ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND:

Poor appetite is common through the aging process and increases the risk of weight loss, protein-energy malnutrition, immunossupression, sarcopenia and frailty. The Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ) has the aim to monitor appetite and identify older adults at risk of weight loss.

OBJECTIVE:

To describe the process of translation and cultural adaptation to Brazilian Portuguese of the SNAQ.

METHODS:

The translation and cultural adaptation was developed in five steps: translation (by three of the authors of the manuscript and assembled by consensus), backtranslation (by an English native speaker), semantic evaluation (by one verontologist and one nutritionist), comprehension of content (by nutrition specialists and by a group of older persons), pre-test and the SNAQ final version development.

RESULTS:

The SNAQ Portuguese version maintained the original version meaning and referral. To achieve this feature, the process required some modifications to improve the understanding of older persons, such as inclusion of other options to the answers of some questions, rewritten of one question and inclusion of a meal definition.

CONCLUSION:

SNAQ questionnaire has been successfully translated and adapted to Portuguese. As our next step, we are validating this tool in different clinical settings in Brazil.

HEADINGS:

Validation study; Surveys and questionnaires; Weight loss; Appetite; Aging

RESUMO

CONTEXTO:

A perda de apetite é comum durante o envelhecimento e aumenta o risco de perda de peso, desnutrição energético-proteica, imunossupressão, sarcopenia e fragilidade. O Simplified Nutritional Appetie Questionnaire (SNAQ) tem como objetivo monitorar o apetite e identificar idosos sob risco de perda de peso.

OBJETIVO:

Descrever o processo de tradução e adaptação cultural para o português do Brasil o questionário SNAQ.

MÉTODOS:

A tradução e adaptação cultural foram realizadas em etapas: tradução (por três autores do manuscrito e grupo para consenso), retrotradução para versão original (por inglês nativo), avaliação semântica (gerontólogo e nutricionista), compreensão de conteúdo (por nutricionistas especialistas e por um grupo de idosos), pré teste e desenvolvimento da versão final.

RESULTADOS:

A versão em português do SNAQ manteve o significado da versão original. Para alcançar este resultado foram necessárias algumas modificações durante o processo para aperfeiçoar a compreensão dos idosos, como a inclusão de outras opções para respostas de algumas questões, revisão de escrita de uma das questões e inclusão de uma definição para o que é refeição.

CONCLUSÃO:

A tradução e adaptação cultural do questionário SNAQ foram bem sucedidas. A próxima etapa será a validação desta ferramenta em diferentes contextos clínicos no Brasil.

DESCRITORES:

Estudo de validação; Inquéritos e questionários; Perda de peso; Apetite; Envelhecimento

INTRODUCTION

The aging process is commonly accompanied by poor appetite and/or decreased food intake. This condition, named anorexia of aging (AA), may result from psychological, sociological and physiological factors. AA is mostly associated with unfavorable prognosis11. Morley JE, Silver AJ. Anorexia in the elderly. Neurobiol Aging. 1988;9:9-16.

2. Wilson MM, Thomas DR, Rubenstein LZ, Chibnall JT, Anderson S, Baxi A, et al. Appetite assessment: simple appetite questionnaire predicts weight loss in community-dwelling adults and nursing home residents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1074-81.-33. Wysokinski A, Sobow T, Kloszewska I, Kostka T. Mechanisms of the anorexia of aging-a review. Age (Dordr). 2015;37:9821.. Loss of appetite and reduction of food intake lead to weight loss, increased risk of protein-energy malnutrition, immunosuppression, sarcopenia and frailty22. Wilson MM, Thomas DR, Rubenstein LZ, Chibnall JT, Anderson S, Baxi A, et al. Appetite assessment: simple appetite questionnaire predicts weight loss in community-dwelling adults and nursing home residents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1074-81.. The prevalence of AA is reported to be around 25% in community-dwelling older adults and 62% in hospital inpatients. Nursing home settings present the highest prevalence of 85%22. Wilson MM, Thomas DR, Rubenstein LZ, Chibnall JT, Anderson S, Baxi A, et al. Appetite assessment: simple appetite questionnaire predicts weight loss in community-dwelling adults and nursing home residents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1074-81.,44. Cox NJ, Ibrahim K, Sayer AA, Robinson SM, Roberts HC. Assessment and Treatment of the Anorexia of Aging: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2019;11:144..

Most of undernutrition screening tools evaluate loss of appetite as a component of multiple nutritional domains instead of an individual construct. The importance of evaluating specifically loss of appetite is to enable interventions, such as meal adjustments and/or supplementation, before the onset of weight loss and/or risk of malnutrition. The Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ) was developed as a smaller version of the Council of Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire (CNAQ), with the aim to monitor appetite and identify persons at risk for weight loss. The SNAQ is a 4-question screening tool validated in community-dwelling and institutionalized older adults, as well as among younger adults. The questions comprehend information on self-perception of appetite, satiety after meals, food taste and number of meals consumed daily. A score lower than 14 points identify persons at risk of losing significant weight (≥5% of body weight) in the next six months22. Wilson MM, Thomas DR, Rubenstein LZ, Chibnall JT, Anderson S, Baxi A, et al. Appetite assessment: simple appetite questionnaire predicts weight loss in community-dwelling adults and nursing home residents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1074-81..

Considering the lack of standardized, translated and culturally adapted tools to assess appetite in Brazil22. Wilson MM, Thomas DR, Rubenstein LZ, Chibnall JT, Anderson S, Baxi A, et al. Appetite assessment: simple appetite questionnaire predicts weight loss in community-dwelling adults and nursing home residents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1074-81.,44. Cox NJ, Ibrahim K, Sayer AA, Robinson SM, Roberts HC. Assessment and Treatment of the Anorexia of Aging: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2019;11:144.,55. Roberts HC, Lim SER, Cox NJ, Ibrahim K. The Challenge of Managing Undernutrition in Older People with Frailty. Nutrients. 2019;11:808., the aim of this study was to perform the translation and cultural adaptation of the SNAQ to Brazilian Portuguese.

METHODS

The procedures adopted in the present work were based on the “Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures”66. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186-91., together with other published translations of questionnaires to Brazilian Portuguese77. Roedinger MA, Marucci MFN, Latorre MRDO, Hearst N, Oliveira C, Duarte YAO, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation to the Portuguese language of the Determine Your Nutritional Health® screening method for the elderly in assisted living accommodation. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2017;22:509-18.

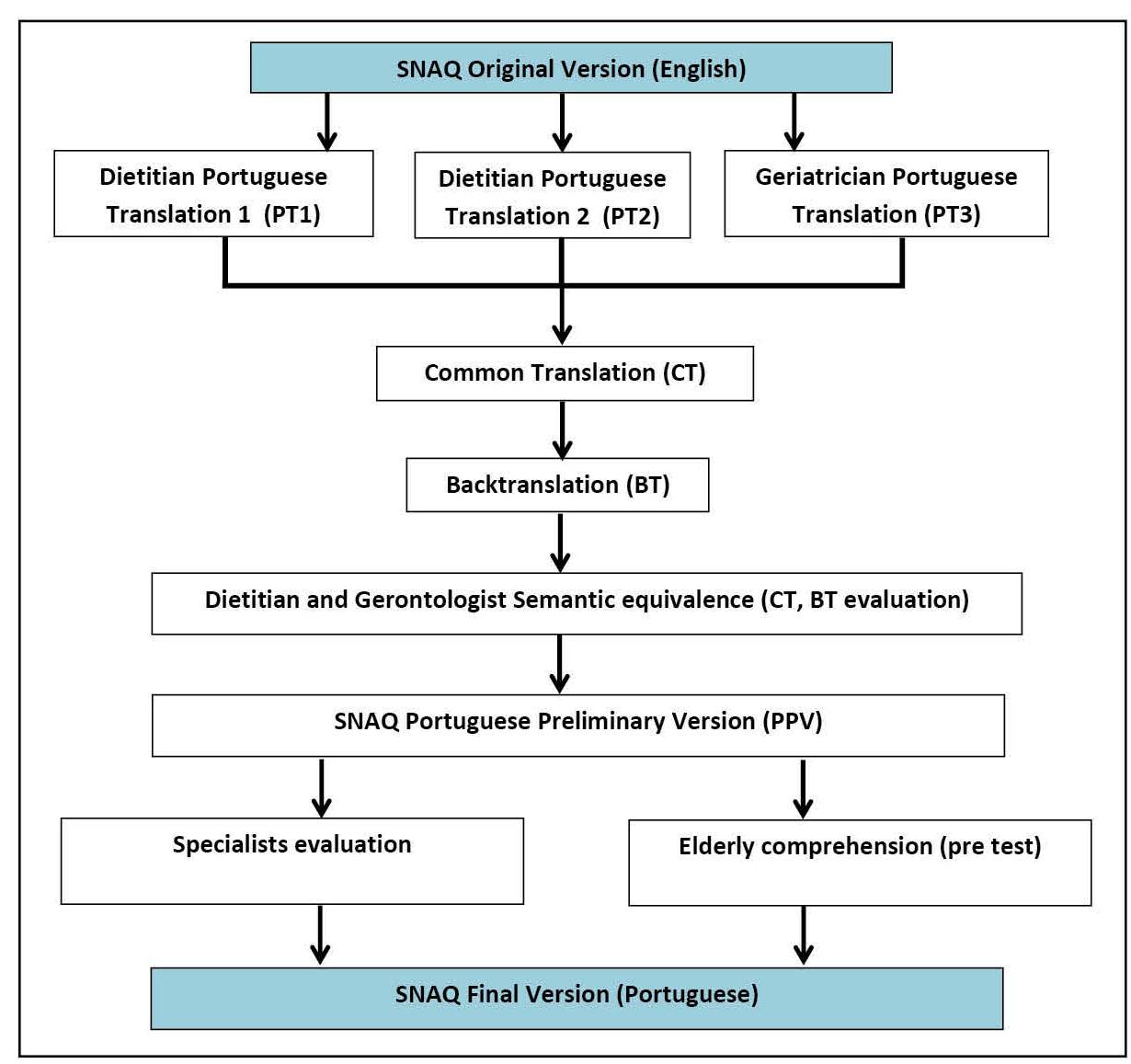

8. Conti MA, Scagliusi F, Queiroz GK, Hearst N, Cordas TA. Cross-cultural adaptation: translation and Portuguese language content validation of the Tripartite Influence Scale for body dissatisfaction. Cad Saude Publica. 2010;26:503-13.-99. Silveira MB, Saldanha RP, Leite JCC, Silva TOFD, Silva T, Filippin LI. Construction and validation of content of one instrument to assess falls in the elderly. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2018;16(2):eAO4154.. To achieve our aims, we divided the processes in five steps, as described below and outlined at Figure 1.

Step 1. Translation and back translation procedures

The original English version (OV) of the SNAQ was simultaneously translated by three authors of this manuscript, being two dietitians [PT1 (SMLR) and PT2 (MSZ)] and one geriatrician (PT3, IA), all of them are Brazilian Portuguese native speakers. A common translation (CT) was obtained after a consensus meeting between the three professionals. The CT was afterwards back translated (BT) by an English native speaker.

Step 2. Semantic evaluation

The CT and BT were submitted to a semantic evaluation by one gerontologist and one dietitian; those professionals did not take part on the first step of the project. They made suggestions related to some words or terms they considered more familiar to older adults. From these suggestions, we constructed the SNAQ Portuguese Preliminary version (PPV), which was simultaneously submitted to the Steps 3 and 4.

Step 3. Comprehension of content

The OV and the PPV were sent to 25 Brazilian dietitians who were specialists working with older adults in different settings (primary care, specialized ambulatory clinics, hospitals and nursing homes). The contact and submission of the material for analysis were made using the e-mail messages and Google Forms resources. The dietitians were instructed to carefully read both versions and answer numeric scales for each of the SNAQ questions, as following: (-1) non-equivalent, (0) undecided and (+1) equivalent. If considered necessary, the professionals could suggest changes on the PPV. The comprehension level was evaluated through a scale of 0 to 5 (0 for “not understand at all” and 5 for “perfectly understand with no doubts”) for each question. Sixteen dietitians returned the questionnaire to the authors.

Step 4. Pre-test of PPV

The pre-test of SNAQ was performed with a group of older adults who attend to an Open University in São Paulo, Brazil. This older adults signed a term of agreement before participation. The researchers evaluated the older adults’ comprehension according to the answers and doubts demonstrated as they answered the SNAQ. Older adults’ comprehension of each question was punctuated in the same way as in the Step 3 (a score from 0 to 5, where 0 means “not understand at all” and 5 means “perfectly understand with no doubts”).

Step 5. Validity of content and SNAQ final version

The validity of content was calculated according to the percentage of equivalent answers for each question. The mean and SD values for the oral comprehension (both specialists and older adults) were calculated with SPSS software version 23.

After the analysis of the comprehension and the content validity, the researches included observations and changed some terms to improve the SNAQ comprehension and to obtain the final version of the tool. The decision about the best terms to be used in the final version was made in a consensus meeting between two of the researchers (MSZ and SMLR). Most of the choices were based on the majority of the responders (both specialists and older adults). However, specific decisions were made with the help of electronic communications with one of the authors of the OV of the SNAQ (JEM).

Ethical standards

This study was derived from a broader research study and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the resolution 466/12 from CNS and approved by the Faculty of Medicine of Jundiaí Ethics Committee under the CAAE number: 12535218.5.3001.5412.

RESULTS

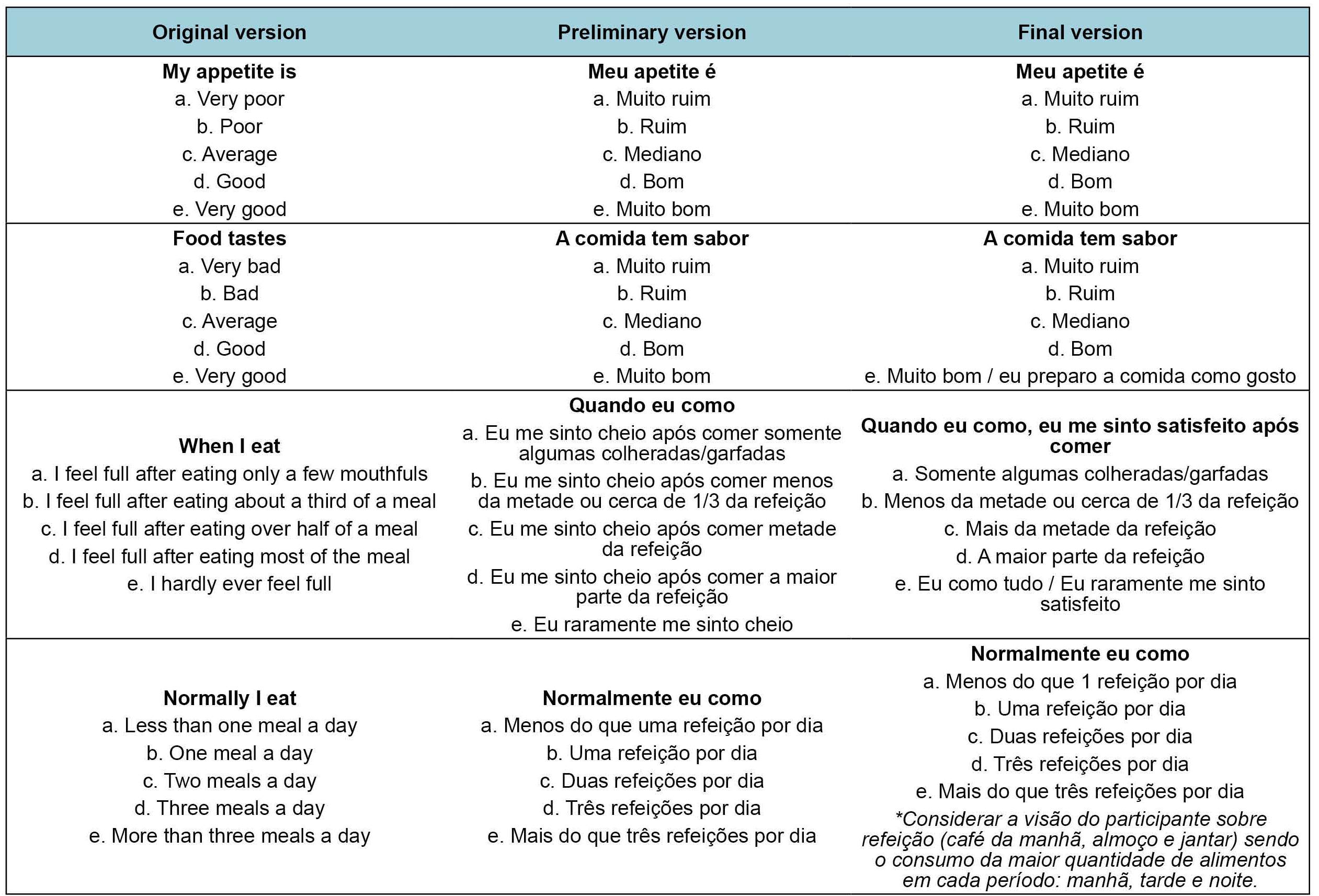

Figure 2 depicts the specialists’ suggestions and the final decisions about each question, and Table 1 shows the level of comprehension of the Brazilian Portuguese version of SNAQ. The content validity was above 80% for all the questions. The higher percentage was for question 1 (93.8%) and the lowest for question 3 (81.3%). The oral comprehension mean values were very similar for both specialists and older adults. Question 1 had the best oral comprehension value.

Translation and suggestions on the translation and cultural adaptation of the SNAQ questionnaire.

The terms “very poor”, “poor” and “average” (answers of the questions 1 and 2) were translated to “muito ruim”, “ruim” and “mediano”. Although two specialists suggested modifications to “sem apetite” and “regular”, the PPV terms were maintained, based on the majority’s acceptance of the PPV. However, not all the decisions were made based on the majority. Specifically, the term “feel full” was initially translated to “cheio”, but it was changed to “satisfeito” at the final version, because it implies the concept of “eat enough food”, according to the electronic communication with the author of the OV. In addition, the researchers also proposed to maintain the term “refeição” instead of “prato” (a specialist’s suggestion) on the last question of the SNAQ. However, to avoid misunderstandings, we decided to include a small note regarding the meaning of the word “meal”, as following: “Consider participant definition of meal (breakfast, lunch and dinner) being the largest eating occasion in each period: morning, afternoon and night1010. St-Onge MP, Ard J, Baskin ML, Chiuve SE, Johnson HM, Kris-Etherton P, et al. Meal Timing and Frequency: Implications for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e96-e121..

The SNAQ test was conducted with 20 older adults, mean age 69.1 (DP 6.8), from which 75% were female. During the SNAQ pre-test the researches noticed the older adults presented difficulties in answering about food taste (question 2), especially when they use to prepare their own meal (because they always cook what and how they like). As such, on the answer “e” (food tastes very good) it was added the option “I prepare food as I like”.

Question 3 had the lowest mean value on older adults’ comprehension because they had difficulty to choose between the long answers; in addition, they had doubts to answer in the situations in which they “usually eat everything”. The necessary changes in this case were to increase the question and reduce the answers, as following: “when I eat, I feel full after eating”: (a) only a few mouthfuls; (b) about a third of a meal; (c) over half of a meal; (d) most of the meal; (e) I hardly ever feel full; I eat everything”.

Figure 3 summarizes the description of the OV, PPV and Portuguese final version of SNAQ.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we performed the SNAQ translation, back translation and adaptation to Brazilian Portuguese. Several studies have emphasized the necessity to translate and culturally adapt different tools in order to guarantee that the data obtained express the originally intended information66. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186-91.

7. Roedinger MA, Marucci MFN, Latorre MRDO, Hearst N, Oliveira C, Duarte YAO, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation to the Portuguese language of the Determine Your Nutritional Health® screening method for the elderly in assisted living accommodation. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2017;22:509-18.-88. Conti MA, Scagliusi F, Queiroz GK, Hearst N, Cordas TA. Cross-cultural adaptation: translation and Portuguese language content validation of the Tripartite Influence Scale for body dissatisfaction. Cad Saude Publica. 2010;26:503-13.. The adaptation process requires that the translation method assures the original meaning and, simultaneously, enables comprehension according to the other culture66. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186-91.. We described here the procedures used on the SNAQ translation and adaptation do Portuguese which included three translations, back translation, semantic equivalence, content validity and comprehension by specialists and pre-test with older adults. In addition, we solved some issues with one of the authors of the questionnaire OV.

Considering the possibility of using the questionnaire in different health care settings, the specialists from those workplaces were invited for the content and comprehension analysis. SNAQ was originally validated to community-dwelling and institutionalized older adults, as well as to young adults. In our study, we had to make some changes, such as adding other answer options to some questions, rewriting question 3, and including a meal definition to improve understanding.

Because of its easy clinical use, the SNAQ questionnaire has also been translated and validated in different countries such as Japan, Australia and Malaysia1111. Tokudome Y, Okumura K, Kumagai Y, Hirano H, Kim H, Morishita S, et al. Development of the Japanese version of the Council on Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire and its simplified versions, and evaluation of their reliability, validity, and reproducibility. J Epidemiol. 2017;27:524-30.

12. Nakatsu N, Sawa R, Misu S, Ueda Y, Ono R, Yaxley A, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the simplified nutritional appetite questionnaire in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:1264-9.

13. Yaxley A, Crotty M, Miller M. Identifying Malnutrition in an Elderly Ambulatory Rehabilitation Population: Agreement between Mini Nutritional Assessment and Validated Screening Tools. Healthcare. 2015;3:822-9.-1414. Hanisah R, Suzana S, Lee FS. Validation of screening tools to assess appetite among geriatric patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:660-5.. In Brazil, it was previously translated and culturally adapted to a very specific population (older adults with cardiac diseases) from a specific setting in the South area of the country1515. Sties SW, Gonzáles AIs, Viana MdS, Brandt R, Bertin RL, Goldfeder R, et al. Questionário nutricional simplificado de apetite (QNSA) para uso em programas de Reabilitação cardiopulmonar e metabólica. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2012;18:313-7.; we understand that our present study added important informations to the previous one, since we adapted the tool to community-dwelling older adults and obtained the opinion of professionals from different health care setting.

CONCLUSION

The SNAQ questionnaire has been successfully translated and adapted to Portuguese. As continuation of our findings, we are currently validating the tool, investigating the sensibility and specificity in identifying the risk of weight loss in older adults from different settings and in adults with chronic conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank to Henrique Salmazo and Lilian Barbosa Ramos for the initial suggestions, and to all the dietitians who agreed to give their opinion on the comprehension of the SNAQ Portuguese version. We are also grateful to João Valentini Neto for the help in collecting the data.

REFERENCES

-

1Morley JE, Silver AJ. Anorexia in the elderly. Neurobiol Aging. 1988;9:9-16.

-

2Wilson MM, Thomas DR, Rubenstein LZ, Chibnall JT, Anderson S, Baxi A, et al. Appetite assessment: simple appetite questionnaire predicts weight loss in community-dwelling adults and nursing home residents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1074-81.

-

3Wysokinski A, Sobow T, Kloszewska I, Kostka T. Mechanisms of the anorexia of aging-a review. Age (Dordr). 2015;37:9821.

-

4Cox NJ, Ibrahim K, Sayer AA, Robinson SM, Roberts HC. Assessment and Treatment of the Anorexia of Aging: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2019;11:144.

-

5Roberts HC, Lim SER, Cox NJ, Ibrahim K. The Challenge of Managing Undernutrition in Older People with Frailty. Nutrients. 2019;11:808.

-

6Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186-91.

-

7Roedinger MA, Marucci MFN, Latorre MRDO, Hearst N, Oliveira C, Duarte YAO, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation to the Portuguese language of the Determine Your Nutritional Health® screening method for the elderly in assisted living accommodation. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2017;22:509-18.

-

8Conti MA, Scagliusi F, Queiroz GK, Hearst N, Cordas TA. Cross-cultural adaptation: translation and Portuguese language content validation of the Tripartite Influence Scale for body dissatisfaction. Cad Saude Publica. 2010;26:503-13.

-

9Silveira MB, Saldanha RP, Leite JCC, Silva TOFD, Silva T, Filippin LI. Construction and validation of content of one instrument to assess falls in the elderly. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2018;16(2):eAO4154.

-

10St-Onge MP, Ard J, Baskin ML, Chiuve SE, Johnson HM, Kris-Etherton P, et al. Meal Timing and Frequency: Implications for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e96-e121.

-

11Tokudome Y, Okumura K, Kumagai Y, Hirano H, Kim H, Morishita S, et al. Development of the Japanese version of the Council on Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire and its simplified versions, and evaluation of their reliability, validity, and reproducibility. J Epidemiol. 2017;27:524-30.

-

12Nakatsu N, Sawa R, Misu S, Ueda Y, Ono R, Yaxley A, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the simplified nutritional appetite questionnaire in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:1264-9.

-

13Yaxley A, Crotty M, Miller M. Identifying Malnutrition in an Elderly Ambulatory Rehabilitation Population: Agreement between Mini Nutritional Assessment and Validated Screening Tools. Healthcare. 2015;3:822-9.

-

14Hanisah R, Suzana S, Lee FS. Validation of screening tools to assess appetite among geriatric patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:660-5.

-

15Sties SW, Gonzáles AIs, Viana MdS, Brandt R, Bertin RL, Goldfeder R, et al. Questionário nutricional simplificado de apetite (QNSA) para uso em programas de Reabilitação cardiopulmonar e metabólica. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2012;18:313-7.

-

Disclosure of funding: no funding received

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

24 June 2020 -

Date of issue

Apr-Jun 2020

History

-

Received

29 Dec 2019 -

Accepted

20 Feb 2020