Abstracts

This study records, for the first time, the occurrence of all four male morphotypes in a population of Macrobrachium amazonicumfrom a continental environment, with an entirely freshwater life cycle. The specimens studied came from the Tietê River, state of São Paulo, Brazil, and were collected in a lotic environment downstream from Ibitinga Dam. This population was compared with other continental populations, including a population from the dam itself, collected in a previous study. Four samples of 30 minutes were taken monthly, using a trap, from January to April 2011. Each male specimen was measured with respect to seven body dimensions as follows: carapace length (CL), right cheliped length (RCL), dactyl length (DCL), propodus length (PPL), carpus length (CRL), merus length (ML) and ischium length (IL). The relative growth was analyzed based on the change in growth patterns of certain body parts in relation to the independent variable CL. The four male morphotypes proposed for the species were found using morphological and morphometric analyses. Different biological characteristics were found between the populations studied. The male population of the lake of Ibitinga and from Pantanal presented mean sizes and number of morphotypes lower than the population studied here. These differences seem to be closely related to ecological characteristics of the environments inhabited by these populations. Our results supported the hypothesis that coastal and continental populations of M. amazonicum belong to the same species.

freshwater prawn; allometry; Tietê River; Amazon River Prawn; morphotype characterization

Este estudo registra, pela primeira vez, a ocorrência dos quatro morfotipos de Macrobrachium amazonicum em uma população continental com ciclo de vida totalmente dulcícola. Os camarões são provenientes do Rio Tietê, estado de São Paulo, Brasil, e foram coletados em um ambiente lótico abaixo da Barragem de Ibitinga. Essa população foi comparada com outras populações provenientes de ambientes continentais, incluindo a de um estudo anterior na represa da barragem de Ibitinga. Quatro amostras de 30 minutos foram realizadas mensalmente, utilizando armadilhas, de janeiro a abril de 2011. Cada indivíduo macho foi mensurado em relação a sete dimensões corporais, sendo elas: comprimento da carapaça (CL), comprimento total do quelípodo direito (RCL), comprimento do dáctilo (DCL), comprimento do própodo (PPL), comprimento do carpo (CRL), comprimento do mero (ML) e comprimento do ísquio (IL). O crescimento relativo foi analisado de acordo com as mudanças nas taxas de crescimento de determinadas partes do corpo em relação à variável independente CL. Os quatro morfotipos descritos para a espécie foram encontrados, utilizando análises morfológicas e morfométricas. Diferentes características biológicas foram encontradas entre a população estudada e as demais, incluindo a proveniente do reservatório. A população de machos da represa de Ibitinga e do Pantanal apresentaram tamanhos médios e número de morfotipos inferiores aos da população estudada aqui. Essas diferenças parecem estar intimamente relacionadas às características ecológicas dos ambientes onde estas populações estão inseridas. A hipótese de que populações costeiras e continentais de M. amazonicumpertençam à mesma espécie é suportada por nossos resultados.

camarão de água doce; alometria; Rio Tietê; Camarão da Amazônia; caracterização morfotípica

Introduction

The Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum(Heller 1862) is endemic to South America, where the species extends from Venezuela to Argentina. It has a wide distribution in all of the main eastern South American river basins (Orinoco, Amazon, Araguaia-Tocantins and São Francisco) including isolated inland populations from the upper Paraná and Paraguay River systems (Holthuis, 1952HOLTHUIS, LB., 1952. A general revision of the Palaemonidae (Crustacea Decapoda Natantia) of the Americas. II. The subfamily Palaemoninae. Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press. 396 p. (Allan Hancock Foundations Publications. Occasional Paper, no. 12).; Rodriguez, 1982RODRIGUEZ, G., 1982. Fresh-water shrimps (Crustacea, Decapoda, Natantia) of the Orinoco basin and the Venezuelan Guayana. Journal of Crustacean Biology, vol. 2, no. 3, p. 378-391. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1548054.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1548054...

; Coelho and Ramos-Porto, 1984COELHO, PA. and RAMOS-PORTO, MR., 1984. Camarões de água doce do Brasil: distribuição geográfica. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 2, no. 6, p. 405-410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751984000200014.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751984...

; Lopez and Pereira, 1996LOPEZ, B. and PEREIRA, G., 1996. Inventario de los crustáceos decapodos de las zonas alta y media del delta del Rio Orinoco, Venezuela. Acta Biologica Venezuelica, vol. 16, no. 3, p. 45-64.; Pettovello, 1996PETTOVELLO, AD., 1996. First record of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in Argentina. Crustaceana, vol. 69, no. 1, p. 113-114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156854096X00141.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156854096X0014...

; Bialetzki et al., 1997BIALETZKI, A., NAKATANI, K., BAUMGARTNER, RG. and BOND-BUCKUP, G., 1997. Occurrence of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller) (Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in Leopoldo's inlet (Ressaco do Leopoldo), upper Paraná River, Porto Rico, Paraná, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 379-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751997000200011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751997...

; Magalhães, 2000MAGALHÃES, C., 2000. Diversity and abundance of decapod crustaceans in the Rio Negro Basin, Pantanal, MatoGrosso do Sul, Brazil. In WILLINK, P., CHERNOFF, B., ALONSO, LE., MONTAMBAULT, J. and LOURIVAL, R., (Eds.). A biological assessment of the aquatic ecosystems of the Pantanal, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Washington: Conservation International. p. 56-62.; 2001MAGALHÃES, C., 2001. Diversity, distribution, and habitats of the macro-invertebrate fauna of the Rio Paraguay and Rio Apa, Paraguay, with emphasis on decapod crustaceans 6872. In CHERNOFF, B., WILLINK, PW. and MONTAMBAULT, JR. (Eds.). A Biological Assessment of the Aquatic Ecosystems of the Rio Paraguay Basin, Alto Paraguay, Paraguay. Washington: Conservation International. (RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment, no. 19)., 2002MAGALHÃES, C., 2002. A rapid assessment of the decapod fauna in the Rio Tahuamanu and Rio Manuripi Basins, with new records of shrimps and crabs for Bolivia (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae, Sergestidae, Trichodactylidae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 19, no. 4, p. 1091-1103.; Melo, 2003MELO, GAS., 2003. Manual de Identificação dos Crustacea Decapoda de água doce do Brasil. São Paulo: Loyola. 429 p.; Valencia and Campos, 2007VALENCIA, DM. and CAMPOS, MR., 2007. Freshwater prawns of the genus Macrobrachium Bate, 1868 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae) of Colombia. Zootaxa, vol. 1456, p. 1-44.). According to Magalhães et al. (2005)MAGALHÃES, C., BUENO, SLS., BOND-BUCKUP, G., VALENTI, WC., SILVA, HLM., KIYOHARA, F., MOSSOLIN, EC. and ROCHA, S., 2005. Exotic species of freshwater decapod crustaceans in the state of São Paulo, Brazil: records and possible causes of their introduction. Biodiversity and Conservation, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 1929-1945. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-2123-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-212...

, this species is not native to the upper Paraná River basin but was either deliberately or accidentally introduced there. These inland populations do not depend on brackish water to complete the larval phase, in contrast of what occurs in coastal populations (Guest, 1979GUEST, WC., 1979. Laboratory life history of the palaemonid shrimp Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862) (Decapoda, Palaemonidae). Crustaceana, vol. 37, no. 2, p. 141-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156854079X00979.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156854079X0097...

).

Coastal and continental populations show intraspecific variations in their physiology, ecology, morphology (Maciel and Valenti, 2009MACIEL, CR. and VALENTI, WC., 2009. Biology, fisheries, and aquaculture of the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum: a review. Nauplius, vol. 17, no. 2, p. 61-79.; Hayd et al., 2008HAYD, L., ANGER, K. and VALENTI, WC., 2008. The moulting cycle of larval Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum reared in the laboratory. Nauplius, vol. 16, p. 55-63.; Anger and Hayd, 2009ANGER, K. and HAYD, L., 2009. From lecithotrophy to planktotrophy: ontogeny of larval feeding in the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquatic Biology, vol. 7, no. 1/2, p. 19-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.3354/ab00180.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3354/ab00180...

) and genetic structure (Vergamini et al., 2011VERGAMINI, FG., PILEGGI, LA. and MANTELATTO, FL., 2011. Genetic variability of the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda, Caridea, Palaemonidae). Contributions to Zoology, vol. 80, no. 1, p. 67-83.). Because of this, there is some discussion about the taxonomic status of coastal and continental populations (Moraes-Valenti and Valenti, 2010MORAES-VALENTI, P. and VALENTI, WC., 2010. Culture of the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum. In NEW, MB., VALENTI, WC., TIDWELL, JH., D'ABRAMO, LR. and KUTTY, MN. (Eds.). Freshwater prawns: biology and farming. Chichester: Wiley. p. 485-501.). Anger (2013)ANGER, K., 2013. Neotropical Macrobrachium (Caridea: Palaemonidae): On the biology, origin, and radiation of freshwater-invading shrimp. Journal of Crustacean Biology, vol. 33, no. 2, p. 151-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1937240X-00002124.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1937240X-00002...

and Hayd and Anger (2013)HAYD, L. and ANGER, K., 2013. Reproductive and morphometric traits of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda: Palaemonidae) from the Pantanal, Brazil, suggests initial speciation. Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 39-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.10881. PMid:23894962

http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.108...

suggested the hypothesis that shrimps from the Paraná-Paraguay basin, at least those in the Pantanal, may actually represent a separate, endemic species. According to these authors, differences in reproductive systems indicate that long vicariant separation has indeed allowed for diversification in different catchment areas, suggesting that M. amazonicum is actually a complex of closely related but separate species.

Macrobrachium amazonicum is the freshwater decapod of the greatest economic importance in the Eastern South American subcontinent (Maciel and Valenti, 2009MACIEL, CR. and VALENTI, WC., 2009. Biology, fisheries, and aquaculture of the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum: a review. Nauplius, vol. 17, no. 2, p. 61-79.). In Brazil, the species is intensively exploited by artisanal fisheries; it is also consumed as human food, most commonly in Northeastern Brazil and in the Amazon region, by all social classes (Moraes-Valenti and Valenti, 2010MORAES-VALENTI, P. and VALENTI, WC., 2010. Culture of the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum. In NEW, MB., VALENTI, WC., TIDWELL, JH., D'ABRAMO, LR. and KUTTY, MN. (Eds.). Freshwater prawns: biology and farming. Chichester: Wiley. p. 485-501.; Marques and Moraes-Valenti, 2012MARQUES, HLA. and MORAES-VALENTI, PMC., 2012. Current status and prospects of farming the giant river prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man 1879) and the Amazon river prawn (Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) in Brazil. Aquaculture and Research, vol. 43, no. 7, p. 984-992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2011.03032.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.20...

). In addition, the species has been used as bait in sport fishing and shows great potential for aquaculture (Kutty, 2005KUTTY, MN., 2005. Towards sustainable freshwater prawn aquaculture – lessons from shrimp farming, with special reference to India. Aquaculture and Research, vol. 36, no. 3, p. 255-263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01240.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.20...

; New, 2005NEW, MB., 2005. Freshwater prawn farming: global status, recent research and a glance at the future. Aquaculture and Research, vol. 36, no. 3, p. 210-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01237.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.20...

, Moraes-Valenti and Valenti, 2010MORAES-VALENTI, P. and VALENTI, WC., 2010. Culture of the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum. In NEW, MB., VALENTI, WC., TIDWELL, JH., D'ABRAMO, LR. and KUTTY, MN. (Eds.). Freshwater prawns: biology and farming. Chichester: Wiley. p. 485-501.).

Studies of natural populations of M. amazonicum have found wide variability in the size of the individuals, sometimes even in different localities of the same river (Odinetz-Collart, 1987ODINETZ-COLLART, O., 1987. La peche crevettiere de Macrobrachium amazonicum (Palaemonidae) dansleBas-Tocantins apreslafermeturedubarrage de Tucurui (Bresil). Revue d'Hydrobiologie Tropicale, vol. 20, no. 2, p. 131-144., 1993ODINETZ-COLLART, O., 1993. Ecologia e potencial pesqueiro do camarão-canela Macrobrachium amazonicum na Bacia Amazônica. In FERREIRA. EJG., SANTOS, GM., LEÃO, ELM. and OLIVEIRA, LA. (Eds.). bases científicas para estratégias de preservação e desenvolvimento da amazônia: fatos e perspectivas. Manaus: INPA. p. 147-166. vol. 2.; Odinetz-Collart and Moreira, 1993ODINETZ-COLLART, O. and MOREIRA, LC., 1993. Potencial pesqueiro de Macrobrachium amazonicum na Amazônia Central (Ilha do Careiro): variação da abundância e do comprimento. Amazoniana, vol. 12, no. 3-4, p. 399-413.). According to Odinetz-Collart (1988)ODINETZ-COLLART, O., 1988. Aspectos ecologicos do camarão Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862) no Baixo Tocantins (PA-Brasil). Memoria Sociedad de Ciencias Naturales La Salle, vol. 48, Supl., p. 341-353. and Odinetz-Collart and Moreira (1993)ODINETZ-COLLART, O. and MOREIRA, LC., 1993. Potencial pesqueiro de Macrobrachium amazonicum na Amazônia Central (Ilha do Careiro): variação da abundância e do comprimento. Amazoniana, vol. 12, no. 3-4, p. 399-413., prawns caught in flowing water of large rivers grew to larger sizes than did prawns collected in the lentic water of lakes and reservoirs that can reach sexual maturity at smaller sizes.

In this species, sexually mature males can have different morphotypes, which have different sizes, morphology, physiology and behavior. The presence of morphotypes in populations is an extremely important factor for reproduction because the dominant males are almost the only prawns that succeed in reproducing (Moraes-Riodades and Valenti, 2004MORAES-RIODADES, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2004. Morphotypes in male Amazon River Prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 236, no. 1-4, p. 297-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

). The four distinguishable male morphotypes identified by Moraes-Riodades & Valenti (2004)MORAES-RIODADES, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2004. Morphotypes in male Amazon River Prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 236, no. 1-4, p. 297-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

are as follows: Translucent Claw (TC), Cinnamon Claw (CC), Green Claw 1 (GC1), and Green Claw 2 (GC2). These morphotypes differ in cheliped morphology and in certain morphometric relationships. In TC prawns, the chelipeds are translucent, whereas in CC they are generally cinnamon-colored. Both types bear a few spines and some low prominences resembling very small tubercles. Types GC1 and GC2 have long, moss-green chelipeds adorned with long robust spines. In GC2, the cheliped length is always greater than the post-orbital length and the angles of the spines on the carpus and propodus are more open, ranging from 51° to 92°; whereas these angles vary from 34° to 65° in GC1.

Distinct morphotypes described for this species (Moraes-Riodades and Valenti, 2004MORAES-RIODADES, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2004. Morphotypes in male Amazon River Prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 236, no. 1-4, p. 297-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

) have been recorded only for coastal populations from culture ponds (Papa et al., 2004PAPA, LP., FRANCESCHINI-VICENTINI, IB., VICENTINI, CA. and PEZZATO, LE., 2004. Diferenciação morfotípica de machos do camarão de água doce Macrobrachium amazonicum a partir da análise do hepatopâncreas e do sistema reprodutor. ActaSientiarium. Animal Science, vol. 26, no. 4, p. 463-467.) and natural environments influenced by brackish water, e.g. in the Eastern Amazon region (Silva et al., 2009SILVA, GMF., FERREIRA, MAP., VON LEDEBUR, EICF. and ROCHA, RM., 2009. Gonadal structure analysis of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862) from a wild population: a new insight on the morphotype characterization. Aquaculture and Research, vol. 40, no. 7, p. 798-803. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2009.02165.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.20...

; Moraes-Valenti et al., 2010MORAES-VALENTI, PMC., MORAES, PA., PRETO, BL. and VALENTI, WC., 2010. Effect of density on population development in the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquatic Biology, vol. 9, no. 3, p. 291-301. http://dx.doi.org/10.3354/ab00261.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3354/ab00261...

) and in Northeastern Brazil (Santos et al., 2006SANTOS, JA., SAMPAIO, CMS. and SOARES-FILHO, AA., 2006. Male population structure of the Amazon River prawn (Macrobrachium amazonicum) in a natural environment. Nauplius, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 55-63.). In a previous study, Pantaleão et al. (2012)PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011....

investigating the occurrence of different morphotypes in a continental population from a hydroelectric reservoir in the Tietê River, collected 587 males, in a period of one year, and only found TC morphotype (the first ontogenetic stage).

This study recorded for the first time, the occurrence of all four male morphotypes of M. amazonicum, which were defined by Moraes-Riodades and Valenti (2004)MORAES-RIODADES, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2004. Morphotypes in male Amazon River Prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 236, no. 1-4, p. 297-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

, in a continental population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Additionally, here we compare the sizes and male morphotypes of M. amazonicumamong the population of the flowing waters downstream the Ibitinga Dam, in the Tietê River, state of São Paulo, Brazil, the population studied before by Pantaleão et al. (2012)PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011....

of the lentic waters upstream from the reservoir and a population of the same hydrographic basin at Pantanal region.

Material and Methods

2.1.Study location

The collections were conducted in the lower of the Ibitinga Reservoir on the Tietê River. The dam is located in the municipality of Cambaratiba (24° 44′ 29″ S; 49° 01′ 27″W), in the central-western region of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, in the basin of the Paraná River. The collection site was located downstream of the reservoir of Ibitinga Hydroelectric Power Plant, in a lotic environment with a sandy bottom and marginal vegetation consisting of grasses (Cynodondactylon (L.) Pers. and Brachiaria subquadripara (Trin.) Hitchc.) and aquatic macrophytes (Egeria densa Planch., Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms. and Typha angustifolia (L.)).

The collection site was in a stretch of the Tietê River with great sport fishing activity. There is strong human disturbance here, caused by an excessive external supply of nutrients, such as fish food (pellets), viscera of caught fish and corn, to attract fish for sport fishing. This oversupply of food also ends up attracting prawns, which are usually used as bait, especially to catch silver croaker Plagioscion squamosissimus (Heckel, 1840).

2.2.Sampling

Four samples were taken during the morning, in each month, from January through April 2011 (16 samples). To ensure non-selective sampling and capture specimens of all sizes, we used a trap similar to a “Matapi” (made of natural fiber), commonly used in the Amazon region in Brazil (see Odnetz-Collart, 1993), but made of plastic material. The trap was placed near the macrophytes at depths of 1-2 meters and remained at each site for 30 minutes. Afterwards, the trap was removed, and the captured material was screened. The bait used for this sample was crushed corn and viscera of fish, similar to that used by most sport fishermen.

Once captured, the prawns were immediately taken to the laboratory for analysis. The prawns were sexed and identified by the presence or absence of the appendix masculina on the second pair of pleopods (Valenti, 1998VALENTI, WC., 1998. Carcinicultura de água doce: tecnologia para produção de camarões. Brasília: IBAMA. 383 p.). Only males were used in the analysis.

2.3.Identification of morphotypes

All measurements were based in the method of Kuris et al. (1987)KURIS, AM., RA'ANAN, Z., SAGI, A. and COHEN, D., 1987. Morphotypic differentiation of male Malaysian giantprawns, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Journal of Crustacean Biology, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 219-237. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1548603.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1548603...

and Moraes-Riodades and Valenti (2004)MORAES-RIODADES, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2004. Morphotypes in male Amazon River Prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 236, no. 1-4, p. 297-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

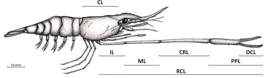

for morphotype characterization. The following dimensions were measured with a digital caliper (0.01mm) (Figure 1): carapace length (CL), right cheliped length (RCL), dactyl length (DCL), propodus length (PPL), carpus length (CRL), merus length (ML) and ischium length (IL).

Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862): dimensions used in the morphometric analyses. Carapace length(CL), right cheliped length (RCL), dactyl length (DCL), propodus length (PPL), carpus length (CRL), merus length (ML) and ischium length (IL).

A Principal Components Analysis (PCA) was performed on the (ln) data for the morphological variables of ten males of each CL class (5 mm classes) (Figure 2). This analysis was conducted as an exploratory tool to search for any evidence of groups' separation and reduce the number of variables. Consequently, we could determine which of these initial variables has more influence on the differentiation of possible morphological categories (morphotypes).

Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862): projection scores of the first and second principal components, generated with the principal components analyses performed on male's morphometric data.

In another step, a non-hierarchical analysis of K-means clustering was conducted, primarily to separate the juveniles from the adults and secondarily to separate the morphotypes. This method distributes the data into groups of numbers previously established by an iterative process that minimizes the variance within groups and maximizes the variance among them. The results of the K-means classification were refined by applying a discriminant analysis.

After the identification of the morphotypes by the K-means clustering analysis, a linear regression analysis was conducted using the data from the juveniles and from each morphotype. A covariance analysis (ANCOVA) was done to test the linear and angular coefficients among the juveniles and the sequential morphotypes found. This analysis showed whether the data for each morphological group were better adjusted to a single straight line or if the morphotypes should be represented by different linear equations.

After identification of the presence of morphotypes, chelipeds of ten animals per group were photographed with a Nikon D5000 digital camera (12.3 megapixels). The photographs were then used to measure the angles of the spines on the distal portion of the carpus and the proximal portion of the propodus using the Image J 1.44 software program. The mean angle and standard deviation were then calculated for each group.

3.Results

Carapace length ranged from 4.8 to 20.6 mm. Table 1 provides a detailed description of each group. Juvenile prawns had a carapace length (CL) of 4.80-8.80 mm. Right cheliped length (RCL) ranged from 9.90 to 15.70 mm. In general, chelipeds were translucent and did not have spines. TC prawns presented a CL ranging from 8.70 to 18.30 mm and RCL ranging from 14.80 to 47.60 mm. In general, chelipeds had few spines and segments were translucent. Prawns of the CC morphotype had a CL of 12.10-20.60 mm. RCL ranged from 28.50 to 79.10 mm, with about three times more spines than TC prawns. Brownish coloring was predominant in chelipeds. GC1 animals presented a CL ranging from 13.20 to 19.40 mm and RCL ranging from 37.20 to 75.20 mm. All joints presented more setae and spines than TC and CC, while fingers were distinctly velvety pubescent. In general chelipeds were greenish and terminal segments (carpus, propodus and dactyl) more intensely moss green coloured. Prawns of GC2 morphotype presented a CL ranging from 14.10 to 20.60 mm, and RCL ranged from 46.40 to 106.30. The pattern of color, spines and setae was similar to that of GC1. However, cheliped length was always greater in GC2.

The PCA indicated a possible separation of distinct morphological groups (Figure 2 and Table 2) for males of M. amazonicum. The principal component 1 and 2 (PC1 and PC2) explained most of the variation (98.65% and 0.75%, respectively). The propodus size (PPL) was the variable that had the highest contribution to PC1, indicating that this structure could be used to separate males in different morphotypes.

Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862): factor coordinates based on the correlations (Cor.) and contribution (Con.) of the morphometric variables, as resulted from the PCA.

The relationship that best demonstrated a clear difference among the groups studied was PPL vs. CL, with an estimated size at onset of morphological sexual maturity of 8.8 mm of CL. This relationship was utilized in the K-means classification analysis. The linear regression analysis for this relationship demonstrated a lower allometric coefficient (b) for the juveniles when compared to the four subsequent castes (Figure 3). Significant differences were found among all morphotypes, but CC vs. GC1 and GC1 vs. GC2 showed similar allometric coefficient rates (Figure 3 and Table 3).

Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862): separation of the male morphotypes obtained in the relationship PPL vs. CL by the K-means clustering analysis.

Four groups of males, differing in color,spination pattern and body relationships, were identified. Figure 4 shows a specimen from each group, demonstrating differences in the cheliped size and the spination pattern. The mean value of spine angles for the four groups is presented on Table 4. The TC group differed in size, whereas CC, GC1 and GC2 were of very similar size and larger than TC. The angles of spines on the carpus and propodus were more open in more developed castes, ranging from 8 to 20° in TC morphotype, 21 to 41° in CC, 35 to 54° in GC1 prawns and 37 to 64° in GC2 animals.

Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862): four male morphotypes captured in the population of Tietê River and spination pattern of the right carpus. TC = Translucent Claw, CC = Cinnamon Claw, CG1 = Green Claw 1, GC2 = Green Claw 2.

Discussion

Morphologic and morphometric analysis confirmed the division of male Macrobrachium amazonicum into distinct groups. Our results indicated that the natural male population of M. amazonicum from flowing waters downstream of the Ibitinga Reservoir on the Tietê River is composed of four groups of adult males differing in cheliped morphology, size and in morphometric relationships, as described for this species by Moraes-Riodades and Valenti (2004)MORAES-RIODADES, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2004. Morphotypes in male Amazon River Prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 236, no. 1-4, p. 297-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

, using males from culture ponds. Each group presents a specific growth pattern on body relationships, demonstrated by the differences in the allometric growth constant.

According to the allometric coefficients obtained in the morphometric analysis, morphotypes CC, GC1 and GC2 have very similar body size relationships between carapace and propodus (Figure 3and Table 3). Thus, the passage from one morphotype to another in a natural environment could occur through a single molt. Additionally, the spination pattern of the chelipeds among the four morphotypes of our specimens was quite different, similar to demonstrated by Moraes-Riodades and Valenti (2004)MORAES-RIODADES, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2004. Morphotypes in male Amazon River Prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 236, no. 1-4, p. 297-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

. According to these authors, changes in cheliped size, color and spination necessarily cause deep modifications to the intraspecific interactions and in the male's interaction with the environment. Each morphotype certainly has a different function in the population and in the environment in which it lives, conferred by the characteristics of its chelipeds.

Papa et al. (2004)PAPA, LP., FRANCESCHINI-VICENTINI, IB., VICENTINI, CA. and PEZZATO, LE., 2004. Diferenciação morfotípica de machos do camarão de água doce Macrobrachium amazonicum a partir da análise do hepatopâncreas e do sistema reprodutor. ActaSientiarium. Animal Science, vol. 26, no. 4, p. 463-467. and Silva et al. (2009)SILVA, GMF., FERREIRA, MAP., VON LEDEBUR, EICF. and ROCHA, RM., 2009. Gonadal structure analysis of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862) from a wild population: a new insight on the morphotype characterization. Aquaculture and Research, vol. 40, no. 7, p. 798-803. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2009.02165.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.20...

studied the morphology of the testes of the male morphotypes of M. amazonicum,identified by Moraes-Riodades and Valenti (2004)MORAES-RIODADES, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2004. Morphotypes in male Amazon River Prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 236, no. 1-4, p. 297-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

, demonstrating that GC1 and GC2 are very similar and thus, suggesting that they should be grouped together. Similarly, these two morphotypes presented similar body sizes in the present study, what was also demonstrated by Moraes-Riodades and Valenti (2004)MORAES-RIODADES, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2004. Morphotypes in male Amazon River Prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 236, no. 1-4, p. 297-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

. On the other hand, even if GC1 and GC2 have identical gonads and very similar body size, the differences in weight and size of chelipeds can be reflected in their different roles in the environment, which would characterize them as distinct castes. In this manner, further behavioral studies should be performed to understand the reproductive role of each morphotype, as suggested by Maciel and Valenti (2009)MACIEL, CR. and VALENTI, WC., 2009. Biology, fisheries, and aquaculture of the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum: a review. Nauplius, vol. 17, no. 2, p. 61-79..

Odinetz-Collart (1988)ODINETZ-COLLART, O., 1988. Aspectos ecologicos do camarão Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862) no Baixo Tocantins (PA-Brasil). Memoria Sociedad de Ciencias Naturales La Salle, vol. 48, Supl., p. 341-353., studying populations of M. amazonicum upstream and downstream of the Tucuruí hydroelectric power plant on the Tocantins River, noted that the two populations had different biological characteristics. The population from the lake had lower mean sizes, with a smaller size at sexual maturity. This size difference was attributed to differences in the quantity and quality of food, due to the flood cycle. These differences in features were also observed between the male population studied here and that of the lake of Ibitinga (Pantaleão et al., 2012PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011....

), which presented maximum values and size at onset of sexual maturity for males lower than the population of the flowing waters downstream of the dam (Table 5).

Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862): descriptive statistics for males collected at each local in the Tietê River, São Paulo. (CL); s.d. = standard deviation; Max S = maximum size; SOM = size at onset of the sexual maturity; M = number of morphotypes.

According to available literature, coastal prawn populations grow larger than continental populations (Moraes-Valenti and Valenti, 2010MORAES-VALENTI, P. and VALENTI, WC., 2010. Culture of the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum. In NEW, MB., VALENTI, WC., TIDWELL, JH., D'ABRAMO, LR. and KUTTY, MN. (Eds.). Freshwater prawns: biology and farming. Chichester: Wiley. p. 485-501.), as well as compared with individuals from lotic and lentic environments (Odinetz-Collart, 1988ODINETZ-COLLART, O., 1988. Aspectos ecologicos do camarão Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862) no Baixo Tocantins (PA-Brasil). Memoria Sociedad de Ciencias Naturales La Salle, vol. 48, Supl., p. 341-353.; Odinetz-Collart and Moreira, 1993ODINETZ-COLLART, O. and MOREIRA, LC., 1993. Potencial pesqueiro de Macrobrachium amazonicum na Amazônia Central (Ilha do Careiro): variação da abundância e do comprimento. Amazoniana, vol. 12, no. 3-4, p. 399-413.; Pantaleão et al., 2012PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011....

). In the present study this pattern was also observed. The largest carapace length of male specimens of M. amazonicum collected in a lotic environment by the present study (20.6 mm) was above that reported in a reservoir of the same river by Pantaleão et al. (2012)PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011....

(8.5 mm) and that reported to Hayd and Anger (2013)HAYD, L. and ANGER, K., 2013. Reproductive and morphometric traits of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda: Palaemonidae) from the Pantanal, Brazil, suggests initial speciation. Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 39-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.10881. PMid:23894962

http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.108...

for another continental population of the same hydrographic basin (Paraná-Paraguay) (11.1). However, when we compare our results with those obtained by Santos et al. (2006)SANTOS, JA., SAMPAIO, CMS. and SOARES-FILHO, AA., 2006. Male population structure of the Amazon River prawn (Macrobrachium amazonicum) in a natural environment. Nauplius, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 55-63. for a coastal population that also presents morphotypes, the mean carapace length of the largest specimens (41.75 ± 2.99) is nearly twice the observed for the continental population studied here. Nevertheless, these authors mentioned that GC2 morphotypes were not captured by them because of the trap used (casting net). So the difference in size of prawns could be greater.

Another difference among the population studied and other continental populations (Pantaleão et al., 2012PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011....

; Hayd and Anger, 2013HAYD, L. and ANGER, K., 2013. Reproductive and morphometric traits of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda: Palaemonidae) from the Pantanal, Brazil, suggests initial speciation. Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 39-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.10881. PMid:23894962

http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.108...

) may be seen in the minimum sexable size of males (appearance of appendix masculina). In the Tietê reservoir and Pantanal, smallest males could be observed with 4.0 and 2.5 mm of carapace length respectively, while in the present study this value was 4.8 mm. This also occurs with size of morphological sexual maturity, estimated with relative growth at 4.26 and 8.8 mm (CL) for the populations upstreams and downstreams of the dam in Tietê river, respectively. However, this estimative is not available in the works of Santos et al. (2006)SANTOS, JA., SAMPAIO, CMS. and SOARES-FILHO, AA., 2006. Male population structure of the Amazon River prawn (Macrobrachium amazonicum) in a natural environment. Nauplius, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 55-63. and Hayd and Anger (2013)HAYD, L. and ANGER, K., 2013. Reproductive and morphometric traits of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda: Palaemonidae) from the Pantanal, Brazil, suggests initial speciation. Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 39-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.10881. PMid:23894962

http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.108...

.

According to Pantaleão et al. (2012)PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011....

, it is believed that the population of the reservoir have “pure search” or promiscuous mating systems, with little pre-copulatory interactions or intra-male agonistic behavior. As a consequence, males do not need to grow to a large size nor to develop large cheliped weapons that would aid them in battling other males for females. They remain small, cryptic, and highly mobile (Bauer, 2004BAUER, RT., 2004. Remarkable shrimps: adaptations and natural history of the Carideans. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. 282 p.).

This type of mating behavior was also observed in the Pantanal shrimps by Hayd and Anger (2013)HAYD, L. and ANGER, K., 2013. Reproductive and morphometric traits of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda: Palaemonidae) from the Pantanal, Brazil, suggests initial speciation. Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 39-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.10881. PMid:23894962

http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.108...

. However it is clearly not characteristic of the studied population here, which presents (large) male morphotypes with strongly developed chelipeds. The presence of these morphotypes in a species suggests that they guard and defend females during mating interactions (Thiel et al., 2010THIEL, M., SOLOMON, TCC. and DUMONT, CP., 2010. Male Morphotypes and Mating Behavior of the Dancing Shrimp Rhynchocinetesbrucei (Decapoda: Caridea). Journal of Crustacean Biology, vol. 30, no. 4, p. 580-588. http://dx.doi.org/10.1651/09-3272.1.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1651/09-3272.1...

). Similarly to observed in the present comparison, Mashiko (1983)MASHIKO, K., 1983. Comparison of growth pattern until sexual maturity between the estuarine and upper freshwater populations of the prawn Macrobrachium nipponense (de Haan) within a river. Japanese Journal of Ecology, vol. 33, p. 207-212. suggested the presence of separate populations of Macrobrachium nipponense (De Haan 1849) within the same river. It was reported that freshwater individuals differ from estuarine individuals in a few essential reproductive characteristics.

In relation to the taxonomic status of coastal and continental populations, Anger (2013)ANGER, K., 2013. Neotropical Macrobrachium (Caridea: Palaemonidae): On the biology, origin, and radiation of freshwater-invading shrimp. Journal of Crustacean Biology, vol. 33, no. 2, p. 151-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1937240X-00002124.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1937240X-00002...

explains that the La Plata drainage system (Paraguay and Paraná rivers and adjacent inland waters of the Pantanal plains), has been hydrologically separated from the Amazon and Orinoco plains at least since the Pliocene (about 4 Ma). According to this author, in these inland populations, female downstream migrations or a passive larval export to estuarine waters must be considered as biologically impossible, which raises the question if coastal, estuarine, and hololimnetic inland populations assigned to M. amazonicum can really belong to the same species. In contrast, Vergamini et al. (2011)VERGAMINI, FG., PILEGGI, LA. and MANTELATTO, FL., 2011. Genetic variability of the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda, Caridea, Palaemonidae). Contributions to Zoology, vol. 80, no. 1, p. 67-83. and Robe et al. (2012)ROBE, LJ., MACHADO, S. and BARTHOLOMEI-SANTOS, ML., 2012. The DNA barcoding and the caveats with respect to its application to some species of Palaemonidae (Crustacea, Decapoda). Zoological Science, vol. 29, no. 10, p. 714-724. http://dx.doi.org/10.2108/zsj.29.714. PMid:23030345

http://dx.doi.org/10.2108/zsj.29.714...

, using molecular data, showed that both coastal and continental populations form a single monophyletic clade, and that the rates of genetic divergence are at the intraspecific level.

Hayd and Anger (2013)HAYD, L. and ANGER, K., 2013. Reproductive and morphometric traits of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda: Palaemonidae) from the Pantanal, Brazil, suggests initial speciation. Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 39-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.10881. PMid:23894962

http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.108...

mentioned the lack of morphotypes in the Paraná-Paraguay Basin as a consistent difference in population structure and reproductive traits. Morphotypes in a continental population, including the Paraná-Paraguay Basin had not yet been demonstrated (Moraes-Valenti and Valenti, 2010MORAES-VALENTI, P. and VALENTI, WC., 2010. Culture of the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum. In NEW, MB., VALENTI, WC., TIDWELL, JH., D'ABRAMO, LR. and KUTTY, MN. (Eds.). Freshwater prawns: biology and farming. Chichester: Wiley. p. 485-501.); therefore, our findings do not reinforce the hypothesis of Hayd and Anger (2013)HAYD, L. and ANGER, K., 2013. Reproductive and morphometric traits of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda: Palaemonidae) from the Pantanal, Brazil, suggests initial speciation. Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 39-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.10881. PMid:23894962

http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.108...

. A possible explanation for the differences noted is the fact that M. amazonicum is not native of Tietê River (Magalhães et al., 2005MAGALHÃES, C., BUENO, SLS., BOND-BUCKUP, G., VALENTI, WC., SILVA, HLM., KIYOHARA, F., MOSSOLIN, EC. and ROCHA, S., 2005. Exotic species of freshwater decapod crustaceans in the state of São Paulo, Brazil: records and possible causes of their introduction. Biodiversity and Conservation, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 1929-1945. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-2123-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-212...

). The species may have been introduced into the state of São Paulo between 1966 and 1973 together with M. jelskii (Miers, 1877) in the CESP (Companhia Energética de São Paulo) fish-farming stations, as part of the process of transplanting of the Sciaenidae fish P. squamosissimus from reservoirs in northeastern Brazil (Torloni et al., 1993TORLONI, CEC., SANTOS, JJ., CARVALHO, AAJR. and CORRÊA, ARA., 1993. A pescada-do-Piauí Plagioscionsquamosissimus (Heckel, 1840) (Osteichthyes, Perciformes) nos reservatórios da Companhia Energética de São Paulo – CESP. São Paulo: CESP. p. 1-23. Série Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento, vol. 84.). However, apart of where the shrimps have been brought, in Tietê River they complete their entirely life cycle in freshwater, and there are clear reproductive differences between the population from a reservoir (Pantaleão et al., 2012PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011....

) and the population downstreams, showing that regardless of the population of the Pantanal treat yourself a distinct species, M. amazonicum is still highly plastic.

Therefore, our hypothesis is that the high degree of plasticity in morphological characters among populations throughout the geographical distribution of M. amazonicum in Brazil is more related to environmental changes, mainly the availability of nutrients, which could explain the absence of morphotypes observed previously in the same river (Pantaleão et al., 2012PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011....

), in a place with different environmental characteristics.

The characteristics of the collection site, because of the intense food supply (see M & M for details), are very similar to the situation created in an environment where cage farming tanks are deployed to fatten fish up. The input of nutrients into the local environment, as occurs in the cage farming stretch, enriches the trophic web, influencing the secondary production more markedly than the primary production. Although this might seem like a paradox, it is correlated to the fact that the wild animals directly consume spilled food and feces from the fish farm, which interferes with the dynamics of various ecological processes and nutrient contributions (Håkanson, 2005HÅKANSON, L., 2005. Changes to lake ecosystem structure resulting from fish cage farm emissions. Lakes and Reservoirs: Research and Management, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 71-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1770.2005.00253.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1770.20...

). According to Ramos et al. (2008)RAMOS, IP., VIDOTTO-MAGNONI, AP. and CARVALHO, ED., 2008. Influence of cage fish farming on the diet of dominant fish species of a Brazilian reservoir (Tietê River, High Paraná River basin). Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia, vol. 20, no. 3, p. 245-252., the standard length values of fish species are statistically higher for specimens sampled around the cage farming systems in the Tietê River, which is most likely also occurring with M. amazonicum.

Therefore, even though different male morphotypes are a characteristic of M. amazonicum, the development, or lack of development, of the complete male population structure may be site-dependent (Maciel and Valenti, 2009MACIEL, CR. and VALENTI, WC., 2009. Biology, fisheries, and aquaculture of the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum: a review. Nauplius, vol. 17, no. 2, p. 61-79.), reinforcing the hypothesis that this development is modulated by environmental factors (Preto et al., 2010PRETO, BL., KIMPARA, JM., MORAES-VALENTI, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2010. Population structure of pond-raised Macrobrachium amazonicum with different stocking and harvesting strategies. Aquaculture, vol. 307, no. 3-4, p. 206-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2010.07.023.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

; Pantaleão et al., 2012PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011....

). In this context, further studies should be conducted to better understand how the environmental factors influence the complete male population structure development of M. amazonicum, maybe exposing juveniles from different water systems to different factors in a well-planned factorial experiment could corroborate this hypothesis.

Knowledge of the life history of the different populations of the species remains fragmentary (Anger et al., 2009ANGER, K., HAYD, L., KNOTT, U. and NETTELMANN, U., 2009. Patterns of larval growth and chemical composition in the Amazon River prawn, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 287, no. 3–4, p. 341-348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.10.042.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture....

) and focused on populations of environments influenced by brackish water. It is therefore necessary to perform complementary studies focusing on other types of environments, which will certainly improve the understanding of the wide morphological and reproductive plasticity existing among populations of continental and coastal waters.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank FAPESP for providing financial support for laboratory activities (Grants 04/07309, 09/54672-4 and 10/50188-8 to RCC) and to CNPQ (Research Scholarships PQ 304784/2011-7 to RCC and 130837/2011-3 to JAFP). The authors are indebted to Mr. Antônio Fraga da Silva for indicating the sampling site and allowing the collections. We would also like to extend thanks to Dr. Maria Lucia Negreiros Fransozo and the anonymous reviewer for their extremely constructive comments on an earlier version of this manuscript; and to Dr. Célio Ubirajara Magalhães Filho (INPA – InstitutoNacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia) for the identification of shrimps. The prawns in this study were collected according to Brazilian laws concerning sampling of wild animals.

References

- ANGER, K., 2013. Neotropical Macrobrachium (Caridea: Palaemonidae): On the biology, origin, and radiation of freshwater-invading shrimp. Journal of Crustacean Biology, vol. 33, no. 2, p. 151-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1937240X-00002124.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1937240X-00002124 - ANGER, K. and HAYD, L., 2009. From lecithotrophy to planktotrophy: ontogeny of larval feeding in the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquatic Biology, vol. 7, no. 1/2, p. 19-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.3354/ab00180.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3354/ab00180 - ANGER, K., HAYD, L., KNOTT, U. and NETTELMANN, U., 2009. Patterns of larval growth and chemical composition in the Amazon River prawn, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 287, no. 3–4, p. 341-348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.10.042.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.10.042 - BAUER, RT., 2004. Remarkable shrimps: adaptations and natural history of the Carideans. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. 282 p.

- BIALETZKI, A., NAKATANI, K., BAUMGARTNER, RG. and BOND-BUCKUP, G., 1997. Occurrence of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller) (Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in Leopoldo's inlet (Ressaco do Leopoldo), upper Paraná River, Porto Rico, Paraná, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 379-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751997000200011.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751997000200011 - COELHO, PA. and RAMOS-PORTO, MR., 1984. Camarões de água doce do Brasil: distribuição geográfica. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 2, no. 6, p. 405-410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751984000200014.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751984000200014 - GUEST, WC., 1979. Laboratory life history of the palaemonid shrimp Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862) (Decapoda, Palaemonidae). Crustaceana, vol. 37, no. 2, p. 141-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156854079X00979.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156854079X00979 - HÅKANSON, L., 2005. Changes to lake ecosystem structure resulting from fish cage farm emissions. Lakes and Reservoirs: Research and Management, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 71-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1770.2005.00253.x.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1770.2005.00253.x - HAYD, L., ANGER, K. and VALENTI, WC., 2008. The moulting cycle of larval Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum reared in the laboratory. Nauplius, vol. 16, p. 55-63.

- HAYD, L. and ANGER, K., 2013. Reproductive and morphometric traits of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda: Palaemonidae) from the Pantanal, Brazil, suggests initial speciation. Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 61, no. 1, p. 39-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.10881. PMid:23894962

» http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v61i1.10881 - HOLTHUIS, LB., 1952. A general revision of the Palaemonidae (Crustacea Decapoda Natantia) of the Americas. II. The subfamily Palaemoninae. Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press. 396 p. (Allan Hancock Foundations Publications. Occasional Paper, no. 12).

- KURIS, AM., RA'ANAN, Z., SAGI, A. and COHEN, D., 1987. Morphotypic differentiation of male Malaysian giantprawns, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Journal of Crustacean Biology, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 219-237. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1548603.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1548603 - KUTTY, MN., 2005. Towards sustainable freshwater prawn aquaculture – lessons from shrimp farming, with special reference to India. Aquaculture and Research, vol. 36, no. 3, p. 255-263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01240.x.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01240.x - LOPEZ, B. and PEREIRA, G., 1996. Inventario de los crustáceos decapodos de las zonas alta y media del delta del Rio Orinoco, Venezuela. Acta Biologica Venezuelica, vol. 16, no. 3, p. 45-64.

- MACIEL, CR. and VALENTI, WC., 2009. Biology, fisheries, and aquaculture of the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum: a review. Nauplius, vol. 17, no. 2, p. 61-79.

- MAGALHÃES, C., 2000. Diversity and abundance of decapod crustaceans in the Rio Negro Basin, Pantanal, MatoGrosso do Sul, Brazil. In WILLINK, P., CHERNOFF, B., ALONSO, LE., MONTAMBAULT, J. and LOURIVAL, R., (Eds.). A biological assessment of the aquatic ecosystems of the Pantanal, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Washington: Conservation International. p. 56-62.

- MAGALHÃES, C., 2001. Diversity, distribution, and habitats of the macro-invertebrate fauna of the Rio Paraguay and Rio Apa, Paraguay, with emphasis on decapod crustaceans 6872. In CHERNOFF, B., WILLINK, PW. and MONTAMBAULT, JR. (Eds.). A Biological Assessment of the Aquatic Ecosystems of the Rio Paraguay Basin, Alto Paraguay, Paraguay. Washington: Conservation International. (RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment, no. 19).

- MAGALHÃES, C., 2002. A rapid assessment of the decapod fauna in the Rio Tahuamanu and Rio Manuripi Basins, with new records of shrimps and crabs for Bolivia (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae, Sergestidae, Trichodactylidae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 19, no. 4, p. 1091-1103.

- MAGALHÃES, C., BUENO, SLS., BOND-BUCKUP, G., VALENTI, WC., SILVA, HLM., KIYOHARA, F., MOSSOLIN, EC. and ROCHA, S., 2005. Exotic species of freshwater decapod crustaceans in the state of São Paulo, Brazil: records and possible causes of their introduction. Biodiversity and Conservation, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 1929-1945. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-2123-8.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-2123-8 - MARQUES, HLA. and MORAES-VALENTI, PMC., 2012. Current status and prospects of farming the giant river prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man 1879) and the Amazon river prawn (Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) in Brazil. Aquaculture and Research, vol. 43, no. 7, p. 984-992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2011.03032.x.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2011.03032.x - MASHIKO, K., 1983. Comparison of growth pattern until sexual maturity between the estuarine and upper freshwater populations of the prawn Macrobrachium nipponense (de Haan) within a river. Japanese Journal of Ecology, vol. 33, p. 207-212.

- MELO, GAS., 2003. Manual de Identificação dos Crustacea Decapoda de água doce do Brasil. São Paulo: Loyola. 429 p.

- MORAES-RIODADES, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2004. Morphotypes in male Amazon River Prawns, Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquaculture, vol. 236, no. 1-4, p. 297-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.015 - MORAES-VALENTI, P. and VALENTI, WC., 2010. Culture of the Amazon River Prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum. In NEW, MB., VALENTI, WC., TIDWELL, JH., D'ABRAMO, LR. and KUTTY, MN. (Eds.). Freshwater prawns: biology and farming. Chichester: Wiley. p. 485-501.

- MORAES-VALENTI, PMC., MORAES, PA., PRETO, BL. and VALENTI, WC., 2010. Effect of density on population development in the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum. Aquatic Biology, vol. 9, no. 3, p. 291-301. http://dx.doi.org/10.3354/ab00261.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3354/ab00261 - NEW, MB., 2005. Freshwater prawn farming: global status, recent research and a glance at the future. Aquaculture and Research, vol. 36, no. 3, p. 210-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01237.x.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01237.x - ODINETZ-COLLART, O., 1987. La peche crevettiere de Macrobrachium amazonicum (Palaemonidae) dansleBas-Tocantins apreslafermeturedubarrage de Tucurui (Bresil). Revue d'Hydrobiologie Tropicale, vol. 20, no. 2, p. 131-144.

- ODINETZ-COLLART, O., 1988. Aspectos ecologicos do camarão Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862) no Baixo Tocantins (PA-Brasil). Memoria Sociedad de Ciencias Naturales La Salle, vol. 48, Supl., p. 341-353.

- ODINETZ-COLLART, O., 1993. Ecologia e potencial pesqueiro do camarão-canela Macrobrachium amazonicum na Bacia Amazônica. In FERREIRA. EJG., SANTOS, GM., LEÃO, ELM. and OLIVEIRA, LA. (Eds.). bases científicas para estratégias de preservação e desenvolvimento da amazônia: fatos e perspectivas. Manaus: INPA. p. 147-166. vol. 2.

- ODINETZ-COLLART, O. and MOREIRA, LC., 1993. Potencial pesqueiro de Macrobrachium amazonicum na Amazônia Central (Ilha do Careiro): variação da abundância e do comprimento. Amazoniana, vol. 12, no. 3-4, p. 399-413.

- PANTALEÃO, JAF., HIROSE, GL. and COSTA, RC., 2012. Relative growth, morphological sexual maturity, and size of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller 1862) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in a population with an entirely freshwater life cycle. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, vol. 56, no. 3, p. 180-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2011.587276 - PAPA, LP., FRANCESCHINI-VICENTINI, IB., VICENTINI, CA. and PEZZATO, LE., 2004. Diferenciação morfotípica de machos do camarão de água doce Macrobrachium amazonicum a partir da análise do hepatopâncreas e do sistema reprodutor. ActaSientiarium. Animal Science, vol. 26, no. 4, p. 463-467.

- PETTOVELLO, AD., 1996. First record of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda, Palaemonidae) in Argentina. Crustaceana, vol. 69, no. 1, p. 113-114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156854096X00141.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156854096X00141 - PRETO, BL., KIMPARA, JM., MORAES-VALENTI, PMC. and VALENTI, WC., 2010. Population structure of pond-raised Macrobrachium amazonicum with different stocking and harvesting strategies. Aquaculture, vol. 307, no. 3-4, p. 206-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2010.07.023.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2010.07.023 - RAMOS, IP., VIDOTTO-MAGNONI, AP. and CARVALHO, ED., 2008. Influence of cage fish farming on the diet of dominant fish species of a Brazilian reservoir (Tietê River, High Paraná River basin). Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia, vol. 20, no. 3, p. 245-252.

- ROBE, LJ., MACHADO, S. and BARTHOLOMEI-SANTOS, ML., 2012. The DNA barcoding and the caveats with respect to its application to some species of Palaemonidae (Crustacea, Decapoda). Zoological Science, vol. 29, no. 10, p. 714-724. http://dx.doi.org/10.2108/zsj.29.714. PMid:23030345

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2108/zsj.29.714 - RODRIGUEZ, G., 1982. Fresh-water shrimps (Crustacea, Decapoda, Natantia) of the Orinoco basin and the Venezuelan Guayana. Journal of Crustacean Biology, vol. 2, no. 3, p. 378-391. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1548054.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1548054 - SANTOS, JA., SAMPAIO, CMS. and SOARES-FILHO, AA., 2006. Male population structure of the Amazon River prawn (Macrobrachium amazonicum) in a natural environment. Nauplius, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 55-63.

- SILVA, GMF., FERREIRA, MAP., VON LEDEBUR, EICF. and ROCHA, RM., 2009. Gonadal structure analysis of Macrobrachium amazonicum (Heller, 1862) from a wild population: a new insight on the morphotype characterization. Aquaculture and Research, vol. 40, no. 7, p. 798-803. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2009.02165.x.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2009.02165.x - THIEL, M., SOLOMON, TCC. and DUMONT, CP., 2010. Male Morphotypes and Mating Behavior of the Dancing Shrimp Rhynchocinetesbrucei (Decapoda: Caridea). Journal of Crustacean Biology, vol. 30, no. 4, p. 580-588. http://dx.doi.org/10.1651/09-3272.1.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1651/09-3272.1 - TORLONI, CEC., SANTOS, JJ., CARVALHO, AAJR. and CORRÊA, ARA., 1993. A pescada-do-Piauí Plagioscionsquamosissimus (Heckel, 1840) (Osteichthyes, Perciformes) nos reservatórios da Companhia Energética de São Paulo – CESP. São Paulo: CESP. p. 1-23. Série Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento, vol. 84.

- VALENCIA, DM. and CAMPOS, MR., 2007. Freshwater prawns of the genus Macrobrachium Bate, 1868 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae) of Colombia. Zootaxa, vol. 1456, p. 1-44.

- VALENTI, WC., 1998. Carcinicultura de água doce: tecnologia para produção de camarões. Brasília: IBAMA. 383 p.

- VERGAMINI, FG., PILEGGI, LA. and MANTELATTO, FL., 2011. Genetic variability of the Amazon River prawn Macrobrachium amazonicum (Decapoda, Caridea, Palaemonidae). Contributions to Zoology, vol. 80, no. 1, p. 67-83.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Aug 2014

History

-

Received

19 Mar 2013 -

Accepted

5 June 2013 -

Reviewed

30 Nov 2014