Abstracts

This article is concerned with the relationship between Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) and Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), and with SFL as a resource for socially accountable academic work. First it locates SFL within the general category of appliable linguistics (as opposed to either theoretical or applied linguistics), an approach to the study of language that is also designed to be socially accountable. Then, against the background of SFL, it traces the development first of Critical Linguistics and then of CDA, also identifying other influences incorporated within these traditions. Next, it compares CDA with other orientations within discourse analysis from the perspective of SFL, and proposes the notion of appliable discourse analysis (ADA). This leads to an overview of the dimensions of ADA, and finally to the question of the place of ADA within a general appliable linguistics.

Systemic Functional Linguistics; Appliable Linguistics; Critical Discourse Analysis; Critical Linguistics; Appliable Discourse Analysis

Este artigo diz respeito à Linguística Sistêmico Funcional (LSF) e Análise Crítica do discurso (ACD) e com a LSF como uma fonte de trabalho acadêmico socialmente justificável. Primeiro localiza a LSF dentro da categoria geral de Linguística aplicável (em oposição tanto a linguística teórica quanto aplicada), uma abordagem ao estudo da linguagem que também é designada como socialmente justificada. Portanto, com base na LSF traça o desenvolvimento primeiro da linguística crítica e depois da ACD, identificando também outras influências características dessas tradições. A seguir, compara a ACD com outras orientações dentro da análise do discurso na perspectiva de LSF, e propõe a noção de análise do discurso aplicável. Isto leva a uma visão geral da dimensão de ADA e finalmente à questão do lugar da ADA dentro de uma linguística geral aplicável.

Linguística Sistêmico Funcional; Linguistica Aplicável; Análise Crítica do Discurso; Linguística Crítica; Análise do Discurso Aplicável

ARTICLES

Systemic Functional Linguistics as appliable linguistics: social accountability and critical approaches1 1 . I am grateful to Leila Barbara and Abhishek Kumar for helpful comments on this paper.

LSF como linguistica aplicavel: explicatividade social e abordagens criticas

Christian M.I.M. Matthiessen

Universidade Politécnica de Hong Kong

ABSTRACT

This article is concerned with the relationship between Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) and Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), and with SFL as a resource for socially accountable academic work. First it locates SFL within the general category of appliable linguistics (as opposed to either theoretical or applied linguistics), an approach to the study of language that is also designed to be socially accountable. Then, against the background of SFL, it traces the development first of Critical Linguistics and then of CDA, also identifying other influences incorporated within these traditions. Next, it compares CDA with other orientations within discourse analysis from the perspective of SFL, and proposes the notion of appliable discourse analysis (ADA). This leads to an overview of the dimensions of ADA, and finally to the question of the place of ADA within a general appliable linguistics.

Key-words: Systemic Functional Linguistics, Appliable Linguistics, Critical Discourse Analysis, Critical Linguistics, Appliable Discourse Analysis.

RESUMO

Este artigo diz respeito à Linguística Sistêmico Funcional (LSF) e Análise Crítica do discurso (ACD) e com a LSF como uma fonte de trabalho acadêmico socialmente justificável. Primeiro localiza a LSF dentro da categoria geral de Linguística aplicável (em oposição tanto a linguística teórica quanto aplicada), uma abordagem ao estudo da linguagem que também é designada como socialmente justificada. Portanto, com base na LSF traça o desenvolvimento primeiro da linguística crítica e depois da ACD, identificando também outras influências características dessas tradições. A seguir, compara a ACD com outras orientações dentro da análise do discurso na perspectiva de LSF, e propõe a noção de análise do discurso aplicável. Isto leva a uma visão geral da dimensão de ADA e finalmente à questão do lugar da ADA dentro de uma linguística geral aplicável.

Palavras-chave: Linguística Sistêmico Funcional, Linguistica Aplicável, Análise Crítica do Discurso, Linguística Crítica , Análise do Discurso Aplicável.

1. SYSTEMIC FUNCTIONAL LINGUISTICS: DEVELOPMENT OF AN APPLIABLE KIND OF LINGUISTICS

Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL; e.g. Hasan, Matthiessen & Webster, 2005, 2007; Halliday & Webster, 2009) grew out of an effort to develop an appliable kind of linguistics, starting with the work by M.A.K. Halliday in the 1950s and drawing on functional and anthropological approaches to language in Europe and North America from the 1920s onwards. Appliable linguistics is a kind of linguistics where theory is designed to have thepotential to be applied to solve problems that arise in communities around the world, involving both reflection and action (see Halliday, 1985, 2002a); it represents a way of relating theory and application as complementary pursuits rather than as a thesis-&-antithesis pair destined to be in constant opposition (and often housed in different university departments): appliable linguistics constitutes the synthesis position bringing theory and application together in dialogue (see Figure 1). Appliable linguistics includes, but extends beyond, appliable discourse analysis(ADA); I will return to this point in the last section of this paper.

Appliable linguistics is also socially accountable linguistics (see Halliday, 1975, 1984a)2 2 . Halliday (1975/ 2003: 89) writes: "Social accountability is a complex notion which cannot be taken in from one angle alone. ... Thereis an ideological component to it, which consists at least in part in eliminatingsomeoftheartificialdisciplinaryboundariesthatwehave inheritedandcontinuedtostrengthen". Social accountability thus includes the kind of transdisciplinarity that he has promoted as a way of creating, disseminating and applying knowledge. . Social accountability has been a central concern in the work by Halliday and his colleagues even before SFL emergedas a distinct theory in the 1960s. In the 1950s, within the Linguistic Group of the British Communist Party, Halliday, Jeffrey Ellis, Dennis Berg, Jean Ure, Trevor Hill, Peter Wexler, and others "worked fairly hard on topics such as the emergence and development of national languages, the status of linguistic minorities, functional variation ('register') in language, unwritten languages and dialects, conceptual-functional grammar, and linguistic typology" (Halliday, 2002b: 118). Social accountability thus includes the notion of a critical stance (as opposed to an uncritical one), but it is much broader: importantly, it also includes programmes for community-oriented action of the kind found in education, healthcare, and other work places. The efforts in the 1950s lead to the gradual development of SFL starting in the early 1960s (see e.g. Matthiessen, 2007, 2010).

To be appliable, an approach to language must be powerful it must empower its practitioners; and power to apply derives from holistic theory and comprehensive descriptions. From the beginning, SFL was designed to be a holistic theory of language in context, with comprehensive descriptions of the systemsof particular languages that could support text analysis (see e.g. Halliday, 1964), the early descriptions being of lexicogrammar (e.g. Halliday, 1967/8; 1969) and of prosodic phonology (e.g. Halliday, 1967)3 3 . While English figured prominently as a focus of descriptive efforts, Halliday and other systemic functional linguists followed J.R. Firth in emphasizing the importance of describing different languages in their own right both "big" languages and "small" ones. Halliday originally worked on Chinese (see Halliday, 2006, for a collection of many of his contributions since the 1950s); and systemic functional linguists have been working on various languages since the 1960s (see e.g. Caffarel, Martin & Matthiessen, 2004). . This holistic approach (cf. Capra, 1996) was, of course, very different from the increasingly dominant purely theoretical work in the traditional "Cartesian" mould by Noam Chomsky and his students and colleagues being exported from the US to various places around the world (together with other US-American commodities in the post-World War II world increasingly dominated by the US).

As the theoretical and descriptive power and potential of SFL continued to grow, researchers were able to address problems in a growing number of areas outside linguistics in the 1960s and the 1970s including education (e.g. Halliday, McIntosh & Strevens, 1964), translation (e.g. Catford, 1965), and computation (e.g. Winograd, 1972; Davey, 1978). This ability to engage with problems that lie outside linguistics itself is in fact related to the different disciplinary currents that have informed and become part of SFL, including anthropology, anthropological linguistics, sociology, educational theory, neuroscience, computational linguistics, and AI. Thus SFL has always been developed in dialogue with other disciplines; it has always been "permeable", as Halliday (1985: 6) puts it: "a salient feature in the evolution of systemic theory: its permeability from outside ... systemic theory has never been walled in by disciplinary boundaries".

Over the years, an increasing number of inter-disciplinary interfaces have been added to SFL. The developments at these different interfaces complement one another. The work in "computational SFL" (e.g. O'Donnell & Bateman, 2005) is less well-known than activities in more exposed areas such as education and healthcare; but it is actually of vital importance to the general project of "appliable linguistics" not only because of computational applications but also, and perhaps more importantly, because the computational work has ensured a degree of explicitness that is often lacking in "discourse analysis" and it has produced computational tools that have extended the analytical power of SFL discourse analysts considerably (see e.g. O'Donnell & Bateman, 2005; Teich, 2009; Wu, 2000, 2009). There are numerous examples that can be cited for example, many researchers have used O'Donnell's UAM tools and Wu's SysConc in research that has a socially accountable orientation. Let me just mention the Scamseek project, which was directed by Jon Patrick at Sydney University, as an example. By leveraging the "computable" potential of SFL, he and his team were able to develop a system that could detect potential electronic scams (delivered by email or available on the web) designed to scam people out of their hard-earned savings (see e.g. Patrick, nd, 2008; Herke, 2003).

In the area of education, Basil Bernstein's sociological theory and research stimulated language-based research into the socialization of children and the transmission of knowledge in relation to social class (e.g. Turner, 1973).Bernstein's (e.g. 1973) theory of codes led to SF work on modelling coding orientation in relation to different groups within a society (e.g. Hasan, 1973, 2004; Halliday, 1994) and to extensive empirical text-based research (e.g. Hasan, 1989). This first round of engagement with Bernstein'swork was followed by a second round, based on his (e.g. 2000) later contributions on discourse, knowledge, pedagogy and (re)contextualization from the 1990s onwards (e.g. Christie & Martin, 2007).

During the 1970s, SFL scholars continued the long-term project of developing a holistic approach to discourse analysis based on comprehensive descriptions of linguistic systems, adding to the discourse-oriented work from the 1960s on lexicogrammar (e.g. Halliday, 1967/8; 1970) and phonology (e.g. Halliday, 1967; Elmenoufy, 1969) by extending the coverage of lexicogrammar to the system of cohesion (e.g. Halliday & Hasan, 1976) and to extra-linguistic level of context, including the contextual staging of text (e.g. Halliday, 1978; Hasan, 1979; 1984). During this period, systemicists also undertook exploratory work on semantics (e.g. Halliday, 1973: Ch. 4; 1984b; Hasan, 1984; Turner, 1987), which was later developed further in the service of discourse analysis (e.g. Martin, 1992). Meanwhile, the description of the grammar continued to be extended, and the first version of Halliday's overview of the grammar (with English as the language of illustration) was ready by the early 1980s (Halliday, 1985). This progress in the development of comprehensive descriptions paved the way for increasingly extensive analyses of discourses in a growing range of institutions, adding significantly to the early work in the 1960s (e.g. Huddleston et al., 1968).

During this period, the 1980s, projects in systemic functional appliable linguistics included a number of institutions that are central to the operations of a society the family (socialization in relation to class and gender: e.g. Hasan, 1989), the work place (e.g. friendship and mateship discussed in Eggins & Slade, 1997), education (e.g. Hasan & Martin, 1989), business and commerce (e.g. Ventola, 1987), verbal art (e.g. Hasan, 1985; Birch & O'Toole, 1987).

These projects depended on the theoretical and descriptive foundation that had been worked outsystematically and with great perseverance since the early 1960s, but they also contributed to the continued development of this foundation. For example, in addressing problems in the institution of education, J.R. Martin, Fran Christie, Joan Rothery and their colleagues and students developed a model of genres in institutions (see e.g. Martin, 1992; Christie & Martin, 1997; Christie & Unsworth, 2005); and in the investigation of literary themes based on the analysis of verbal art, Hasan (e.g. 1985) modelled such themes as higher orders of meaning.

2. SFL AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CRITICAL LINGUISTICS AND CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS

Meanwhile, drawing on SFL as it had developed up through the mid 1970s, Roger Fowler and his colleagues Bob Hodge, Gunther Kress, and Tony Trewlaid the foundations ofCritical Linguistics (CL), starting as a group at the University of East Anglia in the mid 1970s (Fowler et al., 1979) and therefore sometimes referred to as the East Anglia group.They shared key theoretical positions with SFL in general including the views that humans construe their experience through language, that register variation (functional variation) reflects and constructs the division of labour in a society, and that, more generally, "language usage is not merely an effect or reflex of social organization and processes, it is part of social processes" (p. 1); and they used SF descriptions to carry out their analyses of discourses, e.g. drawing on the description of transitivity to reveal patterns in the construal of experience, showing e.g. how journalists can create selective experiential "angles" on events that get reported in the news. Referring to George Orwell's insights into the power of language "Orwellian linguistics"(Hodge & Fowler, 1979), they focussed on the relation between language and social control and between language and ideology.

In their foundational book, Fowler and his colleagues illuminated texts from a range of socially important registers, including regulations, interviews and news reports, through critical analysis, showing for example how bias is introduced into what is presented as supposedly neutral or objective news reports (Trew, 1979). They made other important contributions to the development of CL, including Kress & Hodge (1979, 1988) and Fowler (1991, 1996); see also Steiner (1985) on the theoretical foundation of CL and other contributions to Chilton (1985) on applications to the nuclear arms debate.Later Kress teamed up with Theo van Leeuwen to develop a semiotic description of drawing, painting, photographs and other images (e.g. Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996), thereby pioneering an account that has extended the reach of "critical" approaches to semiotic systems other than language, as shown by Veloso's (2006) multimodal analysis of ideology in comic books produced in the US after 9-11.

The CLproject influenced the development of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) by Norman Fairclough (e.g. 1989, 1992, 1995, 2003, 2005, 2006), though he sees limitations with CL (e.g. 1992: 28-30), and by other scholars, e.g. Ruth Wodak, Carmen Caldas-Coulthard, José Luiz Meurer, and Teun van Dijk (see e.g. Caldas-Coulthard & Coulthard, 1996; Fairclough & Wodak, 1997; Fairclough & Chouliaraki, 1999; van Dijk, 2001; Meurer, 2004; Veloso, 2006). CDA can be characterized as a powerful special-purpose framework (or set of related frameworks) developed "within the tradition of 'critical social science' social science which is motivated by the aim of providing a scientific basis for a critical questioning of social life in moral and political terms, e.g. in terms of social justice and power" (Fairclough, 2003: 15).

CDAcovers a range of approaches; for example,Titscher et al. (2002: 144) distinguish between Fairclough's approach and Ruth Wodak's "discourse-historical method".Fairclough (2005) characterizes CDA as "transdisciplinary"; and Gouveia (2003) presents an analysis giving insight in the nature of CDA in the intellectual context of the development of "new science". Many scholars working within CDA have continued to draw on SF descriptions in their critical analyses of discourses. It also led to further work within SFL, including centrally Martin's (e.g. 1986, 1992: 573ff.) project to give ideology a well-defined location within the SF theory of language in context (and his later work on Positive Discourse Analysis: see below).

Martin (1986: 227)interprets ideology as the highest level of organization within context: ideology > genre > register (in the sense of the contextual parameters of field, tenor and mode). This enables him to explore the distribution of semiotic resources in a society: "one of the things an ideology plane needs to explain is the fact that not everyone in out culture makes use of the same genres" (p. 250).

Let me summarize the developments discussed up to now in a highly schematic diagram, which necessarily leaves out many important details: see Figure 2.

3. SFL AND TYPES OF DISCOURSE ANALYSIS: CDA, PDA

As noted above, there is a historical relationship between SFL and CDA (see Figure 2), and they have remained in an ongoing exchange, as shown by the contributions to e.g. Young & Harrison (2004) and Martin & Wodak (2003), by Veloso (2006), and by Fairclough's (2003: 5-6) comments on the approach to "text analysis" used in CDA. And some key theoretical contributions such as Meurer's (2004) adaptations of Anthony Giddens' (e.g. 1984) structuration theory can be seen as applying equally to SFL and CDA. From the point of view of SFL, CDA is one of a number of specialized, or special-purpose, kinds of discourse analysis; and the "critical" aspect is one of a number of important strands within an appliable and socially accountable kind of discourse analysis, which is in turn located within appliable and socially accountable linguistics (see Section 5).

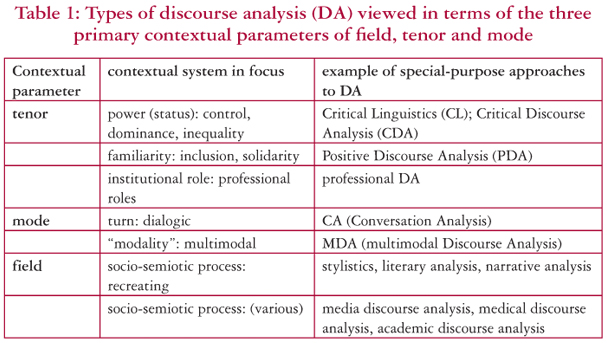

CDA can be characterized alongside other types of discourse analysis in terms of the semiotic environment in which discourses operate4 4 . There are of course many other ways of comparing and contrasting approaches to discourse analysis; for example, Titscher et al. (2000: 51) present a helpful map of different approaches based on disciplinary origins and formative scholars. Here CDA is shown as influenced by Critical Theory (Adorno, Habermas, Horkheimer), Functional Systemic Linguistics (Halliday), Michel Foucault, and (for Wodak's "Discourse Historical Method") Cognitive Linguistics (Shank, Abelson). , i.e. in terms of the three parameters of context identified in SFL (see e.g. Halliday, McIntosh & Strevens, 1964; Halliday, 1978; Martin, 1992; Ghadessy, 1999) field(what is going on in the context, the nature of the activity), tenor(who are taking part in this activity, and the nature of their roles and relationships)and mode(what role is played by language, and by other semiotic systems, in the context): see Table 1.

Among the various specialized forms of discourse analysis, CDA, like CL, is concerned in particular with systems of power within the contextual parameter of tenor. As van Dijk (2001: 353) puts it, "CDA focuses on the ways discourse structures enact, confirm, legitimate, reproduce, or challenge relations of power and dominance in society".

Commenting on this focus on power, Martin (2004) writes: "I do suggest that the main focus of CDA work has been on hegemony on exposing power as it naturalises itself in discourse and thus feeling in some sense part of the struggle against it (something we might naively posit as a trajectory of analysis flowing through Marx, Gramsci and Althusser)", and goes on to argue that it needs to be complemented by a focus on solidarity: "we need a complementary focus on community, taking into account how people get together and make room for themselves in the world in ways that redistribute power without necessarily struggling against it". He proposes to explore this complementary focus through Positive Discourse Analysis (PDA, e.g. Martin, 2002, 2004, 2007, 2008; Martin & Rose, 2003; Vian Jr, 2010).

PDA can involve any stratal features in the analysis of a given text in its context and in terms of the content plane (lexicogrammar and semantics) and context, it can focus on any or all of the different modes of meaning of the metafunctional spectrum; but analysts have given special attention to the interpersonal resources of appraisal (e.g. Martin & White, 2005).(Appraisal analysis is important since the kinds of text being investigated in PDA often also involve issues of affect as part of the tenor parameter of context.) Particular attention has been given to discourses that can serve as positive models for us to followin undertaking constructive socio-semiotic change or at least to learn from, e.g. discourses of reconciliation (e.g. Martin, 2002), of restorative justice (e.g. Martin, Zappavigna& Dwyer, 2009) or more generally of "discourses of hope" (e.g. Gouveia, 2006/7), "discourse which attempts to make the world a better place" (Martin, 2008).

CDA and PDA are both focused on tenor on complementary aspects of human relationships in different institutions, and they may both advocate courses of action based the results of their forms of discourse analysis. Since theyfocus on tenor, they can be said to bespecial-purpose forms of discourse analysis. Other specialized types of discourse analysis focus on other aspects of context other aspects of tenor or systems within either field or mode, as shown in Table 1. These other types could, in principle, also involve a "critical" perspective or a reflexive stance (cf. Candlin, 2002, on professional discourse analysis; his contribution shows that criticality and reflexivity can, in fact, be pursued in parallel with any type of discourse analysis); but since this has not tended to be their main concern, I will not discuss them here5 5 . There has been an extended exchange between CDA and CA researchers: e.g. Fairclough's (1992: 16-20) critical review of CA, and Schegloff's (1997) critical comments on CDA. .

As Table 1 illustrates, scholars have developed various special-purpose forms of discourse analysis over the decades in order to address particular sets of issues. In contrast, systemic functional scholars have consistently striven to develop a general approach to discourse analysis as part of their effort to develop an appliable kind of linguistics. This approach to discourse analysis is what I have called Appliable Discourse Analysis (ADA; see Matthiessen, forthc.). ADA is thus a general purpose approach to discourse analysis but one that is designed to be appliable to a wide range of contexts, including those illustrated in Table 1. For example, in Butt, Lukin & Matthiessen (2004), we undertook a "critical" analysis of a key text used in the fanning of the flames of war, and it was entirely within the scope of systemic functional ADA.

Halliday (2010a) comments on the conditions under which researchers undertake discourse analysis:

An interesting feature of discourse analysis (and one that might serve to distinguish "discourse analysis" from "text analysis", or "text linguistics") is that many of those who undertake discourse analysis approach the task from a particular angle, with a particular attitude towards the text and a view of their own responsibility as analysts. In modern parlance, they have their own agenda.

This may be seen in the choice of the text to be analysed, which is often a text displaying, or seen as displaying, some socio-political stance of which the analyst disapproves: racism, perhaps, or colonialism, or a one-sided attitude to some contemporary or earlier conflict. This has the danger that the analyst might have picked out certain portions of the text which display the features in question without noting how far they are typical of the text as a whole though it might be argued that this does not matter; the fact that they are there at all reveals a possibly unadmitted bias on the part of the writer. What is more problematic is whether the analyst might unwittingly have selected just those features of the lexicogrammar which support them in their argument. This arises if the argument is based on the choice of vocabulary without regard for colligation with the grammar.

Thus in undertaking discourse analysis, analysts must be supported by a framework that enables them to identify and engage with all the dimensions of language in context that are relevant to the task at hand.

4. DIMENSIONS OFDISCOURSE ANALYSIS

One key challenge that socially oriented discourse analysts face is a familiar one in social sciences during the second half of the 20th century (and also of course in natural sciences): to relate the micro-patterns that their analyses reveal the patterns local to a particular (sample of) discourse to the macro-patterns of the culture or society in which the discourses being analysed operate. This is the need for a unitary theory, in Lemke's (1995: 20) terms. Van Dijk (2001: 354) discusses this challenge under the heading of "macro vs. micro":

Language use, discourse, verbal interaction, and communication belong to the micro-level of the social order. Power, dominance, and inequality between social groups are typically terms that belong to a macrolevel of analysis.This means that CDA has to theoretically bridge the well-known "gap" between micro and macro approaches ...

In the developments in mid-20th-century sociology that led to Conversation Analysis (via Garfinkel's, 1967, Ethnomethodology), certain scholars found it essential to focus on local, micro-patterns of everyday interaction and to reject the mainstream taken-for-granted assumptions about macro-categories of social organization (going back to the classic contribution by Sachs, Schegloff & Jefferson, 1974): it was necessary to show empirically that interactants actually orient to particular categories in their conversation instead of taking these categories for granted based on theoretical assumptions6 6 . To empirical linguists concerned with discourse, this important principle would, of course, normally be the obvious starting point for any engagement with text, as is clear from the work by J.R. Firth, Charles C. Fries, M.A.K. Halliday, and the linguists who developed the early corpora in the late 1950s and early 1960s); but the situation was different in sociology, so the principle needed to be spelt out in that disciplinary context. . Here the research programme of CDA is rather different; but even if macro-categories such as power and class are accepted, the challenge still remains of how to relate them to the patterns that emerge in micro-analysis. This is very much one of the concerns in CDA, accentuated by CDA's focus since the 1990s (e.g. Fairclough, 2004b, 2005, 2006; Chouliaraki & Fairclough 1999) on "recent and contemporary processes of social transformation which are variously identified by such terms as "neo-liberalism", "globalisation", "transition", "information society", "knowledge-based economy" and "learning society"" (Fairclough, 2005: 76)7 7 . Chouliaraki & Fairclough (1999: 4) write in relation to theories of "late modernity": "These theories create a space for critical analysis of discourse as a fundamental element in the critical theorisation and analysis of late modernity, but since they are not specifically oriented to language they do not properly fill that space. This is where CDA has a contribution to make." .

To address thechallenge of relating micro-categories to macro-categories, Fairclough (e.g. 1992: 71-73) proposed a "social theory of discourse". This theory involves a "three-dimensional conception of discourse" involving text, discursive practice and social practice, each of which is informed by a distinct analytical tradition (see Figure 3). These traditions are brought together within CDA (p. 72): "the tradition of close textual and linguistic analysis within linguistics" (text), "the macrosociological tradition of analysing social practice in relation to social structure", and "the interpretivist or microsociological tradition of seeing social practice as something which people actively produce and make sense of on the basis of shared commonsense procedures". This general framework has been used extensively in CDA.

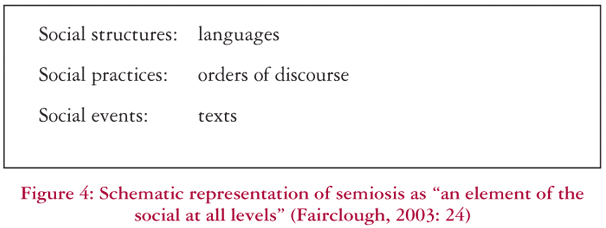

More recently, Fairclough (e.g. 2003, 2004a) has elaborated this account by introducing a global distinction between social and semiotic phenomena and ordering both sets of phenomena from more "abstract" to more "concrete" entities, presenting this schematically as in Figure 4. Fairclough (2003, 2004a) characterizes an order of discourse as "a network of social practices in its language aspect".

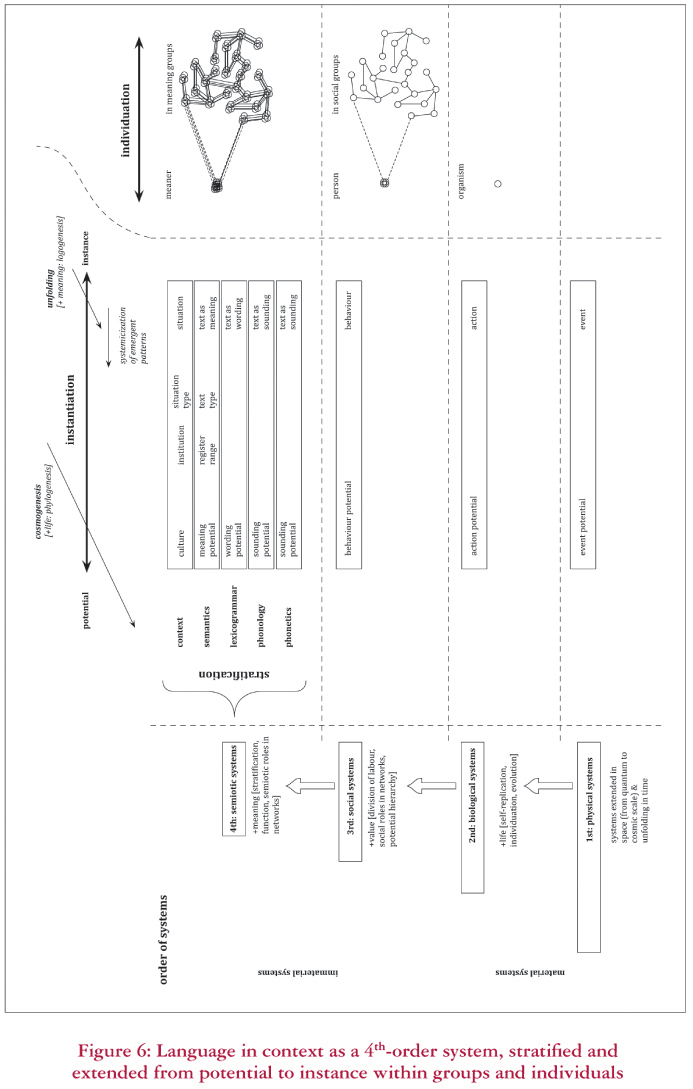

Let me interpret this schematic representation in terms that will link to the dimensions of systemic functional theory presented below: see Figure 5. Here Fairclough's three "levels" are interpreted as phases along the cline of instantiation of systemic functional theory (see Halliday, 1991, Matthiessen, 1993; and further below) and his distinction between social and semiotic phenomena can be interpreted in terms of the ordered typology of systems of SFL (see Halliday, 1996, 2005; Halliday & Matthiessen, 1999, and further below). This interpretation is, of course, a re-interpretation of Fairclough's account; but it serves to highlight certain theoretically interesting issues in the exploration of the relationship between CDA and SFL: the nature of the relationship between social phenomena and semiotic ones8 8 . Fairclough (e.g. 2003) speaks of "semiosis" as "an element of the social at all levels", and "text" is represented as being embedded in "social practice" (see Figure 3). In contrast, in a great deal of work in SFL, semiosis is theorized as being of a higher systemic order than that of social patterning (see below on the ordered typology of systems), and semiotic and social processes are coordinated within context (interpreted as a semiotic construct, as in Halliday, 1978). In other words, semiotic processes are not part of social processes but they organize them and are manifested through them. , and the nature of the distinction between connotative semiotic systems (context) and denotative ones (language and other semiotic systems with their own expression plane; see e.g. Martin, 1992: 493).

While this conceptualization in Fairclough's more recent accounts of CDA brings it closer to SFL in some respects9 9 . However, in other respects, CDA may have moved away from SFL, as in Fairclough's (2003) account of the functions of language. (His account would seem to be oriented towards extrinsic rather than intrinsic functionality, i.e. towards uses of language rather than towards functions as organizing principles of language; see Halliday & Hasan, 1985: Chapter 2; and Martin, 1991). (as interpreted in Figure 5), the general approach to the development of theory taken in SFL has been rather different more akin to approaches associated with general systems theory and its more current successors in the study of complex, adaptive systems. Since SFL isan appliable theory of language in context (and now also of other semiotic systems), it is a general theory rather than a special-purpose one: it is a holistic theory of such systems within a hierarchy of systems of all kinds: see Figure 6; and there has thus been an emphasis on the need to undertake comprehensive (rather than selective) analysis of discourse.Together with other semiotic systems, language is a system of the 4th order of complexity in an ordered hierarchy of systems (e.g. Halliday & Matthiessen, 1999: Ch. 13; Halliday, 1996, 2005; Matthiessen, 2007, 2009):

1st-order systems material systems: physical: systems extending in space (ranging in composition from the quantum world to all of cosmos) and unfolding in time;

2nd-order systems material systems: biological systems: 1st-order systems + life, so self-replicating with individuals and with evolution as the mode of cosmogenesis;

3rd-order systems immaterial systems: social: 2nd-order systems + value, so with individuals as persons serving different social roles in different networks of roles defining social groups and determining division of labour (with the potential for social hierarchy);

4th-order systems immaterial systems: semiotic: 3rd-order systems + meaning, so stratified into a number of semiotic strata and dispersed into different functional strands.

Thus in SFL, discourse analysis can be viewed in terms of this holistic framework. Language and other semiotic systems are seen against the background of systems of all four orders, any one of which may be relevant to critical investigations and programmes for action based on them. This always leaves open the possibility of doing analysis within all four systemic orders (for example in the contexts of neuroscience and medicine); but let me focus on the two immaterial orders of systems:

-

social systems social, anthropological, ethnographic analysis: analysis of discourse as social process (behaviour), and of social processes and systems in their own right using descriptions of social phenomena, e.g. Steiner's (1985, 1991) SF account of social activity (influenced by the activity theory developed by Russian scholars), van Leeuwen's (1996, 2008) work on the representation of social actors and events (e.g. Caldas-Coulthard & van Leeuwen, 2002), Butt's (1991) approach to persons in social role networks; or using ethnographic observation methods (e.g. shadowing people operating in their institutional roles) and interview techniques (e.g. Slade et al., 2008).

-

semiotic systems linguistic analysis (in its broadest sense), multimodal analysis, contextual analysis: prosodic analysis of spoken text (Halliday & Greaves, 2008), lexicogrammatical analysis, including systems from all metafunctions across the rank scale (e.g. Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004), semantic analysis, including all metafunctions (e.g. Eggins & Slade, 1997; Martin & Rose, 2003), contextual analysis, including field, tenor and mode and contextual (generic, schematic) structure (e.g. Ghadessy, 1999); analysis of semiotic systems other than language and multisemiotic analysis (e.g. Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996; Bateman, 2008; Baldry & Thibault, 2006).

The central question of how to relate a text as a micro-domain of patterns to patterns on a larger, macro-scale is thus answered within SFL not by appeal to a single dimension such as text discursive practice social practice, but rather by relating text to other domains that have explicit locations along several, distinct semiotic dimensions (Figure 6):

-

In terms of the hierarchy of composition, texts are made up of sub-texts of (rhetorical) paragraphs of some kind, e.g. of episodes in narratives, of procedures in instructions, of transactions in dialogues; and they may combine to form super-texts, like lessons forming a course of lessons.

-

In terms of the cline of instantiation, texts unfold in time, and a succession of micro-texts unfolding over a period of time may form a macro-text, as when an interpersonal relationship is negotiated through a series of conversations and certain motifs gradually emerge or change (cf. Lam & Webster, 2009); and by the same token, texts that are similar can be distilled into recurrent patterns or text types higher up along the cline of instantiation, and new texts unfold against the background of such text types, confirming patterns or gradually changing them.

-

In terms of the hierarchy of stratification, texts unfold insituations, and situations operate within larger domains, institutions; the semiotic work of an institution is carried out through innumerable situations belonging to different situation types.

-

In terms of the cline of individuation, texts are exchanges between meaners in particular meaning roles; and these meaners are members of larger meaning groups, which in turn are part of the meaning collective of a culture.

-

In terms of the ordered typology of systems, speakers use texts to organize, co-ordinate and negotiate social activitiesof varying extent, e.g. by directing the addressee as s/he is undertaking activities, by advising him/ her to undertake a course of activities, by instructing him/ her in how to undertake a course of activities or by exploring ideas and values.

These dimensions are, in principle, independent of one another; they intersect to form a multi-dimensional semiotic space. For example, we can intersect the cline of instantiation with the hierarchy of immaterial systems (systemic order) and (within semiotic systems) the hierarchy of stratification to form a tabular overview, or an instantiation-stratification matrix (cf. Halliday, 2002c): see Table 2. With the help of this table, we can locate sites of analysis, description and interpretation to be undertaken as part of a particular project of research or application. For examples, it helps us reason about the degree of generality of the claims we want to make. The more general the claims are, the higher up we will have to move along the cline of instantiation; and the higher up we move, the larger our sample of instances has to be thus to make claims about particular institutions, we must compile very extensive corpora of texts in context to ensure empirical validity.

While the dimensions in Table 2are in principle independent of one another, there are, in fact, certain systematicpatterns of association. The cline of instantiation and the cline of individuation are connected (cf. Matthiessen, 2009: 207-208); they represent different perspectives on the move from "micro" to "macro" a system-oriented one and a person-oriented one, respectively. Along the cline of individuation, we can thus trace the connection with regions along the cline, from particular texts arising in the interaction between meaners in particular meaning roles, in particular contexts of situation to the meaning potential residing with the meaning collective. Intermediate between these, we have meaning groups of different sizes whose members share memories of acts of meaning, represented as the subpotentials of meaning that have been distilled from these acts of meaning.

The regions between the outer poles of the clines of instantiation and the cline of individuation are important for the concerns of critical, positive and, more generally, appliable discourse analysis. It is here that we can detect patterns of change emerging from the instantial and individual poles patterns of change of the kind Fairclough and other CDA scholars have focussed on in the last decade to decade and a half like "globalization", the move from "Fordist" to "post-Fordist" workplaces, and also patterns of change of the kind Basil Bernstein identified and articulated, like the shift from position-oriented to person-oriented family structure and the pervasive changes in human history discussed by Halliday (e.g. 1992, 2010b), including the destruction of knowledge and the realignment of patterns within the metafunctions.

Systems of the four different orders have been investigated in terms of a range of different semiotic, social, biological and physical theories. These theories are semiotic constructs (cf. Hjelmslev, 1941; Matthiessen & Nesbitt, 1996; Halliday & Matthiessen, 1999: 30-34), so they are also socially constructed; and in this respect, social and semiotic theories have a special status different from that of biological and physical theories: they are meta-social and meta-semiotic, which is why social and semiotic scholars have been concerned with their positions relative to the systems they study.

CONCLUSION: APPLIABLE LINGUISTICS

As mentioned at the beginning, the concerns that Halliday and his colleagues had in the 1950s led to the development of SFL as one kind of appliable linguistics. The problems that they were concerned with are still with us like problems of power and domination; but these problems are now more pervasive,manifested on a global scale, and other serious problems have emerged(or become more apparent) since the mid 20th century. Among these new challenges is the rapid destruction of our material environment the closing of what James Lovelockhas called "the narrow window of life" on our planet through pollution, deforestation, and other forms of human attack on life.

These problems have been explored in material and social terms; but Halliday (1992) has shown they can also be illuminated in semiotic terms. By focussing on certain key systems deployed in the construalof human experience of the world as meaning, he was able to demonstrate that these systems are still resonant with an earlier agrarian lifestyle when natural resources were inexhaustible but that they are not yet sensitive to the dramatic changes in the human conditionthat have occurred since then. For example, they invite us to construe what are now finite resources as limitless masses, but they make it difficult to construe trees as potent participant in life-sustaining processes. Halliday's account has been very influential, and has stimulated the development of ecolinguistics(e.g. Fill &Mühlhäusler, 2001).The methodology he uses is not that of criticaldiscourse analysis (although it would be possible to build his case along these lines, as his own comments suggest) but rather what we might call criticallanguage description(CLD). That is, he locates his investigation at the potential pole of the cline of instantiation rather than at the instance pole (cf. Figure 6), and critically examines aspects of the meaning potential as it is represented in linguistic descriptions.

CLD and CDA need not, of course, be distinct fields of activity. Just as system and text are not distinct phenomena (as emphasized by Halliday, 1991),but are rather simply the outer poles of the cline of instantiation, potential and instance (cf. Figure 6), so the description of the system and the analysis of texts can and should form a continuum of investigation, as shown diagrammatically in Figure 7. From a critical point of view, it is in fact the region in between the outer poles that is of particular interest. From the point of view of the potential, we can view this intermediate region as variation in the instantiation of the potential dialectal variation, codal variation and registerial variation; and from the point of view of the instance (cf. Halliday, 1994), we can view it as recurrent instantial patterns that we can recognize as instance types.

These perspectives are both needed; they are complementary. If we are interested in tracking changes in society over longer periods of time, then they need to be examined through (successive) descriptions of thesystem, since long-term changes are systemic in nature, both qualitative and quantitative (gradual changes in probabilities). Through successive descriptions of the system, we can reveal changes in the aggregate of varieties that make up a language (or other semiotic system).

Whatever mix of descriptive and analytical techniques we adopt, the region of variationon the cline of instantiation is important because this is where we are likely to find differences between urban centres and rural peripheries, among social classes, genders, age-groups, and professional groups, and among other social distinctions and identities that merit critical investigation (cf. Hasan, 2004).

CLD and CDA are both aspects of appliable linguistics, just as PDA, professional discourse analysis and other specialized forms of discourse analysis are (see Figure 7); and the critical stance is one possible manifestation of social accountability. However, there are many projects of great importance that lie outside the sphere of CDA but which still relate centrally to activities in linguistics informed by social accountability. Let me give just two examples from very different areas of concern.

-

There is an urgent need for more descriptive projectsto produce accounts of languages that are endangered in communities that are on the fringes of modern nation states, so that it is possible to develop educational materials and other community resources to improve the chances of survival and sustainability and to preserve the semiotic heritage embodied in such languages (for general discussions, see e.g. Harrison, 2007; Evans, 2010; for particular examples based on SFL, see e.g. Akerejola, 2005; Kumar, 2009) world views (including ethnoscience) and modes of interaction as part of our semo-diversity.There is now increasing awareness of the importance of such descriptive projects devoted to language description, conservation and revitalization, with a growing number of organizations and publications supporting these efforts (see e.g. Grenoble & Whaley, 2006). Work in this area is, of course, dependent on language policy and on approaches to curriculum design in education; so it has to be part of a broad-based programme grounded in the decisions and plans by members of the community10 10 . Using SFL and the PDA orientation within it, Gouveia (2006/7) sheds light on how the "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment" works as "a discourse of hope", "a discourse with an empowering attitude". Understanding how such discourses work in the area of language policy and education is an important part of the development of broad-based programmes supporting or revitalizing endangered communities. .

-

Designed human systemsoften involve of two or more systemic orders some combination of semiotic, social, biological and physical systems (cf. Figure 6), and they are becoming increasingly complex: power plants, air traffic control systems and other forms of mass communication, the internet, healthcare systems, and so on. These systems must be robust and fault tolerant, but they are subject to the risk of failure. Failures may occur within any of the systemic orders equipment may become faulty (physical failure), operators may be distracted or incapacitated (biological failure), and organizational procedures may not work (social failure). These modes of failure are all generally recognized, but perhaps the most pervasive kind of failure is semiotic failure: designed human systems fail because the flow of information that they rely on is disrupted in one way or another and there is not enough semiotic fault tolerance built into them. For example, in a study of emergency departments in large hospitals, Slade et al. (2008) identify moments of semiotic (or "communicative") risk in the course of a patient's journey through such a department. Once such potential semiotic failures have been identified, it is possible to boost the semiotic robustness of the system in the case emergency departments, this might involve check lists and systems of electronic patient records.

Work in both these areas can have significant impact on the human condition, or even on the planetary condition since human activities have now reached a stage where they have global impact across the different orders of system. In addition to these two areas, there are many others, including education if we are to address and overcome the problems identified by research in CDA, we need to build solutions into institutions of education; and translation if we are to deal with all the challenges (and opportunities) we face in an increasingly globalized world, we need to address and overcome the problems of understanding and respect that exist between communities; and these solutions will involve translator and interpreter training.

Whether we are concerned with appliable approaches in general or critical or positive ones in particular, we need to include both reflection and action in our paradigm; Halliday (1995: 11) emphasizes that SFL "is explicitly constructed both for thinking with and for acting with". There are now many examples in different areas of how SF programmes of action have been developed based on the results of analysis and description, including syllabus and curriculum design and other aspects of pedagogy based on the analysis of texts used in schools, training materials for work places based on the analysis of work-place texts, health information for patients based on the analysis of medical consultations, and natural language processing systems based on descriptions of languages.

Recebido em novembro de 2011

Aprovado em dezembro de 2011

E-mail: cmatthie@me.com

- AKEREJOLA, Ernest. 2005. A systemic functional grammar of Òkó. Macquarie University: Ph.D. thesis.

- BALDRY, Anthony & Paul J. THIBAULT. 2006. Multimodal transcription and text analysis: a multimedia toolkit and coursebook. London & Oakville: Equinox.

- BATEMAN, John A. 2008. Multimodality and genre: a foundation for the systematic analysis of multimodal documents. London & New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- BERNSTEIN, Basil (ed.). 1973. Class, codes and control.Volumes 1& 2. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ______. 1977. Class, codes and control.Volume 3. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ______. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique 2nd edition. London: Rowan and Littlefield.

- BIRCH, David & Michael O'TOOLE (eds.). 1988. Functions of style.London: Frances Pinter.

- BUTT, David G. 1991. "Some basic tools in a linguistic approach to personality: a Firthian concept of social process." In Fran Christie (ed.), Literacy in social processes: papers from the Inaugural Australian Systemic Functional Linguistics Conference, Deakin University, January 1990. Darwin: Centre for Studies of Language in Education, Northern Territory University. 23-44.

- BUTT, David G., Annabelle LUKIN & Christian M.I.M. MATTHIESSEN. 2004. "GrammarThe First Covert Operation of War." Discourse & Society 15(2-3): 267-290.

- CAFFAREL, Alice, J.R. MARTIN & Christian M.I.M. MATTHIESSEN (eds.). 2004. Language typology: a functional perspective. (Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 253.) Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- CALDAS-COULTHARD, Carmen Rosa & Malcolm COULTHARD (eds.). 1996. Text and practices: readings in Critical Discourse Analysis London: Routledge.

- CALDAS-COULTHARD, Carmen Rosa and Theo VAN LEEUWEN 2002. "4. Stunning, shimmering, iridescent: toys as the representation of gendered social actors." In Lia Litosseliti & Jane Sunderland (eds.), Gender identity and discourse analysis.Amsterdam: John Benjamins.91108.

- CAPRA, Fritjof. 1996. The web of life. New York: Doubleday.

- CHILTON, Paul (ed.). 1985.Language and the nuclear arms debate: nukespeak today. London: Pinter.

- CHRISTOPHER N. Candlin (ed.). 2002. Research and Practice in Professional Discourse Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press.

- CATFORD, J.C. 1965. A linguistic theory of translation. London: Oxford University Press.

- CHRISTIE, Frances & J.R. MARTIN (eds.). 1997. Genre and institutions: social processes in the workplace and school. London: Cassell.

- ______. 2007. Language, knowledge and pedagogy: functional linguistic and sociological perspectives. London & New York: Continuum.

- CHRISTIE, Frances & Len UNSWORTH. 2005. "Developing dimensions of an educational linguistics." In Hasan, Matthiessen & Webster (eds.), Volume 1. 217-250.

- CHOULIARAKI, Lilie & Norman FAIRCLOUGH. 1999. Discourse in late modernity: rethinking Critical Discourse Analysis. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- DAVEY, Anthony. 1978. Discourse production: a computer model of some aspects of a speaker. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- EGGINS, Suzanne & Diana SLADE. 1997. Analysing casual conversation. London: Cassell.

- ELMENOUFY, Afaf. 1969. A study of the role of intonation in the grammar of English. University of London: Ph.D. thesis.

- EVANS, Nicholas. 2010. Dying words: endangered languages and what they have to tell us. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- FAIRCLOUGH, Norman. 1989. Language and power London: Longman.

- ______. 1992. Discourse and social change Cambridge: Polity.

- ______. 1995. Critical Discourse Analysis: the critical study of language. London: Longman.

- ______. 2003. Analysing discourse: textual analysis for social research London: Routledge.

- ______. 2004a. "Semiotic aspects of social transformation and learning." In Rebecca Rogers (ed.) New Directions in Critical Discourse Analysis: Semiotic Aspects of Social Transformation and Learning.Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. 225-235.

- ______. 2004b. "Critical Discourse Analysis in researching language in the New Capitalism: overdetermination, transdiscliplinarity, and textual analysis." In Young & Harrison (eds.). 103-122.

- ______. 2005. "Critical Discourse Analysis." Marges Linguistiques 9: 76-94.

- ______. 2006. Language and globalization London: Routledge.

- FAIRCLOUGH, Norman L. & Ruth WODAK. 1997. "Critical discourse analysis." In Teun A. van Dijk (ed.), Discourse studies: amultidisciplinary introduction, Vol. 2. discourse as social interaction. London: Sage. 258-284.

- FILL, Alwin & Peter MÜHLHÄUSLER. 2001. The ecolinguistics reader. London: Continuum.

- FOWLER, Roger. 1991. Language in the news: discourse and ideology in the press. London: Routledge.

- ______. 1996. Linguistic criticism. Second edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- FOWLER, Roger, Bob HODGE, Gunther Kress & Tony TREW. 1979. Language and control. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- GARFINKEL, Harold. 1967. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- GHADESSY, Mohsen (ed.). 1999. Text and context in functional linguistics. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- GIDDENS, Anthony. 1984. The constitution of society outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- GOUVEIA, Carlos A.M. 2003. "Critical Discourse Analysis and the development of New Science." In Gilbert Weiss & Ruth Wodak (eds.),Critical Discourse Analysis: theory and interdisciplinarity. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 47-62.

- ______. 2006/7. "The role of a Common European Framework in the elaboration of national language curricula and syllabuses." Cadernos de Linguagem e Sociedade (Papers on Language and Society) 8: 8-25.

- GRENOBLE, Lenore A. & Lindsay J. WHALEY. 2006. Saving languages: an introduction to language revitalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- HALLIDAY, M.A.K. 1964. "Syntax and the consumer." In C.I.J.M. Stuart (ed.), Report of the Fifteenth Annual (First International) Round Table Meeting on Linguistics and Language. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. 11-24. Reprinted in Halliday, M.A.K. 2003. On Language and Linguistics. Volume 3 of Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday. Edited by Jonathan Webster. London & New York: Continuum. Chapter 1: 36-49.

- ______. 1967. Intonation and Grammar in British English. The Hague: Mouton. (Janua Linguarum Series Practica 48)

- ______. 1967/8. "Notes on transitivity and theme in English 1-3."Journal of Linguistics 3.1: 37-81, 3.2: 199-244, 4.2: 179-215.Reprinted in Halliday, M.A.K. 2005. Studies in English Language. Volume 7 in the Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday, edited by Jonathan Webster. London & New York: Continuum. Chapter 1: 5-54.Chapter 2: 55-109. Chapter 3: 110-153.

- ______. 1969. "Options and functions in the English clause."Brno Studies in English 8: 81-8. Reprinted in Halliday, M.A.K. 2005. Studies in English Language. Volume 7 in the Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday, edited by Jonathan Webster. London & New York: Continuum. Chapter 4: 154-163.

- ______. 1970. "Functional diversity in language, as seen from a consideration of modality and mood in English."Foundations of Language 6: 322-361. Reprinted in Halliday, M.A.K. 2005. Studies in English Language. Volume 7 in the Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday, edited by Jonathan Webster. London & New York: Continuum. Chapter 5: 164-204.

- ______. 1973. Explorations in the Functions of Language. London: Edward Arnold.

- ______. 1975. "The context of linguistics." In FrancisP.Dinneen (ed.), Report of the Twenty-fifth Annual Round Table Meeting on Linguistics and Language Study (MonographSeriesinLanguagesand Linguistics17). Washington, D.C.: GeorgetownUniversityPress. Reprinted in Halliday, M.A.K. 2003. On Language and Linguistics. Volume 3 of Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday. Edited by Jonathan Webster. London & New York: Continuum. 74-91.

- ______. 1978. Language as social semiotic: the social interpretation of language and meaning. London & Baltimore: Edward Arnold & University Park Press.

- ______. 1984a. "Linguistics in the university: the question of social accountability." In James E. Copeland (ed.), New directions in linguistics and semiotics. Houston, Texas: Rice University Studies. 51-67.

- ______. 1984b. Language as code and language as behaviour: a systemic-functional interpretation of the nature and ontogenesis of dialogue.

- M.A.K. Halliday Robin P. Fawcett, Sydney Lamb & Adam Makkai (ed.), The semiotics of language and culture. London: Frances Pinter. Volume 1: 3-35. Reprinted in Halliday, M.A.K. 2003. On Language and Linguistics. Volume 3 of Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday. Edited by Jonathan Webster. London & New York: Continuum. Chapter 10: 226-250.

- ______. 1985. "Systemic background." In James D. Benson & William S. Greaves (eds.), Systemic perspectives on discourse. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex. 1-15.

- ______. 1991. "The notion of 'context' in language education."In Thao Le & Mike McCausland (eds.), Interaction and development: proceedings of the international conference, Vietnam, 30 March - 1 April 1991. University of Tasmania: Language Education. 1-26. Reprinted in M.A.K. Halliday (2007), Language and education. Volume 9 in the Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday, edited by Jonathan Webster. London & New York: Continuum. 269-290.

- ______. 1992. "New ways of meaning: a challenge to applied linguistics."Greek Applied Linguistics Association, Journal of Applied Linguistics 6.

- ______. 1994. "Language and the theory of codes." In Alan Sadovnik (ed.), Knowledge and pedagogy: the sociology of Basil Bernstein. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex. 124-142.

- ______. 1996. "On grammar and grammatics." In Ruqaiya Hasan, Carmel Cloran & David Butt (eds.), Functional descriptions: theory into practice. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 1-38. Reprinted in Halliday, M.A.K. 2002.

- On grammar. Volume 1 of Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday. Edited by Jonathan Webster. London & New York: Continuum. Chapter 15: 384-417.

- ______. 2002a. "Applied linguistics as an evolving theme." Presented at AILA 2002, Singapore. Published in M.A.K. Halliday (2007), Language and education. Volume 9 of the Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday, edited by Jonathan Webster. London & New York: Continuum. 1-19.

- ______. 2002b. "M.A.K. Halliday." In Keith Brown & Vivien Law (eds.), Linguistics in Britain: personal histories. (Publications of the Philological Society.) Oxford: Blackwell. 116-126.

- ______. 2002. "Computing meanings: some reflections on past experience and present prospects." In Guowen Huang & Zongyan Wang (eds.),Discourse and Language Functions. Shanghai: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. 3-25. Reprinted in M.A.K. Halliday (2005), Computational and quantitative studies. Volume 6 in the Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday, edited by Jonathan Webster. London & New York: Continuum. 239-267.

- ______. 2005. "On matter and meaning: the two realms of human experience."Linguistics and the Human Sciences 1.1: 59-82.

- ______. 2006. Studies in Chinese Language.Volume 8 of the Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday, edited by Jonathan J. Webster. London & New York: Continuum.

- ______. 2010a."Text, discourse and information: a systemic-functional overview." Written version of plenary talk presented the biannual conference on Discourse Analysis, Tongji University, Shanghai, November 2010.

- ______. 2010b. "Language evolving: some systemic functional reflections on the history of meaning." Written version of plenary talk at ISFC 2010 at the University of British Columbia.

- HALLIDAY, M.A.K. & William S. GREAVES. 2008. Intonation in the grammar of English. London: Equinox.

- HALLIDAY, M.A.K. & Ruqaiya HASAN. 1985. Language, context and text: a social semiotic perspective. Geelong, Vic.: Deakin University Press.

- HALLIDAY, M.A.K., Angus MCINTOSH & Peter STREVENS. 1964. The linguistic sciences and language teaching. London: Longman.

- HALLIDAY, M.A.K. & Christian M.I.M. MATTHIESSEN. 1999. Construing experience through meaning: a language-based approach to cognition. London: Cassell.

- ______. 2004. An introduction to functional grammar. Third Edition. London: Arnold.

- HALLIDAY, M.A.K. & Jonathan WEBSTER (eds.). 2009.Continuum companion to systemic functional linguistics. London & New York: Continuum.

- HARRISON, David. 2007. When languages die: the extinction of the world's languages and the erosion of human knowledge. Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.

- HASAN, Ruqaiya. 1973. "Code, register and social dialect." In Basil Bernstein (ed.), Class, Codes and Control: applied studies towards a sociology of language. Volume 2. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 253-292.

- ______. 1979. "On the notion of text." In Janos Petöfi (ed.), Text versus sentence: basic questions of text linguistics. Papers in Text Linguistics 20. Hamburg: Buske.369-390.

- ______. 1984. "The nursery tale as a genre."Nottingham Linguistic Circular 13. [Reprinted in Ruqaiya Hasan (1996), Ways of saying: ways of meaning: selected papers of Ruqaiya Hasan. Edited by Cloran, Carmel, David Butt & Geoffrey Williams. London: Cassell. 51-72.

- ______. 1985. Linguistics, language and verbal art. Geelong, Vic.: Deakin University Press.

- ______. 1989. "Semantic variation and sociolinguistics."Australian Journal of Linguistics 9: 221-275.

- ______. 2004. "Analysing discursive variation." In Young & Harrison (eds.). 15-52.

- HASAN, Ruqaiya & James R. MARTIN (eds.). 1989. Language development: learning language, learning culture. Meaning and choice in language. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex.

- HASAN, Ruqaiya, Christian M.I.M. MATTHIESSEN & Jonathan WEBSTER (eds.). 2005, 2007. (Continuing Discourse on Language: A Functional Perspective, Volume 1 (2005) and Volume 2 (2007). London: Equinox Publishing.

- HERKE, Maria. 2003. "Arresting the Scams: Using Systemic Functional Theory to Solve a Hi-Tech Social Problem."CIEFL Bulletin Special Issue 102-119.

- HJELMSLEV, Louis. 1943. Omkring sprogteoriens grundlæggelse. København: Akademisk Forlag. (English version. 1961 Prolegomena to a Theory of Language. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

- HODGE, Bob & Roger FOWLER. 1979. "Orwellian linguistics." In Fowler et al., 6-25.

- HUDDLESTON, Rodney D., Richard A. HUDSON, Eugene WINTER & A. HENRICI. 1968. Sentence and clause in Scientific English: final report of O.S.T.I. Programme. University College London: Communication Research Centre.

- KRESS, Gunther R. & Robert HODGE. 1979. Language as ideology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ______. 1988. Social semiotics. London: Polity.

- KRESS, Gunther & Theo VAN LEEUWEN. 1996. Reading images: the grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

- KUMAR, Abhishek. 2009. A systemic functional description of the grammar of Bajjika Macquarie University: Ph.D. thesis.

- LAM, Marvin & Jonathan WEBSTER. 2009. "The lexicogrammatical reflection of interpersonal relationship in conversation." Discourse Studies 11(1): 37-57.

- LEMKE, Jay L. 1995. Textual Politics: discourse and social dynamics. London & Bristol, PA: Taylor & Francis.

- MARTIN, J.R. 1986. "Grammaticalizing ecology: the politics of baby seals and kangaroos." In Elizabeth A. Grosz, Terry Threadgold & M.A.K. Halliday (eds.), Semiotics - Ideology - Language.Sydney: Sydney Association for Studies in Society and Culture. 225-267.

- ______. 1991. "Intrinsic functionality: implications for contextual theory."Social Semiotics 1(1): 99-162.

- ______. 1992. English Text: system and structure. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- ______. 2002. "Blessed are the peacemakers: reconciliation and evaluation". In Candlin (ed.), 187-227.

- ______. 2004. "Positive discourse analysis: power, solidarity and change." Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses49:179-200.

- ______. 2007. "English for peace: towards a framework of Peace Sociolinguistics: response."World Englishes 26(1): 83-85.

- ______. 2008. "Intermodal reconciliation: mates in arms." In Len Unsworth (ed.), New literacies and the English curriculum: multimodal perspectives London: Continuum. 112- 148.

- MARTIN, J.R. & David ROSE. 2003. Working with discourse: meaning beyond the clause. London & New York: Continuum.

- MARTIN, J.R. & Peter R.R. WHITE. 2005. The Language of Evaluation: Appraisal in English London & New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- MARTIN, J.R. & Ruth WODAK (eds.). 2003. Re/Reading the Past: Critical and Functional Perspectives on Time and Value (Discourse Approaches to Politics, Society and Culture, 8.) Amsterdam & Philadelphia: Benjamins.

- MARTIN , J.R., Michelle ZAPPAVIGNA , Paul G. DWYER. 2009. "Negotiating narrative: story structure and identity in youth justice conferencing."Linguistics and the Human Sciences 3(2): 221-253.

- MATTHIESSEN, Christian M.I.M. 1993. "Register in the round: diversity in a unified theory of register analysis." In Mohsen Ghadessy (ed.), Register analysis: theory and practice. London: Pinter. 221-292.

- ______. 2007. "The "architecture" of language according to systemic functional theory: developments since the 1970s." In Ruqaiya Hasan, Christian M.I.M. Matthiessen & Jonathan Webster (eds.), Continuing discourse on language Volume 2. London: Equinox. 505-561.

- ______. 2009. "Meaning in the making: meaning potential emerging from acts of meaning." In Anniversary Issue of Language Learning 59 (Supplement 1): 211-235.

- ______. 2010. "Systemic Functional Linguistics Developing." Annual Review of Functional Linguistics 2: 8-63.

- Matthiessen, Christian M.I.M. forthc. "Appliable Discourse Analysis." Developing Systemic Functional Linguistics, edited by Fang Yan & Jonathan J. Webster. London: Continuum.

- MATTHIESSEN, Christian M.I.M. & Christopher NESBITT. 1996. "On the idea of theory-neutral descriptions." In Ruqaiya Hasan, Carmel Cloran & David Butt (eds.), Functional descriptions: theory in practice. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 39-85.

- MEURER, José Luiz. 2004. "Role prescriptions, social practices, and social structures: a sociological basis for the contextualization of analysis in SFL and CDA." In Young & Harrison (eds.). 85-99.

- O'DONNELL, Michael & John A. BATEMAN. 2005. "SFL in Computational Contexts. " In Ruqaiya Hasan, Christian M.I.M. Matthiessen & Jonathan Webster (Eds.), Continuing Discourse on Language A Functional Perspective, Volume 1. London: Equinox Publishing. 343-382.

- PATRICK, Jon. nd. "The Scamseek Project text mining for financial scams on the Internet." Available at: http://sydney.edu.au/engineering/ it/~lkmrl/Scamseek-Project-data-mining-conf-v0.pdf

- PATRICK, Jon. 2008. "The Scamseek Project using Systemic Functional Grammar for text categorization." In Jonathan J. Webster (ed.), Meaning in context: implementing intelligent applications of language studies. London & New York: Continuum. 221-233.

- SACKS, Harvey, Emanuel A. SCHEGLOFF & Gail JEFFERSON. 1974. "A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation."Language50: 696-735.

- SCHEGLOFF, Emanuel A. 1997. "Whose Text? Whose Context?" Discourse & Society 8(2): 165-187.

- SCHIFFRIN, Deborah, Deborah TANNEN & Heidi E. HAMILTON (eds.). 2001. The handbook of discourse analysis. Oxford: Blackwell.

- SLADE, Diana, Hermine SCHEERES, Marie MANIDIS, Christian M.I.M. MATTHIESSEN, Rick IEDEMA, Maria HERKE, Jeannette MCGREGOR, Roger DUNSTON & Jane STEIN-PARBURY. 2008. "Emergency Communication: The discursive challenges facing emergency clinicians and patients in hospital emergency departments." Discourse & Communication 2(3): 289-316.

- STEINER, Erich. 1985. "The concept of context and the theory of action." In Chilton (ed.). 215-230.

- ______. 1991. A functional perspective on language, action and interpretation. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- TEICH, Elke. 2009. "Linguistic computing." In Halliday & Webster (eds.).113-127.

- TITSCHER, Stefan, Michael MEYER, Ruth WODAK & Eva VETTER. 2000. Methods of text and discourse analysis. London: Sage.

- TREW, Tony. 1979. "Theory and ideology at work." In Fowler et al., 94-116.

- TURNER, Geoffrey J. 1973. "Social class and children's language of control at age five and age 7." In Basil Bernstein (ed.), Class, Codes and Control II: applied studies towards a sociology of language. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 135-201.

- ______. 1987. "Sociosemantic networks and discourse structure." In M.A.K. Halliday & Robin P. Fawcett (eds.), New developments in Systemic Linguistics. London: Frances Pinter. 64-93.

- VAN DIJK, Teun. 2001. "Critical Discourse Analysis." In Schiffrin, Tannen & Hamilton (eds.). 352-371.

- VAN LEEUWEN, Theo. 1996. "The representation of social actors." In Caldas-Coulthard, Carmen Rosa & Malcolm Coulthard (eds.). Text and Practices: Readings in Critical Discourse Analysis London: Routledge. 32-70.

- ______. 2008. Discourse and practice: new tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. (Oxford studies in sociolinguistics.) Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- VELOSO, Francisco O. D. 2006. "Never awake a sleeping giant...": a multimodal analysis of post 9-11 comic books Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina: Ph.D. thesis.

- VENTOLA, Eija. 1987. The structure of social interaction: a systemic approach to the semiotics of service encounters. London: Frances Pinter.

- VIAN JR, Orlando. 2010. "Gêneros do discurso, narrativas e avaliação nas mudanças sociais: a análise de discurso positiva." Cadernos de Linguagem e Sociedade 11 (2): 78-96.

- WINOGRAD, Terry. 1972. Understanding Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- WU, Canzhong. 2000. Modelling linguistic resources. Macquarie University: Ph.D. thesis.

- ______. 2009. "Corpus-based research." In Halliday & Webster (eds.). 128-142.

- YOUNG, Lynne & Claire HARRISON (eds.). 2004. Systemic functional linguistics and critical discourse analysis: studies in social change. London & New York: Continuum.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

20 May 2013 -

Date of issue

2012

History

-

Received

Nov 2011 -

Accepted

Dec 2011