Abstracts

Most natural forests have been converted for human use, restricting biological life to small forest fragments. Many animals, including some species of bats are disappearing and the list of these species grows every day. It seems that the destruction of the habitat is one of its major causes. This study aimed to analyze how this community of bats was made up in environments with different sizes and quality of habitat. Data from studies conducted in the region of Londrina, Parana, Brazil, from 1982 to 2000 were used. Originally, this area was covered by a semi deciduous forest, especially Aspidosperma polyneuron (Apocynaceae), Ficus insipida (Moraceae), Euterpe edulis (Arecaceae), Croton floribundus (Euforbiaceae), and currently, only small remnants of the original vegetation still exist. The results showed a decline in the number of species caught in smaller areas compared to the largest remnant. In about 18 years of sampling, 42 species of bats were found in the region, representing 67% of the species that occur in Paraná and 24.4% in Brazil. There were two species of Noctilionidae; 21 of Phyllostoma; 11 Vespertilionidae and eight Molossidae. Eight of these were captured only in the largest fragment, Mata dos Godoy State Park (680 ha). Ten species had a low capture rate in the smaller areas with less than three individuals. Of the total sampled, 14 species were found in human buildings, and were able to tolerate modified environments, foraging and even using them as shelter. As the size of the forest area increases, there is a greater variety of ecological opportunities and their physical conditions become more stable, i.e., conditions favorable for growth and survival of a greater number of species. Forest fragmentation limits and creates subpopulations, preserving only long-lived K-strategist animals for some time, where the supporting capacity of the environment is a limiting factor. The reduction of habitats, species and genetic diversity resulting from human activities are endangering the future adaptability in natural ecosystems, which promotes the disappearance of low adaptive potential species.

bat conservation; habitat destruction; wildlife elimination; human impact; forest fragments

A maior parte das florestas naturais foi convertida para uso humano, confinando a vida biológica a pequenos fragmentos florestais. Muitos animais, dentre os quais algumas espécies de morcegos, encontram-se em vias de desaparecimento e a lista dessas espécies aumenta a cada dia, sendo a destruição dos habitats um dos principais responsáveis por esse quadro. O objetivo deste trabalho foi analisar a composição da comunidade de morcegos em ambientes com diferentes tamanhos e qualidade de habitat; para isso, foram utilizados dados de trabalhos realizados na região de Londrina - Paraná, Brasil, entre os anos de 1982 e 2000. Originalmente, essa área era coberta por floresta estacional semidecidual, com destaque para Aspidosperma polyneuron (Apocynaceae), Ficus insipida (Moraceae), Euterpe edulis (Arecaceae) e Croton floribundus (Euforbiaceae); nota-se que, atualmente, restam apenas pequenos remanescentes da vegetação original. Os resultados mostraram um declínio no número de espécies capturadas nas áreas de menor tamanho em relação ao maior remanescente. Em aproximadamente 18 anos de amostragens, 42 espécies de morcegos foram encontradas na região, o que representa 67% das espécies que ocorrem no Paraná e 24,4% no Brasil, sendo duas espécies de Noctilionidae, 21 de Phyllostomidade, 11 de Vespertilionidae e oito de Molossidae. Destas, oito foram capturadas apenas no maior fragmento, o Parque Estadual Mata dos Godoy (680 ha). Dez espécies apresentaram baixo índice de captura nas menores áreas, com menos de três indivíduos. Do total amostrado, 14 espécies foram encontradas em edificações humanas, sendo capazes de tolerar ambientes modificados, forrageando e até mesmo utilizando-os como abrigo. Conforme o tamanho da área de floresta aumenta, há uma maior variedade de oportunidades ecológicas e suas condições físicas tornam-se mais estáveis, ou seja, há condições favoráveis para o crescimento e a sobrevivência de um maior número de espécies. A fragmentação florestal limita e cria subpopulações, preservando somente por algum tempo um animal de vida longa, K-estrategista, em que a capacidade suporte do meio é um fator restritivo. A redução dos habitats, das espécies e da diversidade genética resultante das atividades humanas está pondo em risco a adaptabilidade futura nos ecossistemas naturais, o que promove o desaparecimento de espécies de baixo potencial adaptativo.

preservação de morcegos; destruição de habitats; eliminação da vida selvagem; impacto humano; fragmentos florestais

ECOLOGY

Sensitivity of populations of bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in relation to human development in northern Paraná, southern Brazil

Sensibilidade das populações de morcegos (Mammalia: Chiroptera) frente ao desenvolvimento humano no norte do Paraná, sul do Brasil

Reis, NR.I,* * e-mail: nrreis1@yahoo.com.br ; Gallo, PH.II; Peracchi, AL.III; Lima, IP.III; Fregonezi, MN.IV

IDepartamento de Biologia Animal e Vegetal, Universidade Estadual de Londrina UEL, CEP 86051-990, Londrina, PR, Brazil

IIPrograma de Pós-graduação em Ecologia de Ambientes Aquáticos Continentais, Universidade Estadual de Maringá UEM, CEP 87020-900, Maringá, PR, Brazil

IIILaboratório de Mastozoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro UFRRJ, CEP 23851-970, Seropédica, RJ, Brazil

IVPrograma de Pós-graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Londrina UEL, CEP 86051-970, Londrina, PR, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Most natural forests have been converted for human use, restricting biological life to small forest fragments. Many animals, including some species of bats are disappearing and the list of these species grows every day. It seems that the destruction of the habitat is one of its major causes. This study aimed to analyze how this community of bats was made up in environments with different sizes and quality of habitat. Data from studies conducted in the region of Londrina, Parana, Brazil, from 1982 to 2000 were used. Originally, this area was covered by a semi deciduous forest, especially Aspidosperma polyneuron (Apocynaceae), Ficus insipida (Moraceae), Euterpe edulis (Arecaceae), Croton floribundus (Euforbiaceae), and currently, only small remnants of the original vegetation still exist. The results showed a decline in the number of species caught in smaller areas compared to the largest remnant. In about 18 years of sampling, 42 species of bats were found in the region, representing 67% of the species that occur in Paraná and 24.4% in Brazil. There were two species of Noctilionidae; 21 of Phyllostoma; 11 Vespertilionidae and eight Molossidae. Eight of these were captured only in the largest fragment, Mata dos Godoy State Park (680 ha). Ten species had a low capture rate in the smaller areas with less than three individuals. Of the total sampled, 14 species were found in human buildings, and were able to tolerate modified environments, foraging and even using them as shelter. As the size of the forest area increases, there is a greater variety of ecological opportunities and their physical conditions become more stable, i.e., conditions favorable for growth and survival of a greater number of species. Forest fragmentation limits and creates subpopulations, preserving only long-lived K-strategist animals for some time, where the supporting capacity of the environment is a limiting factor. The reduction of habitats, species and genetic diversity resulting from human activities are endangering the future adaptability in natural ecosystems, which promotes the disappearance of low adaptive potential species.

Keywords: bat conservation, habitat destruction, wildlife elimination, human impact, forest fragments.

RESUMO

A maior parte das florestas naturais foi convertida para uso humano, confinando a vida biológica a pequenos fragmentos florestais. Muitos animais, dentre os quais algumas espécies de morcegos, encontram-se em vias de desaparecimento e a lista dessas espécies aumenta a cada dia, sendo a destruição dos habitats um dos principais responsáveis por esse quadro. O objetivo deste trabalho foi analisar a composição da comunidade de morcegos em ambientes com diferentes tamanhos e qualidade de habitat; para isso, foram utilizados dados de trabalhos realizados na região de Londrina - Paraná, Brasil, entre os anos de 1982 e 2000. Originalmente, essa área era coberta por floresta estacional semidecidual, com destaque para Aspidosperma polyneuron (Apocynaceae), Ficus insipida (Moraceae), Euterpe edulis (Arecaceae) e Croton floribundus (Euforbiaceae); nota-se que, atualmente, restam apenas pequenos remanescentes da vegetação original. Os resultados mostraram um declínio no número de espécies capturadas nas áreas de menor tamanho em relação ao maior remanescente. Em aproximadamente 18 anos de amostragens, 42 espécies de morcegos foram encontradas na região, o que representa 67% das espécies que ocorrem no Paraná e 24,4% no Brasil, sendo duas espécies de Noctilionidae, 21 de Phyllostomidade, 11 de Vespertilionidae e oito de Molossidae. Destas, oito foram capturadas apenas no maior fragmento, o Parque Estadual Mata dos Godoy (680 ha). Dez espécies apresentaram baixo índice de captura nas menores áreas, com menos de três indivíduos. Do total amostrado, 14 espécies foram encontradas em edificações humanas, sendo capazes de tolerar ambientes modificados, forrageando e até mesmo utilizando-os como abrigo. Conforme o tamanho da área de floresta aumenta, há uma maior variedade de oportunidades ecológicas e suas condições físicas tornam-se mais estáveis, ou seja, há condições favoráveis para o crescimento e a sobrevivência de um maior número de espécies. A fragmentação florestal limita e cria subpopulações, preservando somente por algum tempo um animal de vida longa, K-estrategista, em que a capacidade suporte do meio é um fator restritivo. A redução dos habitats, das espécies e da diversidade genética resultante das atividades humanas está pondo em risco a adaptabilidade futura nos ecossistemas naturais, o que promove o desaparecimento de espécies de baixo potencial adaptativo.

Palavras-chave: preservação de morcegos, destruição de habitats, eliminação da vida selvagem, impacto humano, fragmentos florestais.

1. Introduction

Most of the land with natural vegetation has been converted for human use, restricting biological life to small forest fragments surrounded by agricultural land or cities. This situation is constantly aggravated due to the growing needs of food production and energy consumption (Miller Junior, 2007).

This process has consequences for animal populations that remain in these areas, such as diminished food supplies, increased inbreeding and a reduced size of the life area (Reis et al., 2003). For most organisms, habitat destruction and modification have been gradual, where the local population is declining and the impacts are perceived only when species disappear from a significant part of the original habitat (Hero and Ridgway, 2006). Many animals, among them bats, are disappearing (eight endangered species) (Chiarello et al., 2008) and the list of these species has increased, and the destruction of a habitat is one of its major causes (Primack, 2006).

Agricultural industrialization and the use of insecticides have caused the bat populations to decline rapidly from the middle of the last century (Neuweiler, 2000). According to Wickramasinghe et al. (2003), the increased use of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides and growth regulators may be factors that determine the presence or absence of many species of bats in a natural ecosystem.

In the north of Paraná, where activities related to agriculture and livestock are widespread in terms of fertile soils, there is only 2 to 4% of the original ecosystem, represented by small remnants surrounded by areas of intensive farming (Torezan, 2002; Reis et al., 2006a). Originally, the entire surface of the state of Parana, about 201,203 km2, was covered by different types of vegetation (Reis et al., 2002). This vegetation was almost totally destroyed, leaving large areas of forests only in the western state (Iguaçu National Park) and in the Serra do Mar (Reis et al., 2008).

The Atlantic Forest has been identified as a risk area to Biodiversity (Mittermeier et al., 1998; Myers et al., 2000) and in addition to housing some of the world's rarest species, the atlantic remnants are directly associated with human quality of life, since forests are vital for watershed protection, soil erosion and to maintain the environmental conditions necessary for the existence of cities and rural areas (Di Bitetti et al., 2003).

Some populations of bats survive due to some remaining forest fragments within the inhabited world and it is believed that the size of the forest fragment is important to keep a larger number of species (Chiarello, 2000; Reis et al., 2003). Some work related to communities in forest remnants show that the smaller the size of the fragment, the greater the changes (Marinho-Filho and Sazima, 1998; Cosson et al., 1999; Félix et al., 2001; Bianconi et al., 2004; Esbérard, 2009; Ortêncio-Filho and Reis, 2009; Gallo et al., 2010).

This study aims to analyze how a community of bats was made up in areas with different sizes and quality by observing the presence and absence of species and their decline in recent decades due to anthropogenic activities.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Area of study

The city of Londrina has an area of 2,119 km², located at coordinates 23º 23' 30" S and 51º 11' 05" W. It has an average altitude of 700 m and humid subtropical climate according to Köppen. It has rainfall in all seasons, with an annual average of 1.615 mm. The wettest months are December and January, and the lowest rainfall in August. The maximum temperature is 39 ºC and the minimum is 10.4 ºC (Iapar, 1994).

For this paper, we considered data from surveys conducted between 1982 and 2000 (Muller and Reis, 1992; Reis et al., 1993a, b, 1998, 2000, 2006a, b; Reis and Muller, 1995; Félix et al., 2001) in eight forest remnants in the region of Londrina: Mata dos Godoy State Park (680 ha), Arthur Thomas Municipal Park (85.47 ha); Horto Florestal at the State University of Londrina (10 ha); forest fragment at Regina farm (6.2 ha), municipality of Sertanópolis; valley bottom of the city of Londrina (4 ha); Coimbra forest (2 ha) and Vitória ranch (1 ha), both located in Londrina (see Figure 1).

The Mata do Godoy State Park (PEMG) is considered fairly large, located outside the city limits of Londrina and features a continuous vegetation cover in good preservation, with examples of flora and fauna from northern Paraná. It is the last reserve of primary forest in the region and is surrounded by farmland. The Ribeirão Apertados is the only perennial stream of the park, bordering its south side and crossed by the Tropic of Capricorn. The park is covered in almost its entire length by semi deciduous forest, especially Aspidosperma polyneuron ("pink mahogany"), Ficus insipida ("white fig tree"), Euterpe edulis ("palmetto"), Croton floribundus ("capixingui"), Nectandra megapotamica ("black cinnamon") (Chagas e Silva and Soares-Silva, 2000). Morace, Solanaceae and Piperaceae are common on the banks of the forest. In this area, work was carried out between 1982 and 1999.

The Municipal Park Arthur Thomas (PMAT), located within the city of Londrina, has a total area of 85.47 ha and 67.12 ha of remaining forest, consisting of altered primary vegetation (Maack, 2002). It is cut by the Cambé stream surrounded by man-altered environments. Its greatest extent is covered by altered semi deciduous forest, housing species such as A. polyneuron, Gallesia integriofolia ("pau-d'alho"), Chorisia speciosa ("paineira"), Cabralea canjerana ("canjarana"), P. rigida ("angico vermelho"; "gurucaia"), Ficus sp. ("Fig trees"), Syagrus romanzoffiana ("jerivá") (Félix et al., 2001). According to Cotarelli et al. (2008), the most representative genus are the Solanum (16 genera), Piper (10), Ipomoea (8), Vernonia (7) and, Eupatorium and Miconia (6).

The five fragments of small sizes have an average of 4 ha, totaling 20 ha. The Horto Florestal at the State University of Londrina is located on the University Campus, at km 379 of Highway Celso Garcia Cid and is approximately 5 km from the city center, formed by secondary vegetation. The valley bottom of the city of Londrina, the Coimbra forest, Vitória ranch and Regina farm are also formed by secondary vegetation, sheltering a few representatives of the native forest. There are some pioneer species, as well as fruit trees such as Carica papaya ("papaya") Diospyros kaki ("khaki"), Persea americana ("avocado"), Morus nigra ("blackberry"), Psidium guajava ("guava"); Plinia trunciflora ("jabuticaba") and Eriobotrya japonica ("plum") (Brummitt, 1992). The five fragments mentioned above are considered altered because they are surrounded by pastures, agriculture and environments having strong anthropogenic pressure.

2.2. Data collection

The capture techniques were adapted from those by Greenhall and Paradiso (1968) and Reis (1984). Mist nets were used and were set up 0.5 to 2.5 m above the ground on roads with little traffic, in clearings within the forest, across streams and in the resting places of bats. For methodological description see Muller and Reis (1992), Reis et al. (1993a, b, 1998, 2000, 2006a, b) and Félix et al. (2001). Daytime catches were performed according to Bredt et al. (1996), where they visited sites used by bats for shelter (the lining of homes and buildings, expansion joints, drains, cracks in rocks, among others).

2.3. Identification of bats

Bats were identified according to criteria by Vizotto and Taddei (1973), Reis et al. (1993a) and their identifications were confirmed in the Mastozoology laboratory of the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro, by Professor. Dr. Adriano Lúcio Peracchi and deposited in the collection of this university.

3. Results

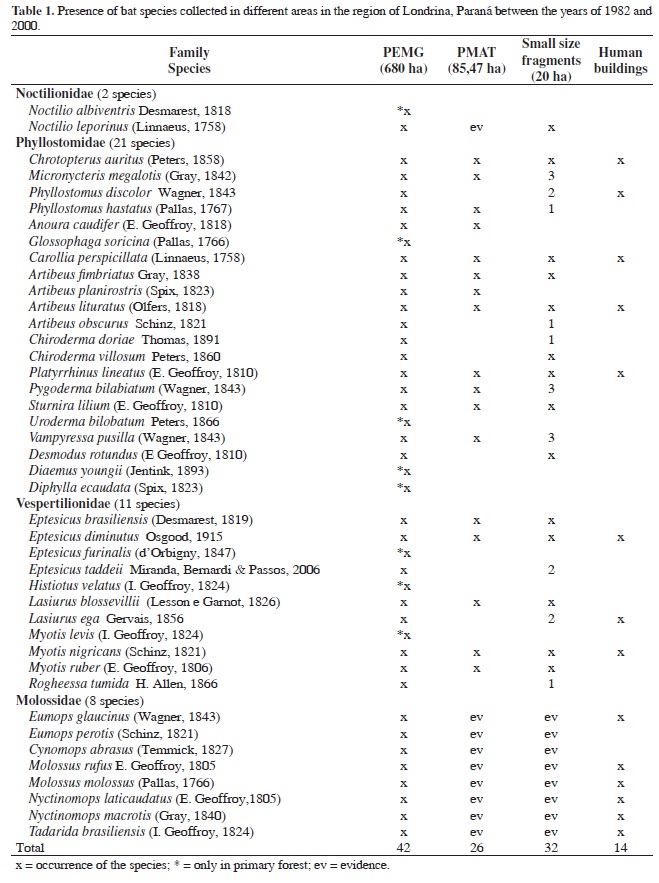

In about 18 years of sampling, 42 species of bats have been found in the preserved primary forest of 680 ha (PEMG), distributed in the families Noctilionidae, Phyllostomidae, Vespertilionidae and Molossidae. Eight species were unique to this area. In the medium-sized remnant, which has 67.12 ha of remaining forest (PMAT), 26 species were found. In the five smaller fragments that have an average of 4 ha ( Horto Florestal UEL; Regina farm; Valley bottom; Mata Coimbra and Vitoria ranch), 33 species were recorded in total of which N. leporinus (Linnaeus, 1758) and Phyllostomus discolor Wagner, 1843 were found only in these areas (Table 1). On Regina farm there was a record of the species Chiroderma doriae Thomas, 1891 which is on the List of Endangered Species in category "data deficient" and the "least concern" by the IUCN (2010).

Twelve species were found both in the area considered most preserved (PEMG), and in smaller fragments and urban buildings and six were very common in small fragments. Ten species were very little captured, having a number equal to or less than three individuals. In human buildings, 14 species were captured, nine insectivorous, and of these, six belong to the family Molossidae. Only three species were found in shelters with more than 100 individuals (Molossus rufus E. Geoffroy, 1805, Molossus molossus (Pallas, 1766) and Tadarida brasiliensis (I. Geoffroy, 1824).

4. Discussion

This paper does not deal with abundant or rare species, but with little or very collected species, in primitive and/or altered areas, and is a way to differentiate the species best adapted to the impacted areas, from the most sensitive ones.

In the Mata dos Godoy State Park (680 ha), 42 bat species were sampled, representing 67% of the species that occur in Paraná and 24.4% in Brazil (Reis et al., 2007). As it is a primary fragment, it provides niche spaces with many dimensions and hence a greater number of species can be grouped, which reduces the asymmetry of competition (Ricklefs, 2003). The highest diversity of bats in conserved areas was observed by Fenton (2002), where species use different niches, compared to affected areas. Well-structured and less-impacted areas can concentrate a higher amount of useful resources for bats (Erickson and West, 2003).

A remnant of a reasonable size fosters an appropriate environment concerning temperature, humidity, noise, wind, generating at its core, ideal conditions for growth and survival of a greater number of species (Zannon and Reis, 2009), as some bats are dependent on stable conditions (Findley, 1993). Moreover, cross-fertilization rates are higher, reducing the genetic resistance of species (Stearns and Hoekstra, 2003), receiving a higher amount of solar energy by increasing rates of productivity (Dajóz, 2005). As the size of the forest area increases, there is a greater variety of ecological opportunities and their physical conditions become more stable and therefore safer (Ricklefs, 2003).

Disturbingly, seven species were collected exclusively in the larger-sized area and not in smaller and not changed areas (N. albiventris, U. bilobatum, D. youngii, D. ecaudata, E. furinalis, H. velatus and M. Levis), and they can be considered more sensitive. Without this area, they would decrease dramatically in number or even disappear. In this group, ten could be included that were only found in small fragments, equally or a fewer number than three individuals (P. discolor, P. hastatus, A. caudifer. C. doriae and C. villosum, P. bilabiatum, V. pussila, E. taddeii, L. ega and R. tumida). These 18 species can be considered a risk group.

According to Ricklefs (2003), as the environment undergoes changes, some species disappear and others take their place. Thus, background extinction occurs. Although diversity in altered biotic communities is reduced (Odum and Barrett, 2007), species such as C. perspicillata , P. lineatus, A. lituratus and S. lilium, found in all studied areas (large forests, small fragments and human habitations), show a high adaptive potential for the use of modified environments - a fact related to the general habits of habitat use and the ability to reproduce throughout the year (Nowak, 1994), and their preferences for pioneer and edgy vegetation.

Although some species can adapt themselves, most populations of small fragments are more vulnerable, mainly by staying reduced, and losing the genetic variability of chance (Olifiers and Cerqueira, 2006; Pires et al., 2006). By reducing populations, there is a decrease in active individuals and consequently, in the variations in reproduction and mortality rates affecting the continuity of the population (Primack et al., 2001). Therefore, they are more vulnerable to random fluctuations and increase susceptibility to environmental variations. Thus, the combination of changes in genetic variability, environmental and demographic variation in small populations creates distinct mechanisms that tend to undermine the success of the species.

When large extensions of native forest are reduced to impacted areas, we note that the conservation of total biodiversity depends on few individual species. Especially when considering K-strategist populations, in which the supporting capacity of the medium is a limiting factor, and which tends to prepare their offspring to compete for food and space, and have longer lifetime in contrast with R-strategists individuals (Pianka, 1994; Bassanezi, 2002).

Bats belonging to the family Molossidae, which were found in human buildings, have a similar structure and function under the conditions that shape their new environment, i.e., in urban centers, where they are closer to large concentrations of insects due to the higher incidence of light (Begon et al., 2007).

Environmental changes, besides causing the decline in the number of species, promote the loss of important elements in different trophic levels and changes in the structure and functioning of the ecosystem, resulting in simplifying the structure of assemblages of different species including bats (Aguiar, 1994).

The distance between the fragments can prevent the dispersal of bats to more favorable locations, especially for those who are unable to travel long distances (Cosson et al., 1999) and those that require specific shelters. Since bats have a real capacity of flight, it is possible that they cover large distances in a short period of time, as is the case of A. lituratus, C. perspicillata , S. lilium (Bernard and Fenton, 2003; Esbérard, 2003; Bianconi et al., 2006) and many Molossidae.

However, in relation to the movement, some species have been shown to be sensitive to habitat fragmentation (Bernard and Fenton, 2007; Meyer et al., 2008). Albrecht et al. (2007) analyzed the mobility of two species of small-sized phyllostomid, one belonging to the genus Micronycteris which showed sedentary behavior. Species such as M. megalotis, C. doriae, P. bilabiatum, V. pusilla, E. taddeii, L. ega and R. tumida may not be moving between areas, because of the low number of catches observed.

The probability of extinction of a species depends not only on the intrinsic properties of each one (birth and death rates, etc.), but also the interactions with other species in the community, such as competitors, predators, parasites and mutualists (Begon et al., 2007). In addition, studies show the importance of primary forests, the presence of water bodies and locations used as shelters for the population of bats (Reis et al., 2003; Bondarenco, 2009). According to Primack and Rodrigues (2001), a population that shows signs of decline will probably be extinguished if the cause of this process is not identified and corrected. Despite several studies showing that reductions of natural habitats decreased the number of species, what has been done so that people know the importance of this group? And what law has been enforced so that it can protect a group, which is gradually disappearing?

Received July 20, 2011

Accepted October 5, 2011

Distributed August 31, 2012

- AGUIAR, LMS., 1994. Comunidades de Chiroptera em três áreas da Mata Atlântica em diferentes estádios de sucessão: estação Biológica de Caratinga. Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. 90 p. Dissertação de Mestrado.

- ALBRECHT, L., MEYER, CFJ. and KALKO, EKV., 2007. Differential mobility in two small phyllostomid bats, Artibeus watsoni and Micronycteris microtis, in a fragmented neotropical landscape. Acta Theriologica, vol. 52, no. 2, p. 141-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03194209

- BASSANEZI, RC., 2002. Ensino: aprendizagem com modelagem matemática. São Paulo: Contexto. 389 p.

- BEGON, M., TOWNSEND, CR. and HARPER, JL., 2007. Ecologia: de indivíduos a ecossistemas. 4. ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed. 752 p.

- BERNARD, E. and FENTON, MB., 2003. Bat mobility and roosts in a fragmented landscape in Central Amazonia, Brazil. Biotropica, vol. 35, no. 2, p. 262-277.

- -, 2007. Bats in a fragmented landscape: species composition, diversity and habitat interactions in savannas of santarem, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Biological Conservation, vol. 134, no. 3, p. 332-343. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2006.07.021

- BIANCONI, GV., MIKICH, SB. and PEDRO, WA., 2004. Diversidade de morcegos (Mammalia, Chiroptera) em remanescentes florestais do município de Fênix, noroeste do Paraná, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 21, no. 4, p. 943-954.

- -, 2006. Movementsofbats (Mammalia, Chiroptera) in Atlantic Forest remnants in southernBrazil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 23, no. 4, p. 1199-1206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81752006000400030

- BONDARENCO, A., 2009. Seasonal variations in distribution patters and movements of bats in relation to habitat characteristics International Master Programme at the Swedish Biodiversity Centre. 40 p. Dissertation.

- BREDT, AI., ARAÚJO, FAA., CAETANO-JUNIOR, J., RODRIGUES, MGR., YOSHIZAWA, M., SILVA, MMS., HARMANI, NMS., MASSUNAGA, PNT., BURER, SP., POTRO, VAR. and UIEDA, W., 1996. Morcegos em áreas urbanas e rurais: manual de manejo e controle. Brasília: Fundação Nacional de Saúde, Ministério da Saúde. 117 p.

- BRUMMIT, RK., 1992. Vascular plant families and genera Kew, Royal Botanic Gardens. 800 p.

- CHAGAS E SILVA, F. and SOARES-SILVA, LH., 2000. Arboreal flora of the Godoy Forest State Park, Londrina, PR. Brazil. Edinburgh Journal of Botany, vol. 57, no. 1, p. 107-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S096042860000007X

- CHIARELLO, AG., 2000. Density and population size of mammals remnants of Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Conservation Biology, vol. 14, no. 6, p. 1649-1657. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99071.x

- CHIARELLO, AG., AGUIAR, LMS., CERQUEIRA, R., MELO, FR., RODRIGUES, FHG. and SILVA, VMF. 2008. Mamíferos Ameaçados de Extinção no Brasil. In MACHADO, ABM., DRUMMOND, GM. and PAGLIA, AP. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção Brasília: MMA, Belo Horizonte, Fundação Biodiversitas. p. 680-880.

- COSSON, JF., PONS, JM. and MASSON, D., 1999. Effects off orest fragmentation onfrugivorous and nectarivorous bats in French Guiana. Journal of Tropical Ecology, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 515 -534. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S026646749900098X

- COTARELLI, VM., VIEIRA, AOS., DIAS, M. C. and DOLIBAINA, PC., 2008. Florística do Parque Municipal Arthur Thomas, Londrina, Paraná, Brasil. Acta Biológica Paranaense, vol. 37, no. 1, 2, p. 123-146.

- DAJÓZ, R. 2005. Princípios de Ecologia Porto Alegre: Artmed. 520 p.

- DI BITETTI, MS., PLACCI, G. and DIETZ, LA., 2003. Uma visão de Biodiversidade para a Ecorregião Florestas do Alto Paraná Bioma Mata Atlântica: planejando a paisagem de conservação da biodiversidade e estabelecendo prioridades para ações de conservação. Washington: World Wildlife Fundation. 153 p.

- ERICKSON, JL. and WEST, SD., 2003. Associations of bats with local structure and landscape features of forested stands in western Oregon and Washington. Biological Conservation, vol. 109, p. 95-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00141-6

- ESBÉRARD, CEL., 2003. Marcação e deslocamento em morcegos. Divulgação do Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia, vol. 2, p. 23-24.

- -, 2009. Diversidade de morcegos em área de Mata Atlântica regenerada no sudeste do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoociências, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 189-204.

- FÉLIX, JS., REIS, NR., LIMA, IP., COSTA, EF. and PERACCHI, AL., 2001. Isthearea of the Arthur Thomas Park, with its 82. 72ha, sufficient to maintain viable chiropteran populations? Chiroptera Neotropical, vol. 7, no. 1, 2, p. 129-133.

- FENTON, MB., ACHARYA, L., AUDET, D., HICKEY, MBC., MERRIMAN, C., OBRIST, MK., SYME, DM. and ADKINS, B., 1992. Phyllostomid bats (Chiroptera, Mammalia) as indicators of habitat disruption in the Neotropics. Biotropica, vol. 24, no. 3, p. 440-446. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388615

- FINDLEY, JS., 1993. Bats: a community perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press. 179 p.

- GALLO, PH., REIS, NR., ANDRADE, FR. and ALMEIDA, IG., 2010. Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in native and reforested areas in Rancho Alegre, Paraná, Brazil. Revista de Biología Tropical , vol. 58, no. 4, p. 1311-1322. PMid:21246993.

- GREENHALL, AM. and PARADISO, JL., 1968. Bats and bat banding Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildllife Resource Publication. 67 p.

- HERO, JM. and RIDGWAY, T., 2006. Declínio Global de Espécies. In ROCHA, CFD., BERGALLO, HG., SLUYS, MV. and ALVES, MAS. Biologia da Conservação: Essências. RiMa, p. 53-90.

- Instituto Agronômico do Paraná - IAPAR. 1994. Cartas climáticas do estado do Paraná Londrina: IAPAR.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature – IUCN, 2010. The Red List of Threatened Species Available from: <http://www.iucnredlist.org/>

- MAACK, R. 2002. Geografia física do Estado do Paraná. 3. ed. Curitiba: Imprensa Oficial Paraná. 440 p.

- MARINHO-FILHO, J. and SAZIMA, I., 1998. Brazilian bats and conservation biology: a first survey. In KUNZ, TH. and RACEY, PA. Bat Biology and Conservation Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 282-294.

- MEYER, CFJ., FRÜND, J., LIZANO, WP. and KALKO, EKV., 2008. Ecological correlates of vulnerability to fragmentation in Neotropical bats. Journal of Applied Ecology, vol. 45, p. 381-391.

- MILLER JUNIOR, GT., 2007. Ciência Ambiental São Paulo: Thonsom Learning. 568 p.

- MITTERMEIER, RA., MYERS, N., THOMSEN, JB., DA FONSECA, GAB. and OLIVIERI, S., 1998. Biodiversity hotspots and major tropical wilderness areas: approaches to setting conservation priorities. Conservation Biology, vol. 12, p. 516-520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.012003516.x

- MULLER, MF. and REIS, NR., 1992. Partição de recursos alimentares entre quatro espécies de morcegos frugívoros (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 9, no. 3-4, p. 345-355.

- MYERS, N., MITTERMEIER, RA., MITTERMEIER, CG., DA FONSECA, GAB. and KEN, J., 2000. Biodiversityhotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, vol. 403, p. 853-858. PMid:10706275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/35002501

- NEUWEILER, G. 2000. The Biology of Bats New York: Oxford University Press. 310 p.

- NOWAK, RM., 1994. Walker's bats of the world Baltimore: Jonhs Hopkins University Press. 287 p.

- ODUM, EP. and BARRETT, GW., 2007. Fundamentos de Ecologia São Paulo: Thonsom Learning. 611 p.

- OLIFIERS, N. and CERQUEIRA, R., 2006. Fragmentação de habitats: Efeitos Históricos e Ecológicos. In ROCHA, CFD., BERGALLO, HG., SLUYS, MV. and ALVES, MV. Biologia da Conservação: Essências. RiMa. p. 261-279.

- ORTÊNCIO-FILHO, H. and REIS, NR., 2009. Species richness and abundance of bats in fragments of the stationalsemidecidual forest, Upper Paraná River, southern Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology, vol. 69, no. 2, p. 727-734. PMid:19738978.

- PIANKA, ER., 1994. Evolutionary ecology New York: Harper Collins. 365 p.

- PIRES, AS., FERNANDEZ, FAS. and BARROS, CS., 2006. Vivendo em um Mundo em Pedaços: Efeitos da fragmentação Florestal sobre Comunidades e Populações Animais. In ROCHA, CFD., BERGALLO, HG., SLUYS, MV. and ALVES, MV. Biologia da Conservação: Essências. RiMa. p. 231-260.

- PRIMACK, RB., 2006. Essentials of Conservation Biology 4th ed. Sinauer Associates. 585 p.

- PRIMACK, RB. and RODRIGUES, E., 2001. Ameaças à diversidade biológica. In PRIMACK, RB. and RODRIGUES, E. Biologia da Conservação Editora Planta. p. 69-134.

- PRIMACK, RB., ROZZI, R., FEINSINGER, P., DIRZO, R. and MASSARDO, F., 2001. Fundamentos de Conservación Biológica: perspectivas latino-americanas. México: FCE. 798 p.

- REIS, NR., 1984. Estrutura de comunidade de morcegos da região de Manaus, Amazonas. Revista Brasileira de Biologia = Brazilian Journal of Biology, vol. 44, p. 247-254.

- REIS, NR., BARBIERI, MLS., LIMA, IP. and PERACCHI, AL., 2003. O que é melhor para manter a riqueza de espécies de morcegos (Mammalia, Chiroptera): um fragmento florestal grande ou vários fragmentos de pequeno tamanho? Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 20, no. 2, p. 225-230.

- REIS, NR., LIMA, IP. and MIRETZKI, M., 2008. Morcegos do Paraná. In REIS, NR., PERACCHI, AL. and SANTOS, GASD. Ecologia de morcegos Technical Books. p. 143-148.

- REIS, NR., LIMA, IP. and PERACCHI, AL., 2006a. Morcegos (Chiroptera) da área urbana de Londrina, Paraná, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 19, no. 3, p. 739-746.

- REIS, NR. and MULLER, MF., 1995. Bat diversity of forests and open areas in a subtropical region of south Brazil. Ecologia Austral, vol. 5, p. 31-36.

- REIS, NR., MULLER, MF., SOARES, ES. and PERACCHI, AL., 1993a. Lista de quirópteros do Parque Estadual Mata dos Godoy e arredores de Londrina - Paraná. Revista Semina: Ciências Biológicas, Saúde, vol. 4, p. 120-126.

- REIS, NR., PERACCHI, AL. and LIMA, IP., 2002. Morcegos da Bacia do Rio Tibagi. In MEDRI, ME., BIANCHINI, E., SHIBATTA, OA. and PIMENTA, JA. A Bacia do Rio Tibagi Londrina. p. 251-270.

- REIS, NR., PERACCHI, AL., LIMA, IP. and PEDRO, WA. 2006b. Riqueza de espécie de morcegos (Mammalia, Chiroptera) em dois diferentes habitats, na região centro-sul do Paraná, sul do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 23, no. 3, p. 813-816.

- REIS, NR., PERACCHI, AL., LIMA, IP., SEKIAMA, ML. and ROCHA, VJ., 1998. Updated list of the chiropterans of the city of Londrina, Paraná, Brazil. Chiroptera Neotropical, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 96-98.

- REIS, NR., PERACCHI, AL. and ONUKI, MK. 1993b. Quirópteros de Londrina, Paraná, Brasil (Mammalia, Chiroptera). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 371-381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751993000300001

- REIS, NR., PERACCHI, AL., SEKIAMA, ML. and LIMA, IP., 2000. Diversidade de morcegos (Chiroptera: Mammalia) em fragmentos florestais no estado do Paraná, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 17, no. 3, p. 697-704.

- REIS, NR., SHIBATTA, OS., PERACCHI, AL., PEDRO, WA. and LIMA, IP., 2007. Sobre os Morcegos Brasileiros. In REIS, NR., SHIBATTA, OS., PERACCHI, AL., PEDRO, WA. and LIMA, IP.. Morcegos do Brasil Londrina. p. 17-26.

- RICKLEFS, RE., 2003. A economia da natureza 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan. 470 p.

- STEARNS, SC. and HOEKSTRA, RF., 2003. Evolução: uma introdução. São Paulo: Atheneu Editora. 379 p.

- TOREZAN, JMD., 2002. Nota sobre a vegetação da bacia do rio Tibagi. In MEDRI, ME., BIANCHINI, E., CHIBATTA, OA. and PIMENTA, JA. A bacia dorio Tibagi Londrina. p. 103-107.

- VIZOTTO, LD. and TADDEI, VA., 1973. Chave para determinação de quirópteros São José do Rio Preto: Gráfica Francal. 72 p.

- WICKRAMASINGHE, LP., HARRIS, S., JONES, G. and VAUGHAN, N., 2003. Bat activity and species richness on organic and conventional farms: impact of agricultural intensification. Journal of Applied Ecology, vol. 40, p. 984-993. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2003.00856.x

- ZANNON, CMV. and REIS, NR., 2009. O efeito de borda sobre os morcegos (Mammalia: Chiroptera) em um fragmento florestal Fazenda Unidas - Mato Grosso do Sul, BR. Revista Maquinações, vol. 1, p. 16.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

14 Sept 2012 -

Date of issue

Aug 2012

History

-

Received

20 July 2011 -

Accepted

05 Oct 2011