO, M.G., DE ALBUQUERQUE, A.C.F., INGBERMAN, B., CASSANO, C.R., JUNIOR, L.C., RIBEIRO, M.C., GALETTI, M., 2017. ATLANTIC-CAMTRAPS: a dataset of medium and large terrestrial mammal communities in the Atlantic Forest of South America. Ecology 98: 2979.), Atlantic Large Mammals (Souza et al. 2019SOUZA, Y., F. GONÇALVES, L. LAUTENSCHLAGER, P. AKKAWI, C. MENDES, M. CARVALHO, R. BOVENDORP, H. FERNANDES-FERREIRA, C. ROSA & M. GRAIPEL. 2019. ATLANTIC MAMMALS: a data set of assemblages of medium-and large-sized mammals of the Atlantic Forest of South America. Ecology 100:e02785-e02785.), Atlantic Primates (Culot et al. 2019CULOT, L., L. A. PEREIRA, I. AGOSTINI, M. A. B. DE ALMEIDA, R. S. C. ALVES, I. AXIMOFF, A. BAGER, M. C. BALDOVINO, T. R. BELLA, J. C. BICCA-MARQUES, C. BRAGA, C. R. BROCARDO, A. K. N. CAMPELO, G. R. CANALE, J. D. C. CARDOSO, E. CARRANO, D. C. CASANOVA, C. R. CASSANO, E. CASTRO, J. J. CHEREM, A. G. CHIARELLO, B. A. P. COSENZA, R. COSTA-ARAUJO, N. C. D. SILVA, M. S. DI BITETTI, A. S. FERREIRA, P. C. R. FERREIRA, M. S. FIALHO, L. F. FUZESSY, G. S. T. GARBINO, F. O. GARCIA, C. GATTO, C. C. GESTICH, P. R. GONCALVES, N. R. C. GONTIJO, M. E. GRAIPEL, C. E. GUIDORIZZI, R. O. ESPINDOLA HACK, G. P. HASS, R. R. HILARIO, A. HIRSCH, I. HOLZMANN, D. H. HOMEM, H. E. JUNIOR, G. S. JUNIOR, M. C. M. KIERULFF, C. KNOGGE, F. LIMA, E. F. DE LIMA, C. S. MARTINS, A. A. DE LIMA, A. MARTINS, W. P. MARTINS, F. R. DE MELO, R. MELZEW, J. M. D. MIRANDA, F. MIRANDA, A. M. MORAES, T. C. MOREIRA, M. S. DE CASTRO MORINI, M. B. NAGY-REIS, L. OKLANDER, L. DE CARVALHO OLIVEIRA, A. P. PAGLIA, A. PAGOTO, M. PASSAMANI, F. DE CAMARGO PASSOS, C. A. PERES, M. S. DE CAMPOS PERINE, M. P. PINTO, A. R. M. PONTES, M. PORT-CARVALHO, B. PRADO, A. L. REGOLIN, G. C. REZENDE, A. ROCHA, J. D. S. ROCHA, R. R. DE PAULA RODARTE, L. P. SALES, E. D. SANTOS, P. M. SANTOS, C. S. S. BERNARDO, R. SARTORELLO, L. SERRA, E. SETZ, E. S. A. S. DE ALMEIDA, L. H. D. SILVA, P. SILVA, M. SILVEIRA, R. L. SMITH, S. M. DE SOUZA, A. C. SRBEK-ARAUJO, L. C. TREVELIN, C. VALLADARES-PADUA, L. ZAGO, E. MARQUES, S. F. FERRARI, R. BELTRAO-MENDES, D. J. HENZ, F. E. DA VEIGA DA COSTA, I. K. RIBEIRO, L. L. T. QUINTILHAM, M. DUMS, P. M. LOMBARDI, R. T. R. BONIKOWSKI, S. G. AGE, J. P. SOUZA-ALVES, R. CHAGAS, R. CUNHA, M. M. VALENCA-MONTENEGRO, G. LUDWIG, L. JERUSALINSKY, G. BUSS, R. B. DE AZEVEDO, R. F. FILHO, F. BUFALO, L. MILHE, M. M. D. SANTOS, R. SEPULVIDA, D. D. S. FERRAZ, M. B. FARIA, M. C. RIBEIRO & M. GALETTI. 2019. ATLANTIC-PRIMATES: a dataset of communities and occurrences of primates in the Atlantic Forests of South America. Ecology 100:e02525.), Atlantic Small Mammals (Bovendorp et al. 2017bBOVENDORP, R. S., N. VILLAR, E. F. DE ABREU-JUNIOR, C. BELLO, A. L. REGOLIN, A. R. PERCEQUILLO & M. GALETTI. 2017b. Atlantic small-mammal: a dataset of communities of rodents and marsupials of the Atlantic forests of South America. Wiley Online Library.), Neotropical Carnivores (Nagy-Reis et al. 2020NAGY-REIS, M., J. E. D. F. OSHIMA, C. Z. KANDA, F. B. L. PALMEIRA, F. R. DE MELO, R. G. MORATO, L. BONJORNE, M. MAGIOLI, C. LEUCHTENBERGER & F. ROHE. 2020. NEOTROPICAL CARNIVORES: a data set on carnivore distribution in the Neotropics. Wiley Online Library.), and Neotropical Xenarthras (Santos et al. 2019SANTOS, P. M., A. BOCCHIGLIERI, A. G. CHIARELLO, A. P. PAGLIA, A. MOREIRA, A. C. DE SOUZA, A. M. ABBA, A. PAVIOLO, A. GATICA & A. Z. MEDEIRO. 2019. NEOTROPICAL XENARTHRANS: a data set of occurrences of Xenarthran species in the Neotropics. Wiley Online Library.) and summarized the species number information (richness) for the boundaries of the 22 hydrographic regions in the State of São Paulo (Figure 2).

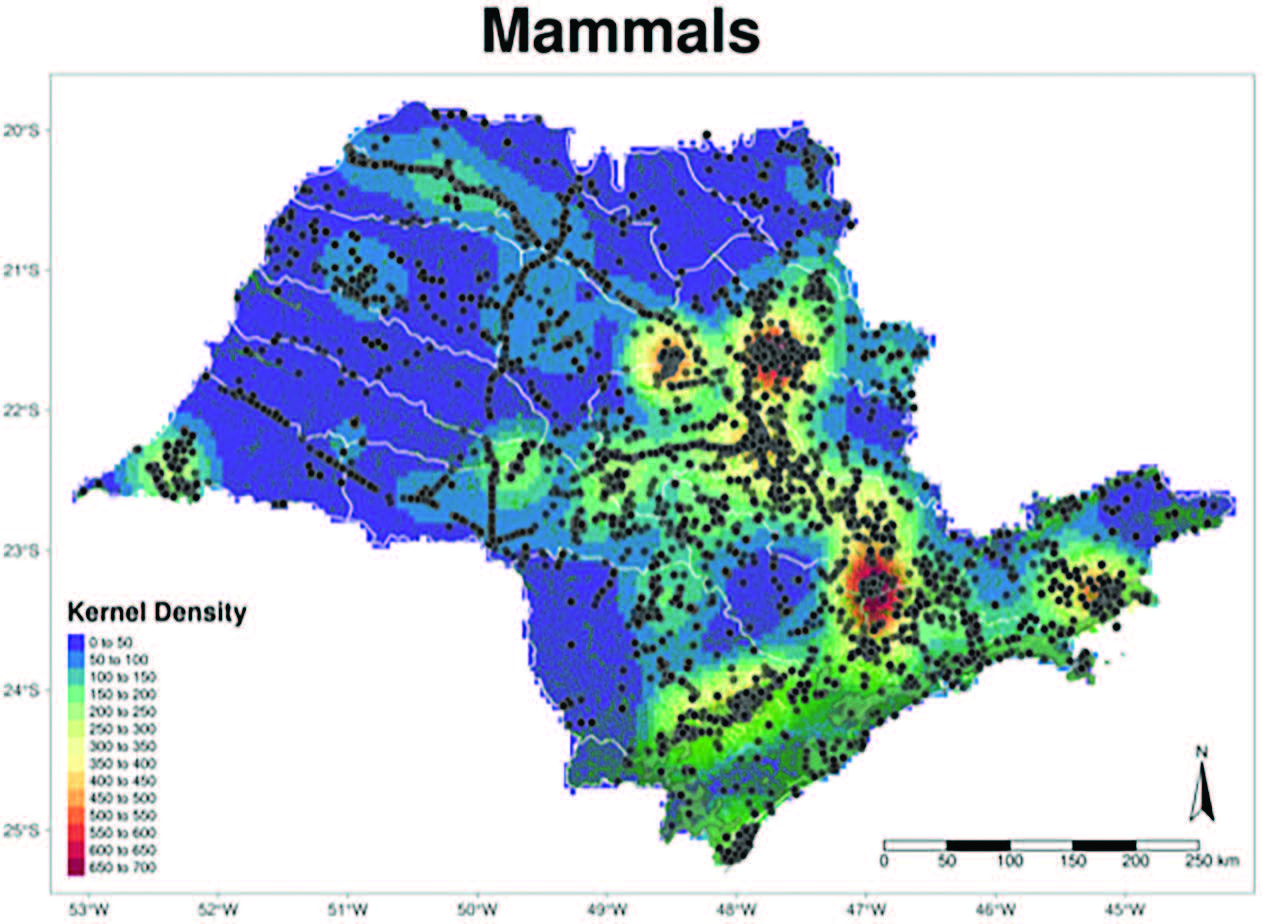

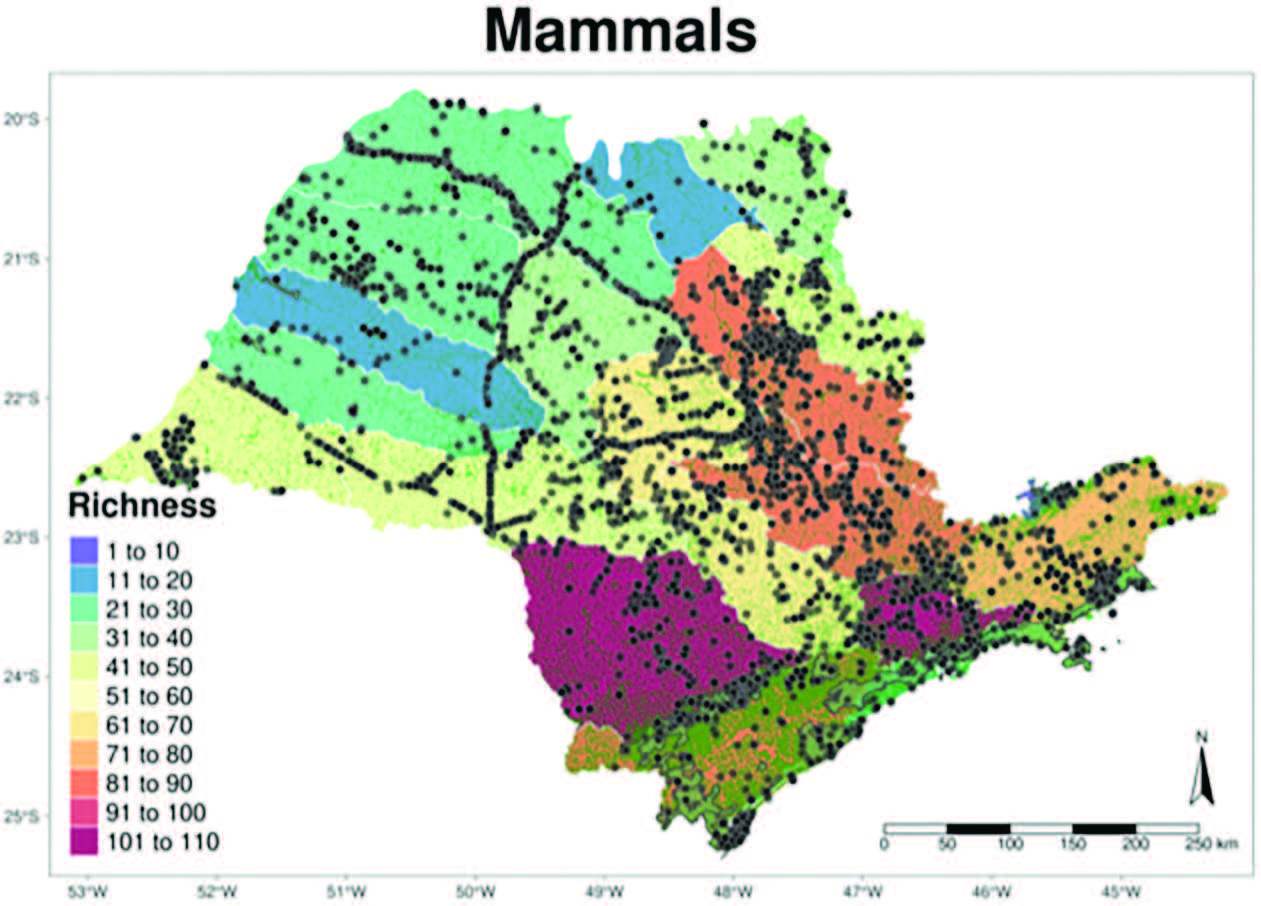

The distribution of records from mammals in São Paulo state shows the areas (red) with the highest number of records. Many records follow roads as the result of roadkill information.

These datasets provided information on 11,037 records, from 173 species. The number of species per Order was: Artiodactyla = 7 species, Carnivora = 23 species, Chiroptera = 48 species, Cingulata = 6 species, Didelphimorphia = 19 species, Lagomorpha = 3 species, Perissodactyla = 1 species, Pilosa = 3 species, Primates = 12 species, and Rodentia = 51 species. The regions of the state with the highest density of records are Parque Estadual Carlos Botelho, Parque Nacional da Serra da Bocaina, Serra do Japi, Área de Relevante Interesse Ecológico Cerrado Pé-de-Gigante, Estação Ecológica de Itirapina, and Parque Estadual do Morro do Diabo. The highest diversity in the humid coastal forests along the Serra do Mar massif and areas of the municipalities of Ribeirão Preto and Jundiaí, mainly associated with the remaining conservation parks, highlighting the role of these forests remnants as maintainers of the state’s local and regional diversity (Figure 3). We created a Github repository with the information we used to generate Figures 2 and 3, as well as the figures in Appendix 2 of supplementary material Supplementary Material The following online material is available for this article: Appendix 1. Checklist of the Mammals from São Paulo State. Appendix 2. Distribution of each mammalian order in São Paulo state. : https://github.com/LEEClab/ms_mammals_sp_spatial_analysis. We also created an interactively spatial repository with the raw data of species records used in this paper, which can be accessed at https://www.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/11273a209cd44bba9826ce689fe04ac9.

Although the distribution of mammals in São Paulo is relatively well studied, an estimate of their population size or abundance is much less known. One of the sites with the best information on population abundance in São Paulo is the Serra do Mar massif (Carlucci et al. 2021CARLUCCI, M. B., V. MARCILIO-SILVA & J. M. TOREZAN. 2021. The southern Atlantic Forest: use, degradation & perspectives for conservation. Pages 91–111. The Atlantic Forest. Springer.), also known as the Serra do Mar Biodiversity Corridor (Corredor de Biodiversidade da Serra do Mar, CBSM), located in the south and southeastern Brazil (Paraná and São Paulo states). CBSM encompasses the largest remaining block of Atlantic Forest (∼16,040 km2), in the slopes and tops of the mountain range of Serra de Paranapiacaba, Serra do Mar, and Serra da Mantiqueira with its adjacent flat lowlands. Some of the largest protected areas in the Atlantic Forest biome are in the CBSM, of which ∼7,276 km2 are under strict protection. Part of these protected areas (State Parks, Ecological Stations, Environmental Protections Areas) is in the Serra de Paranapiacaba, with a 1,200 km2 (Carlucci et al. 2021CARLUCCI, M. B., V. MARCILIO-SILVA & J. M. TOREZAN. 2021. The southern Atlantic Forest: use, degradation & perspectives for conservation. Pages 91–111. The Atlantic Forest. Springer.).

Two main methods have been used to estimate the abundance of medium and large-sized mammals in this region: camera trapping and line-transects (Galetti et al. 2017GALETTI, M., C. R. BROCARDO, R. A. BEGOTTI, L. HORTENCI, F. ROCHA-MENDES, C. S. S. BERNARDO, R. S. BUENO, R. NOBRE, R. S. BOVENDORP, R. M. MARQUES, F. MEIRELLES, S. K. GOBBO, G. BECA, G. SCHMAEDECKE & T. SIQUEIRA. 2017. Defaunation and biomass collapse of mammals in the largest Atlantic forest remnant. Animal Conservation 20:270–281., Ferraz et al. 2022FERRAZ, K. M. P. M. D. B., S. MARCHINI, J. A. BOGONI, R. M. PAOLINO, M. LANDIS, R. FUSCO-COSTA, M. MAGIOLI, L. P. MUNHOES, B. H. SARANHOLI, Y. G. G. RIBEIRO, J. A. D. DOMINI, G. S. MAGEZI, J. C. Z. GEBIN, H. ERMENEGILDO, P. M. GALETTI JUNIOR, M. GALETTI, A. ZIMMERMANN & A. G. CHIARELLO. 2022. Best of both worlds: Combining ecological and social research to inform conservation decisions in a Neotropical biodiversity hotspot. Journal for Nature Conservation 66:126146.). Thirty medium and large-sized native mammal species were sampled by camera-trapping in eight protected areas (49,050 cameras/day; Ferraz et al. 2022, and 53,494 cameras/day; Silveira et al. 2010SILVEIRA, L. F., B. D. M. BEISIEGEL, F. F. CURCIO, P. H. VALDUJO, M. DIXO, V. K. VERDADE, G. M. T. MATTOX & P. T. M. CUNNINGHAM. 2010. Para que servem os inventários de fauna? Estudos avançados 24:173–207., Beisiegel and Nakano-Oliveira 2020BEISIEGEL, B.M. & E. NAKANO-OLIVEIRA. 2020. Histórias de vida e guia fotográfico das onças-pintadas (Panthera onca, Carnivora: Felidae) do Contínuo de Paranapiacaba, São Paulo. Boletim da Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia 87:11–19.), while 44 species were found in 4,090 km line transect in 13 regions along Serra do Mar Corridor (Galetti et al. 2009aGALETTI, M., H. C. GIACOMINI, R. S. BUENO, C. S. BERNARDO, R. M. MARQUES, R. S. BOVENDORP, C. E. STEFFLER, P. RUBIM, S. K. GOBBO & C. I. DONATTI. 2009a. Priority areas for the conservation of Atlantic forest large mammals. Biological Conservation 142:1229–1241., Galetti et al. 2017GALETTI, M., C. R. BROCARDO, R. A. BEGOTTI, L. HORTENCI, F. ROCHA-MENDES, C. S. S. BERNARDO, R. S. BUENO, R. NOBRE, R. S. BOVENDORP, R. M. MARQUES, F. MEIRELLES, S. K. GOBBO, G. BECA, G. SCHMAEDECKE & T. SIQUEIRA. 2017. Defaunation and biomass collapse of mammals in the largest Atlantic forest remnant. Animal Conservation 20:270–281.). The density and biomass of mammals varied 16 and 70-fold among sites and a biomass decline of 98% in sites where hunting is frequent (lowland Atlantic Forest; Galetti et al. 2017GALETTI, M., C. R. BROCARDO, R. A. BEGOTTI, L. HORTENCI, F. ROCHA-MENDES, C. S. S. BERNARDO, R. S. BUENO, R. NOBRE, R. S. BOVENDORP, R. M. MARQUES, F. MEIRELLES, S. K. GOBBO, G. BECA, G. SCHMAEDECKE & T. SIQUEIRA. 2017. Defaunation and biomass collapse of mammals in the largest Atlantic forest remnant. Animal Conservation 20:270–281., Figure 4). The Serra do Mar Corridor holds populations of mammals that are on the verge of extinction in other states’ ecosystems, such as the muriqui (Brachyteles arachnoides) (Jerusalinsky et al. 2011JERUSALINSKY, L., M. TALEBI & F. R. MELO. 2011. Plano de ação nacional para a conservação dos muriquis. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservaçao da Biodiversidade, Brasılia.), the bush dog (Speothos venaticus) (Beisiegel and Ades 2004BEISIEGEL, B. M. & C. ADES. 2004. The bush dog Speothos venaticus (Lund, 1842) at Parque Estadual Carlos Botelho, Southeastern Brazil. Mammalia 68: 65–68.), and the jaguar (Panthera onca) (Beisiegel and Nakano-Oliveira 2020BEISIEGEL, B.M. & E. NAKANO-OLIVEIRA. 2020. Histórias de vida e guia fotográfico das onças-pintadas (Panthera onca, Carnivora: Felidae) do Contínuo de Paranapiacaba, São Paulo. Boletim da Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia 87:11–19.).

Density (ind/km2) of diurnal mammals based in line transects sampling in the Serra do Mar, São Paulo (Sites: IC = Ilha do Cardoso, IB = Ilhabela, CB-H = Carlos Botelho highlands, CB-L = Carlos Botelho Lowlands, IN = Intervales, JU = Jurupará, PT = Petar, CA = Caraguatatuba, CU = Cunha, JR = Juréia, PI = Picinguaba, VG = Vargem Grande (see Galetti et al. 2017GALETTI, M., C. R. BROCARDO, R. A. BEGOTTI, L. HORTENCI, F. ROCHA-MENDES, C. S. S. BERNARDO, R. S. BUENO, R. NOBRE, R. S. BOVENDORP, R. M. MARQUES, F. MEIRELLES, S. K. GOBBO, G. BECA, G. SCHMAEDECKE & T. SIQUEIRA. 2017. Defaunation and biomass collapse of mammals in the largest Atlantic forest remnant. Animal Conservation 20:270–281.).

The population status of mammals in dry forests and Cerrado vegetation is less known, but regions with higher forest cover and connected by forest corridors hold more species than regions with small, isolated fragments immersed in pastures and agriculture fields (Magioli et al. 2015MAGIOLI, M., M. C. RIBEIRO, K. M. P. M. B. FERRAZ & M. G. RODRIGUES. 2015. Thresholds in the relationship between functional diversity and patch size for mammals in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Animal Conservation: 18:499–511., Magioli et al. 2016MAGIOLI, M., K. M. P. M. D. B. FERRAZ, E. Z. F. SETZ, A. R. PERCEQUILLO, M. V. D. S. S. RONDON, V. V. KUHNEN, M. C. D. S. CANHOTO, K. E. A. DOS SANTOS, C. Z. KANDA & G. D. L. FREGONEZI. 2016. Connectivity maintain mammal assemblages functional diversity within agricultural and fragmented landscapes. European Journal of Wildlife Research 62:431–446., Paolino et al. 2018PAOLINO, R. M., J. A. ROYLE, N. F. VERSIANI, T. F. RODRIGUES, N. PASQUALOTTO, V. G. KREPSCHI & A. G. CHIARELLO. 2018. Importance of riparian forest corridors for the ocelot in agricultural landscapes. Journal of Mammalogy 99:874–884., Versiani et al. 2021VERSIANI, N. F., L. L. BAILEY, N. PASQUALOTTO, T. F. RODRIGUES, R. M. PAOLINO, V. ALBERICI & A. G. CHIARELLO. 2021. Protected areas and unpaved roads mediate habitat use of the giant anteater in anthropogenic landscapes. Journal of Mammalogy 102:802–813.). While forest cover and connectivity explain mammal diversity in fragmented landscapes, hunting pressure, and altitude (which is also related to forest productivity) are the main drivers that explain mammal diversity and abundance in large continuous forests of Serra do Mar (Galetti et al. 2009bGALETTI, M., H. C. GIACOMINI, R. S. BUENO, C. S. S. BERNARDO, R. M. MARQUES, R. S. BOVENDORP, C. E. STEFFLER, P. RUBIM, S. K. GOBBO, C. I. DONATTI, R. A. BEGOTTI, F. MEIRELLES, R. D. A. NOBRE, A. G. CHIARELLO & C. A. PERES. 2009b. Priority areas for the conservation of Atlantic forest large mammals. Biological Conservation 142:1229–1241., Ferraz et al. 2022FERRAZ, K. M. P. M. D. B., S. MARCHINI, J. A. BOGONI, R. M. PAOLINO, M. LANDIS, R. FUSCO-COSTA, M. MAGIOLI, L. P. MUNHOES, B. H. SARANHOLI, Y. G. G. RIBEIRO, J. A. D. DOMINI, G. S. MAGEZI, J. C. Z. GEBIN, H. ERMENEGILDO, P. M. GALETTI JUNIOR, M. GALETTI, A. ZIMMERMANN & A. G. CHIARELLO. 2022. Best of both worlds: Combining ecological and social research to inform conservation decisions in a Neotropical biodiversity hotspot. Journal for Nature Conservation 66:126146.). The outbreak of yellow fever in the last few years is likely to have caused the local extinction of howler monkeys in some forest remnants and population decline in many protected areas (Berthet et al. 2021BERTHET, M., G. MESBAHI, G. DUVOT, K. ZUBERBÜHLER, C. CÄSAR & J. C. BICCA-MARQUES. 2021. Dramatic decline in a titi monkey population after the 2016–2018 sylvatic yellow fever outbreak in Brazil. American Journal of Primatology 83:e23335.).

Although São Paulo waters have a high diversity of cetacean species, just six species are residents year-round (20% of the species), four species are seasonal visitors in migration to reproductive areas (13%), two species are random visitors (7%), and 19 were strays from their original distribution (60%) (Figueiredo et al. 2020FIGUEIREDO, G. C., K. B. DO AMARAL & M. C. DE OLIVEIRA SANTOS. 2020. Cetaceans along the southeastern Brazilian coast: occurrence, distribution, and niche inference at local scale. PeerJ 8:e10000.). A resident population of Guiana dolphins, the target of longitudinal investigations since 1995 and with a population estimated at 400 individuals (de Mello et al. 2019DE MELLO, A. B., J. MOLINA, M. KAJIN & M. C. DE O SANTOS. 2019. Abundance Estimates of Guiana Dolphins (Sotalia guianensis; Van Bénéden, 1864) Inhabiting an Estuarine System in Southeastern Brazil. Aquatic Mammals 45.), can be found year-round in the Iguape-Cananeia estuarine waters, at the southern edge of São Paulo state. They can be also found along the shoreline, mainly close to estuarine and riverine discharges. La Plata (Pontoporia blainvillei), Atlantic spotted (Stenella frontalis), Common bottlenose (Tursiops truncatus), and Rough-toothed (Steno bredanensis) dolphins, added to Bryde’s whales (Balaenoptera edeni) are found in relatively high numbers, but data on their abundances are not yet available – the same can be applied to the seasonal visitors. Recent investigations have shown that the coast of São Paulo is a hotspot to investigate La Plata, Atlantic spotted, and Common bottlenose dolphins (Paschoalini and Santos 2020PASCHOALINI, V. U. & M. C. O. SANTOS. 2020. Movements and habitat use of bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus, in south-eastern Brazil. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 100:651–662.).

What are the services and disservices provided by mammals?

Humans have always had a relationship of love and hate with mammals. Humans have domesticated dogs, cats, pigs, sheep, cows, horses, and many other mammal species for pleasure, food, use in transport, and material resources for millennia. At the same time, we were responsible for the extinction of species or local populations that we could not domesticate or that we fear (e.g., predators). In daily life, our urban society sees wildlife mostly in TV documentaries, with a poor understanding of how close and dependent we are on wild mammals. Mammals are known to play important ecosystem services that are hardly acknowledged. For instance, bats eat thousands of tons of insects, preying on at least 237 potential pest species (Ramirez-Francel et al. 2022RAMIREZ-FRANCEL, L. A., L. V. GARCIA-HERRERA, S. LOSADA-PRADO, G. REINOSO-FLOREZ, A. SANCHEZ-HERNANDEZ, S. ESTRADA-VILLEGAS, B. K. LIM & G. GUEVARA. 2022. Bats and their vital ecosystem services: a global review. Integrative Zoology 17:2–23.) in agricultural landscapes, saving >3.7 million USD/year in pest control just in the USA. Bats also pollinate several important crops, such as banana, mango, and guava, and are essential in forest regeneration (Ramirez-Francel et al. 2022RAMIREZ-FRANCEL, L. A., L. V. GARCIA-HERRERA, S. LOSADA-PRADO, G. REINOSO-FLOREZ, A. SANCHEZ-HERNANDEZ, S. ESTRADA-VILLEGAS, B. K. LIM & G. GUEVARA. 2022. Bats and their vital ecosystem services: a global review. Integrative Zoology 17:2–23.). Small, medium, and large mammalian predators play an important role in controlling rodent populations (Cruz et al. 2022CRUZ, L. R., MUYLAERT, R. L., GALETTI, M., & PIRES, M. M. (2022). The geography of diet variation in Neotropical Carnivora. Mammal Review, 52(1): 112–128.).

Mammals also play an important role in seed dispersal and indirectly are important for mitigating human-induced climate change (Bello et al. 2015BELLO, C., M. GALETTI, M. A. PIZO, L. F. MAGNAGO, M. F. ROCHA, R. A. LIMA, C. A. PERES, O. OVASKAINEN & P. JORDANO. 2015. Defaunation affects carbon storage in tropical forests. Sci Adv 1:e1501105., Bello et al. 2021BELLO, C., L. CULOT, C. A. R. AGUDELO & M. GALETTI. 2021. Valuing the economic impacts of seed dispersal loss on voluntary carbon markets. Ecosystem Services 52:101362.). By dispersing large-seeded trees that produce large hardwood trees, with higher carbon storage capacity, large mammals are fundamental for the maintenance of above-ground carbon storage. Large herbivorous mammals (particularly tapirs and white-lipped peccaries) are also important for mediating plant composition and diversity (Villar et al. 2020VILLAR, N., T. SIQUEIRA, V. ZIPPARRO, F. FARAH, G. SCHMAEDECKE, L. HORTENCI, C. R. BROCARDO, P. JORDANO & M. GALETTI. 2020. The cryptic regulation of diversity by functionally complementary large tropical forest herbivores. Journal of Ecology 108:279–290.), plant biomass (Villar et al. 2022VILLAR, N., F. ROCHA-MENDES, R. GUEVARA & M. GALETTI. 2022. Large herbivore-palm interactions modulate the spatial structure of seedling communities and productivity in Neotropical forests. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 20:45–59.), nutrient cycling (Villar et al. 2021VILLAR, N., C. PAZ, V. ZIPPARRO, S. NAZARETH, L. BULASCOSCHI, E. S. BAKKER & M. GALETTI. 2021. Frugivory underpins the nitrogen cycle. Functional Ecology 35:357–368.), and plant life growth form (Souza et al. 2022SOUZA, Y., N. VILLAR, V. ZIPPARRO, S. NAZARETH & M. GALETTI. 2022. Large mammalian herbivores modulate plant growth form diversity in a tropical rainforest. Journal of Ecology 110:845–859.) in the Atlantic Forest. By experimentally fencing part of the vegetation, scientists have found that by feeding or trampling plants, large mammals promote an increase in plant beta diversity (i.e. create a mosaic of areas of low and high diversity) (Villar et al. 2022VILLAR, N., F. ROCHA-MENDES, R. GUEVARA & M. GALETTI. 2022. Large herbivore-palm interactions modulate the spatial structure of seedling communities and productivity in Neotropical forests. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 20:45–59.) and are fundamental in adding carbon and other nutrients to forest’s soil, particularly in areas rich in palms (Euterpe edulis) (Villar et al. 2021VILLAR, N., C. PAZ, V. ZIPPARRO, S. NAZARETH, L. BULASCOSCHI, E. S. BAKKER & M. GALETTI. 2021. Frugivory underpins the nitrogen cycle. Functional Ecology 35:357–368.) (Figure 5). Large mammals are also important in maintaining the diversity of plant growth forms, a vital component of the 3-dimensional diversity of the Atlantic Forest (Souza et al. 2022SOUZA, Y., N. VILLAR, V. ZIPPARRO, S. NAZARETH & M. GALETTI. 2022. Large mammalian herbivores modulate plant growth form diversity in a tropical rainforest. Journal of Ecology 110:845–859.).

Mammals play a fundamental role in carbon and nitrogen soil cycling. Mammal excrements promote fertilization of forest soil and are fundamental for microbes (bacteria, and mycorrhizal fungi) in the soil. The density of palms attracts mammals and creates positive feedback on soil fertilization due to mammal foraging (from Villar et al. 2021VILLAR, N., C. PAZ, V. ZIPPARRO, S. NAZARETH, L. BULASCOSCHI, E. S. BAKKER & M. GALETTI. 2021. Frugivory underpins the nitrogen cycle. Functional Ecology 35:357–368.).

Nevertheless, mammals can play disservices and cause major economic loss when overabundant, particularly in the transmission of zoonoses (Keesing et al. 2010KEESING, F., L. K. BELDEN, P. DASZAK, A. DOBSON, C. D. HARVELL, R. D. HOLT, P. HUDSON, A. JOLLES, K. E. JONES, C. E. MITCHELL, S. S. MYERS, T. BOGICH & R. S. OSTFELD. 2010. Impacts of biodiversity on the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases. Nature 468:647–652., Luz et al. 2019LUZ, H. R., F. B. COSTA, H. R. BENATTI, V. N. RAMOS, M. C. DE A. SERPA, T. F. MARTINS, I. C. ACOSTA, D. G. RAMIREZ, S. MUÑOZ-LEAL & A. RAMIREZ-HERNANDEZ. 2019. Epidemiology of capybara-associated Brazilian spotted fever. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 13:e0007734.) or when feeding on agricultural crops (Ferraz et al. 2003FERRAZ, K. M. P. M. D., M.-A. LECHEVALIER, H. T. Z. D. COUTO & L. M. VERDADE. 2003. Damage caused by capybaras in a corn field. Scientia Agricola 60:191–194.) or predation on livestock (Palmeira et al. 2015PALMEIRA, F. B. L., C. T. TRINCA & C. M. HADDAD. 2015. Livestock Predation by Puma (Puma concolor) in the Highlands of a Southeastern Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Environmental Management 56:903–915.). An estimate of 40,000 viruses occurs in the bodies of mammals, of which a quarter could conceivably infect humans; and climate change associated with habitat loss will continue to force many species to relocate to habitats near humans, increasing the chances of virus spillover into humans (Carlson et al. 2022CARLSON, C.J., ALBERY, G.F., MEROW, C. et al. 2022. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/...

, Winck et al. 2022WINCK, G.R., RAIMUNDO, R.L.G., FERNANDES-FERREIRA, H., BUENO, M.G., D’ANDREA, P.S., ROCHA, F.L., CRUZ, G.L.T., VILAR, E.M., BRANDÃO, M., CORDEIRO, J.L.P., ANDREAZZI, C.S., 2022. Socioecological vulnerability and the risk of zoonotic disease emergence in Brazil. Science Advances 8: eabo5774.). The intense monoculture of sugar cane has facilitated the expansion and population growth of the introduced wild boars (javali or javaporco) whose 70% of their diet is composed of corn or sugar cane (Pedrosa et al. 2021PEDROSA, F., W. BERCÊ, V. E. COSTA, T. LEVI & M. GALETTI. 2021. Diet of invasive wild pigs in a landscape dominated by sugar cane plantations. Journal of Mammalogy 102:1309–1317.). The increase in wild boar populations may lead to an increase in rabies cases because they are today the main prey of vampire bats (Galetti et al. 2016GALETTI, M., F. PEDROSA, A. KEUROGHLIAN & I. SAZIMA. 2016. Liquid lunch–vampire bats feed on invasive feral pigs and other ungulates. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14:505–506., Goncalves et al. 2021GONCALVES, F., M. GALETTI & D. G. STREICKER. 2021. Management of vampire bats and rabies: a precaution for rewilding projects in the Neotropics. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 19:37–42.).

How do mammals survive in a human-modified landscape?

There has been a common misunderstanding that most of the mammal species that we see in agricultural landscapes are exotic species such as livestock (cow, horse, pigs) or invasive species, such as European hares (Lepus europaeus; Pasqualotto et al. 2021PASQUALOTTO, N., D. BOSCOLO, N. F. VERSIANI, R. M. PAOLINO, T. F. RODRIGUES, V. G. KREPSCHI & A. G. CHIARELLO. 2021. Niche opportunity created by land cover change is driving the European hare invasion in the Neotropics. Biological Invasions 23:7–24.) and wild pigs (Sus scrofa; Pedrosa et al. 2015PEDROSA, F., R. SALERNO, F. V. B. PADILHA & M. GALETTI. 2015. Current distribution of invasive feral pigs in Brazil: economic impacts and ecological uncertainty. Natureza & Conservacao 13:84–87.). Recent evidence has shown that even largely human-modified landscapes dominated by agriculture and pastures hold a considerable diversity of native mammals (Magioli et al. 2016, Beca et al. 2017BECA, G., M. H. VANCINE, C. S. CARVALHO, F. PEDROSA, R. S. C. ALVES, D. BUSCARIOL, C. A. PERES, M. C. RIBEIRO & M. GALETTI. 2017. High mammal species turnover in forest patches immersed in biofuel plantations. Biological Conservation 210:352–359.). How species persist, and even thrive, in human-modified ecosystems is becoming a recurrent question in ecology.

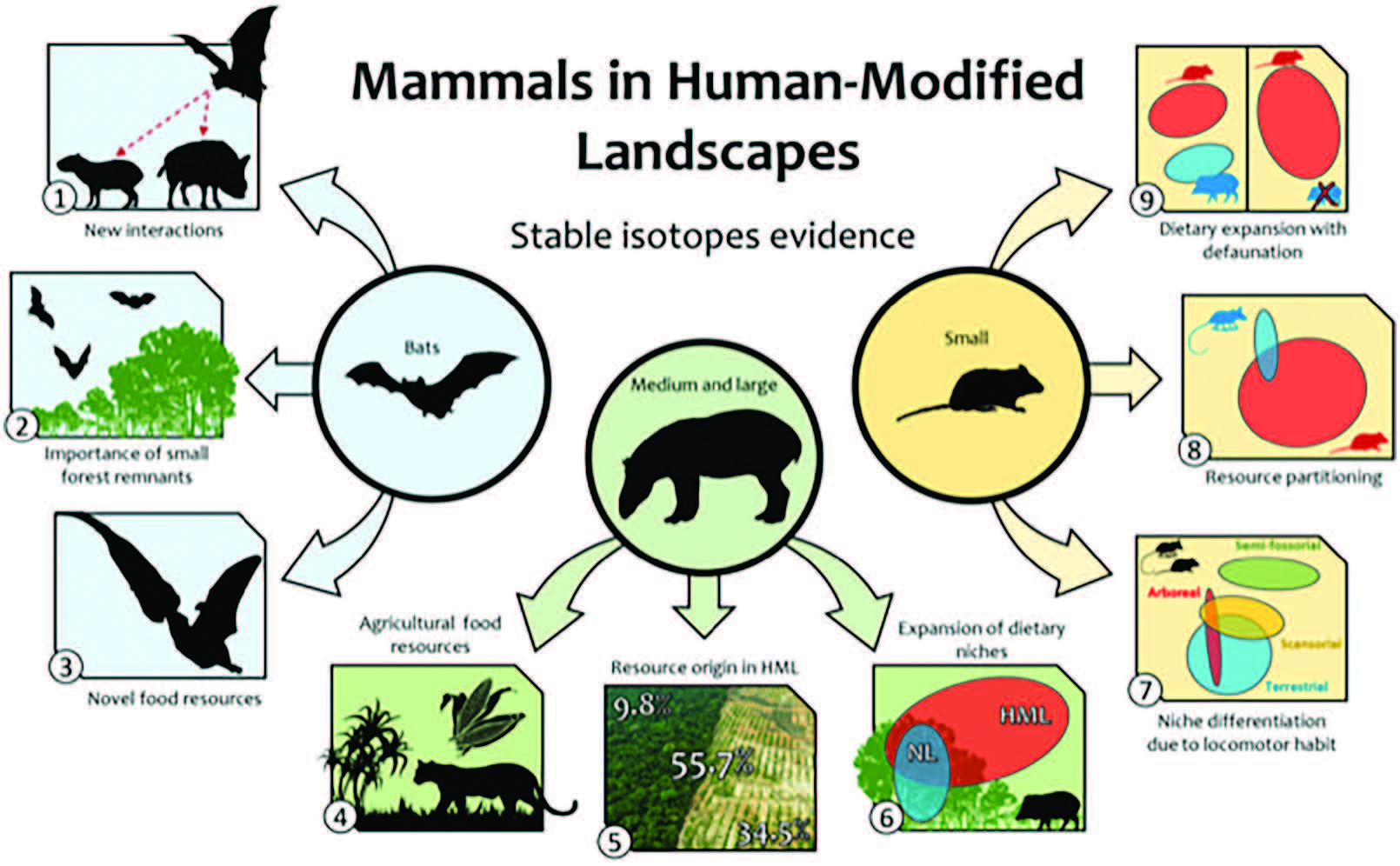

Several studies have found that medium and large mammals are coping with land-use modification by changing their feeding behavior and incorporating resources from agricultural crops. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes analysis found that mammals are incorporating more agricultural crops (C4-rich resources, such as corn) and nitrogen-rich food items (probably due to the intense crop fertilization) when forest resources are scarce (Magioli et al. 2014MAGIOLI, M., M. Z. MOREIRA, K. M. B. FERRAZ, R. A. MIOTTO, P. B. CAMARGO, M. G. RODRIGUES, M. C. SILVA CANHOTO & E. F. SETZ. 2014. Stable isotope evidence of Puma concolor (Felidae) feeding patterns in agricultural landscapes in southeastern Brazil. Biotropica 46:451–460., Magioli et al. 2019MAGIOLI, M., M. Z. MOREIRA, R. C. B. FONSECA, M. C. RIBEIRO, M. G. RODRIGUES & K. M. P. M. DE BARROS. 2019. Human-modified landscapes alter mammal resource and habitat use and trophic structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116:18466–18472., Magioli et al. 2022MAGIOLI, M., N. VILLAR, M. L. JORGE, C. BIONDO, A. KEUROGHLIAN, J. BRADHAM, F. PEDROSA, V. COSTA, M. Z. MOREIRA & K. M. P. M. D. B. FERRAZ. 2022. Dietary expansion facilitates the persistence of a large frugivore in fragmented tropical forests. Animal Conservation., Pedrosa et al. 2021PEDROSA, F., W. BERCÊ, V. E. COSTA, T. LEVI & M. GALETTI. 2021. Diet of invasive wild pigs in a landscape dominated by sugar cane plantations. Journal of Mammalogy 102:1309–1317.). The analyses of stable isotopes have provided important evidence of the plasticity of mammals in human-dominated landscapes and in continuous forests where defaunation has modified trophic food webs (Galetti et al. 2015GALETTI, M., R. GUEVARA, C. L. NEVES, R. R. RODARTE, R. S. BOVENDORP, M. MOREIRA, J. B. HOPKINS & J. D. YEAKEL. 2015. Defaunation affect population and diet of rodents in Neotropical rainforests. Biological Conservation 190:2–7., Gonçalves et al. 2020GONÇALVES, F., M. MAGIOLI, R. S. BOVENDORP, K. M. FERRAZ, L. BULASCOSCHI, M. Z. MOREIRA & M. GALETTI. 2020. Prey choice of introduced species by the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) on an Atlantic Forest land-bridge island. Acta Chiropterologica 22:167–174.) (Figure 6).

The use of stable isotopes has elucidated how mammals are thriving in human-modified landscapes 1) Galetti et al. (2016b) and Gonçalves et al. (2020GONÇALVES, F., M. MAGIOLI, R. S. BOVENDORP, K. M. FERRAZ, L. BULASCOSCHI, M. Z. MOREIRA & M. GALETTI. 2020. Prey choice of introduced species by the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) on an Atlantic Forest land-bridge island. Acta Chiropterologica 22:167–174.); 2) Kruszynski et al. (2022); 3) Kruszynski et al. (2016); 4) Magioli et al. (2014MAGIOLI, M., M. Z. MOREIRA, K. M. B. FERRAZ, R. A. MIOTTO, P. B. CAMARGO, M. G. RODRIGUES, M. C. SILVA CANHOTO & E. F. SETZ. 2014. Stable isotope evidence of Puma concolor (Felidae) feeding patterns in agricultural landscapes in southeastern Brazil. Biotropica 46:451–460.); 5) Magioli et al. (2019MAGIOLI, M., M. Z. MOREIRA, R. C. B. FONSECA, M. C. RIBEIRO, M. G. RODRIGUES & K. M. P. M. DE BARROS. 2019. Human-modified landscapes alter mammal resource and habitat use and trophic structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116:18466–18472.); 6) Magioli et al. (2022MAGIOLI, M., N. VILLAR, M. L. JORGE, C. BIONDO, A. KEUROGHLIAN, J. BRADHAM, F. PEDROSA, V. COSTA, M. Z. MOREIRA & K. M. P. M. D. B. FERRAZ. 2022. Dietary expansion facilitates the persistence of a large frugivore in fragmented tropical forests. Animal Conservation.); 7) and 8) Galetti et al. (2016a) and Bovendorp et al. (2017); 9) Galetti et al. (2015GALETTI, M., R. GUEVARA, C. L. NEVES, R. R. RODARTE, R. S. BOVENDORP, M. MOREIRA, J. B. HOPKINS & J. D. YEAKEL. 2015. Defaunation affect population and diet of rodents in Neotropical rainforests. Biological Conservation 190:2–7.). Ellipses in panels 6–9 represent the bidimensional isotopic niche space of stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes; HML = human-modified landscape; NL = natural landscape.

Habitat degradation, overfishing, noise and chemical pollution, incidental captures in fishing operations, collisions with boats and the lack of a national and a regional policy to protect cetaceans are the main threats to their survival along the coast of São Paulo (Santos et al., 2010SANTOS, M. C. de O.; SICILIANO, S.; VICENTE, A. F. C.; ALVARENGA, F. S.; ZAMPIROLLI, E.; SOUZA, S. P. & MARANHO, A. 2010. Cetacean records along São Paulo state coast, Southeastern Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Oceanography, 58:123–142.; Figueiredo et al. 2017). The larger port in Latin America, added to the largest oil plant on land in Brazil, and the increase in a 3-order in the number of leisure boats in the past two decades (CODESP, 1992; Zanardi-Lamardo et al. 2013; Figueiredo et al. 2017) are responsible for an extremely high boat and ship traffic, posing cetaceans at risk. The number of the southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) visits has been decreasing over the last four decades (Santos et al. 2001; Figueiredo et al. 2017), meanwhile, its population abundance has been growing in the southern hemisphere (Cooke & Zerbini, 2018). The way resident cetaceans and seasonal visitors are reacting to the quoted impacts should be urgently addressed.

The occurrence of a high diversity of mammals in human-modified landscapes does not mean that they are healthy. Recent studies on terrestrial and marine mammals have found high contamination by pesticides and other toxic chemicals in mammalian populations (Yogui et al. 2010YOGUI, G. T., M. C. O. SANTOS, C. P. BERTOZZI & R. C. MONTONE. 2010. Levels of persistent organic pollutants and residual pattern of DDTs in small cetaceans from the coast of São Paulo, Brazil. Marine Pollution Bulletin 60:1862–1867., Medici et al. 2014MEDICI, E. P., P. R. MANGINI & R. C. FERNANDES-SANTOS. 2014. Health assessment of wild lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris) populations in the Atlantic forest and Pantanal biomes, Brazil (1996–2012). Journal of Wildlife Diseases 50:817–828.).

What is the future of mammal diversity in São Paulo State?

São Paulo state has the paradox of having the largest human population in Brazil, the largest road network, and the largest industrial section, but also has the largest remnants of the Atlantic Forest in Brazil. In the last 10 years, forest coverage in São Paulo State increased 5% thanks to the State Restoration Program, Sustainable Agricultural Program, and increasing investment in law enforcement, but we need a more audacious environmental agenda to avoid the extinction of the endemic species, avoid the extirpation of large-sized species that have lost their habitats (Marsh deer, Pampas deer) or species that are continuously being persecuted (Jaguars), control invasive species (particularly the wild boar) and promote the persistence and the connectivity of mammal populations in the much-altered landscapes of São Paulo.

Although the intensive studies in the last two decades have provided an immense bulk of information about the mammals in São Paulo, there are many regions that are poorly sampled. In addition to traditional surveys, the use of new technologies such as the environmental DNA (eDNA) or ingesta or invertebrate-derived DNA (iDNA) can also be a powerful tool for assessing vertebrate (mammal) communities (Carvalho et al. 2021CARVALHO, C. S., M. E. DE OLIVEIRA, K. G. RODRIGUEZ-CASTRO, B. H. SARANHOLI & P. M. GALETTI JR. 2021. Efficiency of eDNA and iDNA in assessing vertebrate diversity and its abundance. Molecular Ecology Resources.).

About 15% of the mammal species are threatened by extirpation, and six have already disappeared in the state (two marsupials, the giant otter, the giant armadillo, the Pampas deer, and the Brazilian dwarf brocket deer) and at least two large-sized species are on the verge of state’s extirpation (Jaguar, Marsh deer). All four state’s endemic species are not safe from extinction. For example, the Black lion tamarin Leontopithecus chrysopygus survives in 15 localities in the state of São Paulo, but only the subpopulation of the Morro do Diabo State Park, with 1,200 individuals, has been considered demographically and genetically viable in the long term (Rezende et al. 2020REZENDE, G., C. KNOGGE, F. PASSOS, G. LUDWIG, L. OLIVEIRA, L. JERUSALINSKY & R. MITTERMEIER. 2020. Leontopithecus chrysopygus. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2020: e. T11505A17935400.). Nevertheless, the species occurs in high densities in the degraded riverine forest in the upper Paranapanema watershed, including eucalyptus plantations where the understory was allowed to regenerate (as in Buri municipality). The restoration of larger areas of riverine forest and legal reserves connecting areas such as Capão Bonito National Forest and forest fragments in the municipalities of Buri and São Miguel Arcanjo would greatly increase the resilience of the species (Garcia et al. 2022GARCIA, F. D. O., L. CULOT, R. E. W. F. DE CARVALHO & V. J. ROCHA. 2022. Functionality of two canopy bridge designs: successful trials for the endangered black lion tamarin and other arboreal species. European Journal of Wildlife Research 68:1–14.). The Giant Atlantic Tree Rat Phyllomys thomasi is endemic to São Sebastião island (Ilhabela) with no individuals in captivity. The status of this species is unknown (Olmos 1997OLMOS, F. 1997. The giant Atlantic Forest tree rat Nelomys thomasi (Echimyidae): A Brazilian insular endemic. Mammalia 61:130–134.), but recent records have been made in secondary forests in low-elevation areas (F. Olmos pers. obs.). Most of the island is part of a state park, except areas below 100 m asl where a rapid urbanization process is occurring. The protection of the low-elevation (sea-level to 100 m asl) belt from Saco do Sombrio to Castelhanos, Caveira, and Poço beaches, either by adding it to Ilhabela State Park or by creating a new protected area, would include areas where P. thomasi have been recorded.

Cerrado species, especially those from open savannas (campo limpo, campo cerrado), are particularly vulnerable to local extinction because most of the protected areas are too small and poorly managed. In the absence of controlled fires and herbivory, many open savannas are becoming dominated by trees (transitioning into cerradão), a phenomenon known as the “wood encroachment” (Stevens et al. 2017STEVENS, N., C. E. LEHMANN, B. P. MURPHY & G. DURIGAN. 2017. Savanna woody encroachment is widespread across three continents. Global Change Biology 23:235–244.). Specialists in open savannas such as the Pampas Deer, Marsh Deer, and the rodents Clyomys laticeps, Cerradomys scotti, and marsupials such as Cryptonanus chacoensis are negatively affected by increasing wood encroachment (Furtado et al. 2021FURTADO, L. O., G. R. FELICIO, P. R. LEMOS, A. V. CHRISTIANINI, M. MARTINS & A. P. CARMIGNOTTO. 2021. Winners and Losers: How Woody Encroachment Is Changing the Small Mammal Community Structure in a Neotropical Savanna. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9.).

Some large-bodied species are on the verge of extinction due to illegal hunting, including the Jaguar (Panthera onca), which also suffers from competition with humans for its favored prey (peccaries). Recent estimates suggest that less than 50 jaguars live in São Paulo state, distributed in only two isolated populations (Paviolo et al. 2016PAVIOLO, A., C. DE ANGELO, K. M. FERRAZ, R. G. MORATO, J. M. PARDO, A. C. SRBEK-ARAUJO, B. DE MELLO BEISIEGEL, F. LIMA, D. SANA, M. X. DA SILVA et al. 2016. A biodiversity hotspot losing its top predator: The challenge of jaguar conservation in the Atlantic Forest of South America. Scientific Reports 6.). The conservation of this species will require the reestablishment of healthy populations of prey species such as peccaries in the Atlantic Forest, increasing the likelihood of suitable habitat being colonized and the translocation of individuals from other populations. The conservation of Jaguars (and many other species) would be greatly enhanced if broad forest corridors more in line with scientific recommendations, than the meager belts required by the Forest Code, are created along the shores of the reservoirs that now make up most of the Paraná, Paranapanema, Tietê and Grande rivers.

The situation of most deer species in São Paulo state is worrisome. The Marsh deer is critically endangered in the state with only two natural sub-populations (Rio do Peixe and Rio Aguapeí) and one introduced (Rio Mogi-Guaçu) and probably less than 200 individuals left in the wild (Duarte et al. 2012DUARTE, J. M. B., U. PIOVEZAN, E. DOS SANTOS ZANETTI, H. G. DA CUNHA RAMOS, L. M. TIEPOLO, A. VOGLIOTI, M. L. DE OLIVEIRA, L. F. RODRIGUES & L. B. DE ALMEIDA. 2012. Avaliação do risco de extinção do cervo-do-Pantanal Blastocerus dichotomus Illiger, 1815, no Brasil. Biodiversidade Brasileira-BioBrasil:3–14.). The Brazilian dwarf brocket deer (Mazama nana) is likely to be one of the extirpated species in the state, the small brocket deer (Mazama jucunda, formerly M. bororo) vulnerable and Mazama rufa, a recently revalidated species, is likely to be critically endangered (Peres et al. 2022; M.B.Duarte, unpublished data).

While some species are declining, other species seem to be expanding in the state, particularly carnivore-generalist species, such as the maned-wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus; Coelho et al. 2018COELHO, L., D. ROMERO, D. QUEIROLO & J. C. GUERRERO. 2018. Understanding factors affecting the distribution of the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) in South America: spatial dynamics and environmental drivers. Mammalian Biology 92:54–61.), the Pampas fox (Lycalopex gymnocercus; Magioli et al. 2016), the brown brocket deer (Mazama gouazoubira; Duarte et al. 2012DUARTE, J. M. B., U. PIOVEZAN, E. DOS SANTOS ZANETTI, H. G. DA CUNHA RAMOS, L. M. TIEPOLO, A. VOGLIOTI, M. L. DE OLIVEIRA, L. F. RODRIGUES & L. B. DE ALMEIDA. 2012. Avaliação do risco de extinção do cervo-do-Pantanal Blastocerus dichotomus Illiger, 1815, no Brasil. Biodiversidade Brasileira-BioBrasil:3–14.) and the Pantanal cat (now Leopardus braccatus; Breviglieri et al. 2018BREVIGLIERI, C. P. B., M. C. CASTRO, D. C. RIBEIRO, L. DE OLIVEIRA, J. H. P. DIAS & F. C. MONTEFELTRO. 2018. First confirmed records of the Pantanal Cat, Leopardus colocola braccatus (Cope, 1889), in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Check List 14:699.). All these species are taking the opportunity of the previously forested areas being transformed into savanna-like environments, represented mostly by anthropogenic land-cover types, a phenomenon named “fauna savanization” (Sales et al. 2020SALES, L. P., M. GALETTI & M. M. PIRES. 2020. Climate and land-use change will lead to a faunal “savannization” on tropical rainforests. Glob Chang Biol 26:7036–7044.). Generalist rodent species (e.g. Akodon montensis, Oligoryzomys nigripes) are other species that are rapidly increasing in the state (Umetsu and Pardini 2007UMETSU, F. & R. PARDINI. 2007. Small mammals in a mosaic of forest remnants and anthropogenic habitats-evaluating matrix quality in an Atlantic forest landscape. Landscape Ecology 22:517–530.). In addition, anthropogenic land use is also benefiting the invasion of exotics, such as the wild boar and the European hare (Pedrosa et al. 2015PEDROSA, F., R. SALERNO, F. V. B. PADILHA & M. GALETTI. 2015. Current distribution of invasive feral pigs in Brazil: economic impacts and ecological uncertainty. Natureza & Conservacao 13:84–87., Pasqualotto et al. 2021PASQUALOTTO, N., D. BOSCOLO, N. F. VERSIANI, R. M. PAOLINO, T. F. RODRIGUES, V. G. KREPSCHI & A. G. CHIARELLO. 2021. Niche opportunity created by land cover change is driving the European hare invasion in the Neotropics. Biological Invasions 23:7–24.). What we know is that this expansion of some species is not due to long movements from populations from more pristine Cerrado. For instance, the Maned wolves of São Paulo are genetically differentiated from the western Mato Grosso do Sul populations and show reduced genetic variation, probably caused by the extensive landscape modifications across the São Paulo state (Rodriguez-Castro et al. 2022RODRIGUEZ-CASTRO, K. G., F. G. LEMOS, F. C. AZVEDO, M. C. FREITAS-JUNIOR, A. L. J. DESBIEZ & J. P. M. GALETTI. 2022. Human highly modified landscapes restrict gene flow of the largest neotropical canid, the maned wolf. Biodiversity and Conservation.).

Most of the native vegetation or recovering areas in the Atlantic Forest region are in areas occupied formerly by savanna or semideciduous forests and we need to create new ways to protect the remaining forest patches without burdening agricultural lands. Focusing on the restoration and promoting connectivity between patches of riparian forest in the savanna area is crucial to maintaining the movement of mammals and restoring their genetic diversity (Saranholi et al. 2017SARANHOLI, B. H., K. CHÁVEZ-CONGRAINS & P. M. GALETTI. 2017. Evidence of recent fine-scale population structuring in south American Puma concolor. Diversity 9:44., Saranholi et al. 2022SARANHOLI, B. H., A. SANCHES, J. F. M. RAMÍREZ, C. D. S. CARVALHO, M. GALETTI & P. M. GALETTI JR. 2022. Long-term persistence of the large mammal lowland tapir is at risk in the largest Atlantic forest corridor. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation:00–00.). Some important remnants in the Cerrado and semideciduous forests deserve priority of conservation because they maintain several endangered species and can act as source individuals for the smaller fragments nearby (e.g., Fazenda Barreiro Rico/Bacury) (Antunes and Eston 2009ANTUNES, A. Z. & M. R. ESTON. 2009. Mamíferos (Chordata: Mammalia) florestais de médio e grande porte registrados em Barreiro Rico, Anhembi, Estado de São Paulo. Revista do Instituto Florestal 21:201–215., Beca et al. 2017BECA, G., M. H. VANCINE, C. S. CARVALHO, F. PEDROSA, R. S. C. ALVES, D. BUSCARIOL, C. A. PERES, M. C. RIBEIRO & M. GALETTI. 2017. High mammal species turnover in forest patches immersed in biofuel plantations. Biological Conservation 210:352–359.).

The coexistence between humans and wild mammals requires an integrative social and ecological agenda focusing on turning ‘conflicts’ into win-win solutions. Hunting, animal-vehicle collisions, and the spillover of zoonotic disease are among the conflicts most challenging for the São Paulo state. For instance, about 40,000 individuals of medium and large-sized mammals are road-killed per year on highways in the state of São Paulo affecting at least 33 different species (Abra et al. 2021ABRA, F. D., HUIJSER, M. P., MAGIOLI, M., BOVO, A. A. A., & de BARROS, K. M. P. M. 2021. An estimate of wild mammal roadkill in São Paulo state, Brazil. Heliyon, 7(1), e06015.). Road mortality can be considered one of the most important mortality risks, overtaking poaching, animal trafficking, and big fires (Galetti et al. 2021GALETTI, M., F. GONÇALVES, N. VILLAR, V. B. ZIPPARRO, C. PAZ, C. MENDES, L. LAUTENSCHLAGER, Y. SOUZA, P. AKKAWI & F. PEDROSA. 2021. Causes and consequences of large-scale defaunation in the Atlantic forest. Pages 297–324. The Atlantic Forest. Springer.). In São Paulo state, about 156 Maned wolves, 149 Giant anteaters, and 47 Pumas are road-killed per year (Abra et al. 2021ABRA, F. D., HUIJSER, M. P., MAGIOLI, M., BOVO, A. A. A., & de BARROS, K. M. P. M. 2021. An estimate of wild mammal roadkill in São Paulo state, Brazil. Heliyon, 7(1), e06015.). Collisions with animals on highways in São Paulo state represent 3% of all collisions, totaling more than 2,600 animal-vehicle crashes per year, of which 18.5% of these resulted in human injuries or fatalities. The losses that include material, aesthetic, moral damages, and health treatments from human victims burden São Paulo society with 56 million reais annually (or 12 million US dollars) (Abra et al. 2019ABRA, F. D., B. M. GRANZIERA, M. P. HUIJSER, K. M. P. M. D. B. FERRAZ, C. M. HADDAD & R. M. PAOLINO. 2019. Pay or prevent? Human safety, costs to society and legal perspectives on animal-vehicle collisions in São Paulo state, Brazil. Plos One 14:e0215152.).

Hunting (particularly wild boars), a common practice in São Paulo state, can increase the spillover of zoonoses to humans (Winck et al. 2022WINCK, G.R., RAIMUNDO, R.L.G., FERNANDES-FERREIRA, H., BUENO, M.G., D’ANDREA, P.S., ROCHA, F.L., CRUZ, G.L.T., VILAR, E.M., BRANDÃO, M., CORDEIRO, J.L.P., ANDREAZZI, C.S., 2022. Socioecological vulnerability and the risk of zoonotic disease emergence in Brazil. Science Advances 8: eabo5774.). Potential new diseases may emerge and re-emerge from wild and invasive mammals, as they carry thousands of known and unknown viruses (Holmes 2022HOLMES, E. C. 2022. COVID-19—lessons for zoonotic disease. American Association for the Advancement of Science.). Wild boars, for instance, may host dozens of viruses and bacteria and are one of the main preys of vampire bats (Schneider et al. 2009SCHNEIDER, M. C., P. C. ROMIJN, W. UIEDA, H. TAMAYO, D. F. D. SILVA, A. BELOTTO, J. B. D. SILVA & L. F. LEANES. 2009. Rabies transmitted by vampire bats to humans: an emerging zoonotic disease in Latin America? Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 25:260–269., Stoner-Duncan et al. 2014STONER-DUNCAN, B., D. G. STREICKER & C. M. TEDESCHI. 2014. Vampire bats and rabies: toward an ecological solution to a public health problem. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 8:e2867., Galetti et al. 2016GALETTI, M., F. PEDROSA, A. KEUROGHLIAN & I. SAZIMA. 2016. Liquid lunch–vampire bats feed on invasive feral pigs and other ungulates. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14:505–506.). Illegal hunting can only be controlled by equipped park rangers in the protected areas and the adequate management of invasive species should be done by professional wildlife managers, not armed civilians.

Most of the protected parks in the state are badly understaffed, and hunting and palm-heart harvesting negatively impact several species (Valverde et al. 2021VALVERDE, J., C. D. S. CARVALHO, P. JORDANO & M. GALETTI. 2021. Large herbivores regulate the spatial recruitment of a hyperdominant Neotropical palm. Biotropica 53:286–295.). Ecotourism is an obvious strategy to help protect those areas, create jobs, and develop a sustainable economy based on having positive (non-lethal) experiences with wildlife the way many developing countries, from bird-watching hub Costa Rica to gorilla-haven Rwanda, have managed. Despite decades-old, positive experiences in Intervales State Park such as being one of the biggest consumer markets of bird watchers and wildlife photographers in the country, most protected areas in São Paulo still lack proper ecotourism programs that look at wildlife as an economic asset. Better infrastructure and security, standard rules across the protected area system, partnerships with local businesses, granting tourism concessions, training for local guides and rangers, and start-ups that ally conservation to economic viability is major gaps, only partially filled by private enterprises such as the ones taking enthusiasts to watch Black Lion Tamarins in Buri, Muriquis in Carlos Botelho State Park and São Francisco Xavier and Tapirs in São Miguel Arcanjo and Tapiraí municipalities.

The state of São Paulo has started a payment of ecological services program and is planning to scale it up in the coming years, including bonuses to those preventing human-wildlife conflicts. This policy has the potential of reducing retaliatory killing and may contribute to the conservation of the Jaguar. Using schemes based on payments for environmental services and carbon markets to restore large areas currently occupied by the degraded pasture of low economic output in the Paraíba river valley, the interior slopes of the Serra do Mar, and lower areas of the Mantiqueira range would not only increase the available habitat to many mammalian species and connect currently isolated populations but also increase the resilience of watersheds that supply water to a large percentage of the Brazilian population. Therefore, the conservation of the mammalian diversity in São Paulo relies on strategies that connect forests within São Paulo and between São Paulo and neighboring states, curb illegal hunting, control invasive wild boar, create green roads, and provide incentives for ecotourism.

Supplementary Material

The following online material is available for this article:

Appendix 1. Checklist of the Mammals from São Paulo State.

Appendix 2. Distribution of each mammalian order in São Paulo state.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to the underpaid rangers, park administration staff, and researchers from Instituto and Fundação Florestal do Estado de São Paulo who are the guardians of the state’s biodiversity. The Biota FAPESP Program was essential for the development of the information compiled here. This collaboration was made possible by the diverse grants from FAPESP (2014/01986-0, 2014/09300-0, 2014/10192-7, 2018/16662-6, 2018/50038-8). APC thanks FAPESP (2011/20022-3; 2015/21259-8; 2018/14091-1; 2020/12658-4) and CNPq (484346/2011-3); MCR thanks FAPESP (2013/50421-2; 2020/01779-5; 2021/08534-0; 2021/10195-0) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq (442147/2020-1; 402765/2021-4; 313016/2021-6) for their financial support. KMPMBF thanks National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq (308632/2018-4 and 303940/2021-2) and Fundação Grupo Boticário (1001_20141 and 1097_20171). MCOS thanks FAPESP (2010/51323-6; 2011/515543-9) and CNPq (308331/2010-9; 311396/2020-8). AGC thanks CNPq (303101/2017-2 and 308660/2021-8) and FAPESP (2011/22449-4 and 2016/19106-1). MHV thanks Capes doctoral scholarship (88887.513979/2020-00). We also thank Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) for the scholarship granted to MM. PMGJ thanks FAPESP (2010/52315-7, 2013/19377-7, 2017/23548-2) and CNPq (563299/2010-0, 303524/2019-7). BMB thanks FAPESP (2008/03099-0, 2019/20525-7) and Fundação o Boticário de Proteção à Natureza (0683/20052). MG is supported by CNPq (300970/2015-3) and FAPESP (2014/01986-0). RLM was supported by FAPESP (2012/04096-0, 2015/17739-4) and Bryce Carmine and Anne Carmine (née Percival) through the Massey University Foundation. We thank Instituto Florestal and Fundação Florestal do Estado de São Paulo for the permission to work in their administrative parks.

-

EthicsThis study did not involve human beings and or clinical trials that should be approved by one Institutional Committee.

References

- ABRA, F. D., B. M. GRANZIERA, M. P. HUIJSER, K. M. P. M. D. B. FERRAZ, C. M. HADDAD & R. M. PAOLINO. 2019. Pay or prevent? Human safety, costs to society and legal perspectives on animal-vehicle collisions in São Paulo state, Brazil. Plos One 14:e0215152.

- ABRA, F. D., HUIJSER, M. P., MAGIOLI, M., BOVO, A. A. A., & de BARROS, K. M. P. M. 2021. An estimate of wild mammal roadkill in São Paulo state, Brazil. Heliyon, 7(1), e06015.

- ABREU, E. F., D. CASALI, R. COSTA-ARAÚJO, G. S. T. GARBINO, G. S. LIBARDI, D. LORETTO, A. C. LOSS, M. MARMONTEL, L. M. MORAS, M. C. NASCIMENTO, M. L. OLIVEIRA, S. E. PAVAN, & F. P. TIRELLI. (2021). Lista de Mamíferos do Brasil (2021-2) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5802047

» https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5802047 - ANTUNES, A. Z. & M. R. ESTON. 2009. Mamíferos (Chordata: Mammalia) florestais de médio e grande porte registrados em Barreiro Rico, Anhembi, Estado de São Paulo. Revista do Instituto Florestal 21:201–215.

- BAR-ON, Y. M., R. PHILLIPS & R. MILO. 2018. The biomass distribution on Earth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:6506–6511.

- BECA, G., M. H. VANCINE, C. S. CARVALHO, F. PEDROSA, R. S. C. ALVES, D. BUSCARIOL, C. A. PERES, M. C. RIBEIRO & M. GALETTI. 2017. High mammal species turnover in forest patches immersed in biofuel plantations. Biological Conservation 210:352–359.

- BEISIEGEL, B. M. & C. ADES. 2004. The bush dog Speothos venaticus (Lund, 1842) at Parque Estadual Carlos Botelho, Southeastern Brazil. Mammalia 68: 65–68.

- BEISIEGEL, B.M. & E. NAKANO-OLIVEIRA. 2020. Histórias de vida e guia fotográfico das onças-pintadas (Panthera onca, Carnivora: Felidae) do Contínuo de Paranapiacaba, São Paulo. Boletim da Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia 87:11–19.

- BELLO, C., L. CULOT, C. A. R. AGUDELO & M. GALETTI. 2021. Valuing the economic impacts of seed dispersal loss on voluntary carbon markets. Ecosystem Services 52:101362.

- BELLO, C., M. GALETTI, M. A. PIZO, L. F. MAGNAGO, M. F. ROCHA, R. A. LIMA, C. A. PERES, O. OVASKAINEN & P. JORDANO. 2015. Defaunation affects carbon storage in tropical forests. Sci Adv 1:e1501105.

- BERTHET, M., G. MESBAHI, G. DUVOT, K. ZUBERBÜHLER, C. CÄSAR & J. C. BICCA-MARQUES. 2021. Dramatic decline in a titi monkey population after the 2016–2018 sylvatic yellow fever outbreak in Brazil. American Journal of Primatology 83:e23335.

- BOVENDORP, R. S., R. A. MCCLEERY & M. GALETTI. 2017a. Optimising sampling methods for small mammal communities in Neotropical rainforests. Mammal Review 47:148–158.

- BOVENDORP, R. S., N. VILLAR, E. F. DE ABREU-JUNIOR, C. BELLO, A. L. REGOLIN, A. R. PERCEQUILLO & M. GALETTI. 2017b. Atlantic small-mammal: a dataset of communities of rodents and marsupials of the Atlantic forests of South America. Wiley Online Library.

- BREVIGLIERI, C. P. B., M. C. CASTRO, D. C. RIBEIRO, L. DE OLIVEIRA, J. H. P. DIAS & F. C. MONTEFELTRO. 2018. First confirmed records of the Pantanal Cat, Leopardus colocola braccatus (Cope, 1889), in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Check List 14:699.

- CARLSON, C.J., ALBERY, G.F., MEROW, C. et al. 2022. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w

» https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w - CARLUCCI, M. B., V. MARCILIO-SILVA & J. M. TOREZAN. 2021. The southern Atlantic Forest: use, degradation & perspectives for conservation. Pages 91–111. The Atlantic Forest. Springer.

- CARVALHO, C. S., M. E. DE OLIVEIRA, K. G. RODRIGUEZ-CASTRO, B. H. SARANHOLI & P. M. GALETTI JR. 2021. Efficiency of eDNA and iDNA in assessing vertebrate diversity and its abundance. Molecular Ecology Resources.

- COELHO, L., D. ROMERO, D. QUEIROLO & J. C. GUERRERO. 2018. Understanding factors affecting the distribution of the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) in South America: spatial dynamics and environmental drivers. Mammalian Biology 92:54–61.

- CRUZ, L. R., MUYLAERT, R. L., GALETTI, M., & PIRES, M. M. (2022). The geography of diet variation in Neotropical Carnivora. Mammal Review, 52(1): 112–128.

- CULOT, L., L. A. PEREIRA, I. AGOSTINI, M. A. B. DE ALMEIDA, R. S. C. ALVES, I. AXIMOFF, A. BAGER, M. C. BALDOVINO, T. R. BELLA, J. C. BICCA-MARQUES, C. BRAGA, C. R. BROCARDO, A. K. N. CAMPELO, G. R. CANALE, J. D. C. CARDOSO, E. CARRANO, D. C. CASANOVA, C. R. CASSANO, E. CASTRO, J. J. CHEREM, A. G. CHIARELLO, B. A. P. COSENZA, R. COSTA-ARAUJO, N. C. D. SILVA, M. S. DI BITETTI, A. S. FERREIRA, P. C. R. FERREIRA, M. S. FIALHO, L. F. FUZESSY, G. S. T. GARBINO, F. O. GARCIA, C. GATTO, C. C. GESTICH, P. R. GONCALVES, N. R. C. GONTIJO, M. E. GRAIPEL, C. E. GUIDORIZZI, R. O. ESPINDOLA HACK, G. P. HASS, R. R. HILARIO, A. HIRSCH, I. HOLZMANN, D. H. HOMEM, H. E. JUNIOR, G. S. JUNIOR, M. C. M. KIERULFF, C. KNOGGE, F. LIMA, E. F. DE LIMA, C. S. MARTINS, A. A. DE LIMA, A. MARTINS, W. P. MARTINS, F. R. DE MELO, R. MELZEW, J. M. D. MIRANDA, F. MIRANDA, A. M. MORAES, T. C. MOREIRA, M. S. DE CASTRO MORINI, M. B. NAGY-REIS, L. OKLANDER, L. DE CARVALHO OLIVEIRA, A. P. PAGLIA, A. PAGOTO, M. PASSAMANI, F. DE CAMARGO PASSOS, C. A. PERES, M. S. DE CAMPOS PERINE, M. P. PINTO, A. R. M. PONTES, M. PORT-CARVALHO, B. PRADO, A. L. REGOLIN, G. C. REZENDE, A. ROCHA, J. D. S. ROCHA, R. R. DE PAULA RODARTE, L. P. SALES, E. D. SANTOS, P. M. SANTOS, C. S. S. BERNARDO, R. SARTORELLO, L. SERRA, E. SETZ, E. S. A. S. DE ALMEIDA, L. H. D. SILVA, P. SILVA, M. SILVEIRA, R. L. SMITH, S. M. DE SOUZA, A. C. SRBEK-ARAUJO, L. C. TREVELIN, C. VALLADARES-PADUA, L. ZAGO, E. MARQUES, S. F. FERRARI, R. BELTRAO-MENDES, D. J. HENZ, F. E. DA VEIGA DA COSTA, I. K. RIBEIRO, L. L. T. QUINTILHAM, M. DUMS, P. M. LOMBARDI, R. T. R. BONIKOWSKI, S. G. AGE, J. P. SOUZA-ALVES, R. CHAGAS, R. CUNHA, M. M. VALENCA-MONTENEGRO, G. LUDWIG, L. JERUSALINSKY, G. BUSS, R. B. DE AZEVEDO, R. F. FILHO, F. BUFALO, L. MILHE, M. M. D. SANTOS, R. SEPULVIDA, D. D. S. FERRAZ, M. B. FARIA, M. C. RIBEIRO & M. GALETTI. 2019. ATLANTIC-PRIMATES: a dataset of communities and occurrences of primates in the Atlantic Forests of South America. Ecology 100:e02525.

- DE MELLO, A. B., J. MOLINA, M. KAJIN & M. C. DE O SANTOS. 2019. Abundance Estimates of Guiana Dolphins (Sotalia guianensis; Van Bénéden, 1864) Inhabiting an Estuarine System in Southeastern Brazil. Aquatic Mammals 45.

- DUARTE, J. M. B., U. PIOVEZAN, E. DOS SANTOS ZANETTI, H. G. DA CUNHA RAMOS, L. M. TIEPOLO, A. VOGLIOTI, M. L. DE OLIVEIRA, L. F. RODRIGUES & L. B. DE ALMEIDA. 2012. Avaliação do risco de extinção do cervo-do-Pantanal Blastocerus dichotomus Illiger, 1815, no Brasil. Biodiversidade Brasileira-BioBrasil:3–14.

- FEGIES, A. C., A. P. CARMIGNOTTO, M. F. PEREZ, M. D. GUILARDI & A. C. LESSINGER. 2021. Molecular Phylogeny of Cryptonanus (Didelphidae: Thylamyini): Evidence for a recent and complex diversification in South American open biomes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 162:107213.

- FERRAZ, K. M. P. M. D., M.-A. LECHEVALIER, H. T. Z. D. COUTO & L. M. VERDADE. 2003. Damage caused by capybaras in a corn field. Scientia Agricola 60:191–194.

- FERRAZ, K. M. P. M. D. B., S. MARCHINI, J. A. BOGONI, R. M. PAOLINO, M. LANDIS, R. FUSCO-COSTA, M. MAGIOLI, L. P. MUNHOES, B. H. SARANHOLI, Y. G. G. RIBEIRO, J. A. D. DOMINI, G. S. MAGEZI, J. C. Z. GEBIN, H. ERMENEGILDO, P. M. GALETTI JUNIOR, M. GALETTI, A. ZIMMERMANN & A. G. CHIARELLO. 2022. Best of both worlds: Combining ecological and social research to inform conservation decisions in a Neotropical biodiversity hotspot. Journal for Nature Conservation 66:126146.

- FIGUEIREDO, G. C., K. B. DO AMARAL & M. C. DE OLIVEIRA SANTOS. 2020. Cetaceans along the southeastern Brazilian coast: occurrence, distribution, and niche inference at local scale. PeerJ 8:e10000.

- FURTADO, L. O., G. R. FELICIO, P. R. LEMOS, A. V. CHRISTIANINI, M. MARTINS & A. P. CARMIGNOTTO. 2021. Winners and Losers: How Woody Encroachment Is Changing the Small Mammal Community Structure in a Neotropical Savanna. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9.

- GALETTI, M., C. R. BROCARDO, R. A. BEGOTTI, L. HORTENCI, F. ROCHA-MENDES, C. S. S. BERNARDO, R. S. BUENO, R. NOBRE, R. S. BOVENDORP, R. M. MARQUES, F. MEIRELLES, S. K. GOBBO, G. BECA, G. SCHMAEDECKE & T. SIQUEIRA. 2017. Defaunation and biomass collapse of mammals in the largest Atlantic forest remnant. Animal Conservation 20:270–281.

- GALETTI, M., H. C. GIACOMINI, R. S. BUENO, C. S. BERNARDO, R. M. MARQUES, R. S. BOVENDORP, C. E. STEFFLER, P. RUBIM, S. K. GOBBO & C. I. DONATTI. 2009a. Priority areas for the conservation of Atlantic forest large mammals. Biological Conservation 142:1229–1241.

- GALETTI, M., H. C. GIACOMINI, R. S. BUENO, C. S. S. BERNARDO, R. M. MARQUES, R. S. BOVENDORP, C. E. STEFFLER, P. RUBIM, S. K. GOBBO, C. I. DONATTI, R. A. BEGOTTI, F. MEIRELLES, R. D. A. NOBRE, A. G. CHIARELLO & C. A. PERES. 2009b. Priority areas for the conservation of Atlantic forest large mammals. Biological Conservation 142:1229–1241.

- GALETTI, M., F. GONÇALVES, N. VILLAR, V. B. ZIPPARRO, C. PAZ, C. MENDES, L. LAUTENSCHLAGER, Y. SOUZA, P. AKKAWI & F. PEDROSA. 2021. Causes and consequences of large-scale defaunation in the Atlantic forest. Pages 297–324. The Atlantic Forest. Springer.

- GALETTI, M., R. GUEVARA, C. L. NEVES, R. R. RODARTE, R. S. BOVENDORP, M. MOREIRA, J. B. HOPKINS & J. D. YEAKEL. 2015. Defaunation affect population and diet of rodents in Neotropical rainforests. Biological Conservation 190:2–7.

- GALETTI, M., F. PEDROSA, A. KEUROGHLIAN & I. SAZIMA. 2016. Liquid lunch–vampire bats feed on invasive feral pigs and other ungulates. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14:505–506.

- GARBINO, G. S. T. 2016. Research on bats (Chiroptera) from the state of São Paulo, southeastern Brazil: annotated species list and bibliographic review. Arquivos de Zoologia 47.

- GARCIA, F. D. O., L. CULOT, R. E. W. F. DE CARVALHO & V. J. ROCHA. 2022. Functionality of two canopy bridge designs: successful trials for the endangered black lion tamarin and other arboreal species. European Journal of Wildlife Research 68:1–14.

- GONCALVES, F., M. GALETTI & D. G. STREICKER. 2021. Management of vampire bats and rabies: a precaution for rewilding projects in the Neotropics. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 19:37–42.

- GONÇALVES, F., M. MAGIOLI, R. S. BOVENDORP, K. M. FERRAZ, L. BULASCOSCHI, M. Z. MOREIRA & M. GALETTI. 2020. Prey choice of introduced species by the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) on an Atlantic Forest land-bridge island. Acta Chiropterologica 22:167–174.

- HOLMES, E. C. 2022. COVID-19—lessons for zoonotic disease. American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- JERUSALINSKY, L., M. TALEBI & F. R. MELO. 2011. Plano de ação nacional para a conservação dos muriquis. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservaçao da Biodiversidade, Brasılia.