ABSTRACT

In this article, I analyse how practices referred to generically in the historical documentation as ‘batuque’ (drums) underwent a process of homogenization and scrutinization by diverse Portuguese colonial agents. On one hand, the colonial agents insisted on unifying everything they saw as dance and music under the generic category of ‘batuque.’ On the other hand, the need for a better understanding of the subordinate Africans ended up producing colonial responses that shifted between a dissection of the term in search of a more accurate apprehension of what was being observed and an incorporation of these practices into the colonial enterprise. This process was conceived by the colonial agents as a way of appropriating the dances, songs and music made by the natives of southern Mozambique into the ultramarine Portuguese nationalist discourse.

Keywords:

colonialism; homogenization; ‘batuques’; Southern Mozambique

RESUMO

No artigo analiso como as práticas designadas genericamente como batuques passaram por um processo de homogeneização e de escrutinização por parte de diferentes agentes da ação colonial portuguesa. Por um lado, insistiu-se em unificar danças e músicas na categoria genérica de batuque; por outro, a necessidade de compreender os povos dominados acabou por produzir respostas coloniais que transitaram entre um destrinchar desse termo em busca de uma apuração mais fidedigna daquilo que se presenciava e uma incorporação dessas práticas na empresa colonial. Ao mesmo tempo, promoveu-se uma incorporação dessas práticas na empresa colonial. Esse processo foi concebido pelos agentes coloniais portugueses como forma de apropriação dessas danças, canções e músicas feitas pelos nativos do sul de Moçambique para positivação de um discurso nacionalista português.

Palavras-chave:

colonialismo; homogeneização; “batuques”; sul de Moçambique

The policies of the Portuguese colonial enterprise in southern Mozambique, initiated especially after the defeat of the Gaza Kingdom in the 1890s, produced intense migratory pressures on the native African populations with the aim of incorporating them into the labour market and the mechanisms of exploitation created by the colonial regime. As a consequence, there was an intense migration to the urban spaces of the colonial capital, the city of Lourenço Marques, present-day Maputo, and to the mines of South Africa. According to the Centro de Estudos Africanos of the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, in 1904 miners of Mozambican origin corresponded to 60.2% of the mine labour force, rising to 65.4% in 1906 (Centro de Estudos Africanos, 1998CENTRO de Estudos Africanos, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane. O mineiro moçambicano: um estudo sobre a exportação de mão de obra em Inhambane. [1977]. Maputo: Centro de Estudos Africanos, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, 1998., p. 35). Researchers who have focused on analysing the labour relations implemented by Portuguese colonialism in southern Mozambique argue that from the beginning of the twentieth century a system took shape that involved the migration of Mozambican workers to supply sectors requiring labour in the city of Lourenço Marques, but above all to meet the high demand for manual labourers in the South African mines (Harries, 1994HARRIES, Patrick. Work, Culture, and Identity: Migrant Laborers in Mozambique and Souht Africa, c. 1860-1910. Portsmouth: Heinemann; Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press; London: James Currey, 1994.; Penvenne, 1995PENVENNE, Jeanne Marie. African Workers and Colonial Racism: Mozambican Strategies and Struggles in Lourenço Marques, 1877-1962. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 1995.; Penvenne, 2015PENVENNE, Jeanne Marie. Women, Migration & the Cashew Economy in Southern Mozambique: 1945-1975. Oxford: James Currey, 2015.).

Among other effects, the attempt to resolve the problems faced by Portugal in its attempts to compel native populations to join the labour market, incorporating them into a monetary economic system, led to the formulation of legislation that divided the population of the colonial world into specific categories. These laws, based on region of origin and racial categorizations, legally defined the demographic groupings that comprised the populations living in Portugal’s African colonies. This set of legal provisions, formulated between the end of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth, juridically established the existence of two categories that would formally define the place of black/African populations within the frameworks of Portuguese colonialism until the 1960s: the assimilated (“assimilados”) and the indigenous (“indígenas”). Assimilated peoples were described in diverse codes implemented under colonial rule as Africans who had abandoned the “uses and customs of their race,” adopting the habits of the so-called civilized world. Indigenous peoples, who made up the vast majority of the population, were Africans who continued to practice and live on the basis of the “uses and customs of their race.” The idea of defining the indigenous person as someone disinclined to work and, consequently, naturally idle was closely associated with the production of laws that conceived work as a civilizing instrument (Zamparoni, 2007ZAMPARONI, Valdemir. De escravo a cozinheiro: colonialismo & racismo em Moçambique. Salvador: EDUFBA/Ceao, 2007.).

Establishing the moral obligation to work for those people defined as indigenous - enforced through the Indigenous Labour Code of 1899, followed by similar legislation in 1906, 1911, 1914, 1926 and 1928, and the Political, Civil and Criminal Statute of the Indigenous Peoples of Guinea, Angola and Mozambique, decreed in 1929 - had the ultimate aim of enabling the emergence of a subproletarian and underpaid black labour force, primarily characterized by its abundance, low cost and discipline. Generally speaking, the construction of mechanisms designed to push Africans, especially indigenous peoples, into the capitalist labour market that had developed with the advent of colonialism, whether through forced labour or through the voluntary sale of their labour force, ran in parallel with the production of this indigenous category itself and its supposed sociocultural characteristics. One of the justifications of the Portuguese colonization in Africa was constructed precisely on the basis of legislative measures that attempted to regulate the productivity of native workers with an idea of dignified work capable of guiding this population towards civilization (Jerónimo, 2009JERÓNIMO, Miguel Bandeira. Livros brancos, almas negras: a “Missão Civilizadora” do colonialismo português (c.1870-1930). Lisboa: ICS (Imprensa de Ciências Sociais), 2009.).

In general, the bibliography on the construction of this Portuguese colonial juridical-governmental framework, as well as the investigations into the dynamics established between its colonizing practices and the diverse sociocultural logics of African native populations, has interpreted the contacts on the basis of a paradox in the European colonial project. As Patrícia Ferraz de Matos explains, in the colonial paradox “it was argued that the ‘uses and customs’ of the natives needed to be protected; on the other hand, it was also argued that the natives had to be guided towards a process of assimilation (in which some of these ‘uses’ would naturally vanish)” (Matos, 2006MATOS, Patrícia Ferraz de. As Côres do Império: representações raciais no Império Colonial Português. Lisboa: ICS (Imprensa de Ciências Sociais), 2006., p. 253).2 2 Along these lines, see MACAGNO, 2001; COOPER, 2005.

The construction of the idea of popular culture - with specific ‘uses and customs’ requiring classification and comprising a folklore that, in turn, symbolized the cultural amalgam of a specific people and thus of a unified nation, promoting the homogenization and standardization of diverse cultural practices - is a recurrent phenomenon observable in various parts of the world from the second half of the nineteenth century. In the case of Portugal, works like those by Vera Marques Alves - concerning the work of the Secretariado da Propaganda Nacional and the nationalist uses made of popular culture by the social sciences (Alves, 2013ALVES, Vera Marques. Arte popular e nação no Estado Novo: a política folclorista do Secretariado de Propaganda Nacional. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, 2013.) - and by Marcos Cardão - concerning the relations between nationalist-colonialist political ideological projects and what the author calls ‘mass culture’ (Cardão, 2014CARDÃO, Marcos. Fado tropical: o luso-tropicalismo na cultura de massas (1960-1974). Lisboa: Ed. Unipop, 2014.) - demonstrate how the Portuguese New State (1933-1974) strove to develop projects to homogenize cultural practices, funnelling them into the pigeonhole of folklore and directing them towards a specific political-ideological aim.

In the case of the populations of southern Mozambique, the views prevailing in Portuguese metropolitan circles concerning the relations that needed to be established with the colonized native populations, during the period analysed, underwent a process of classification that situated natives within a social and cultural order that had to be paradoxically conserved and combatted simultaneously. As a result of this method, the imprisoning of these classified Africans in a form of being that took them to be immutable consequently limited them - at least in the analytic endeavour of the men of Empire - to a particular destiny (Pereira; Nascimento, 2017PEREIRA, Matheus Serva; NASCIMENTO, Washington Santos. Etnicidades e os Outros em contextos coloniais africanos: reflexões sobre as encruzilhadas entre História e Antropologia. In: SANTANA, Marise de; FERREIRA, Edson Dias; NASCIMENTO, Washington Santos (org.). Etnicidade e trânsitos: estudos sobre Bahia e Luanda. Jequié: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Relações Étnicas e Contemporaneidade (UESB); Rio de Janeiro: Áfricas: grupo de pesquisa interinstitucional (UERJ-UFRJ), 2017.). However, the idea of a colonial paradox was being constructed, lived and used in diverse ways and at various levels, insofar as the multiple shifting categories employed in this context were compelled to interact within the institutions regulating social life implemented by colonial expansion. The constant alterations to the legal conditions that encompassed colonial space, especially with respect to those policies intended to establish tighter control of native populations, demonstrate how focusing our analysis on the legislative endeavours of the Portuguese colony does not necessarily help us understand the everyday disputes that influenced the exercise of colonial power. By subverting the narrow focus on these processes, perceiving the different rifts that opened up within this context, envisaging it as a site of disputes and potentially conflictual, and seeking to compare it to the realities existing in the everyday world of the colonial interactions with the native populations of southern Mozambique, especially those legally classified as indigenous, my aim here is to elaborate an analysis that goes beyond observing the existence of the colonial paradox.

Pursuing this approach, in the present article I seek to analyse how the practices designated generically in the sources as ‘batuques’ underwent a simultaneous process of homogenization and scrutinization by diverse agents of Portuguese colonization. This phenomenon is not necessarily perceptible only in the words of these social subjects. Various studies have shown how member of the Grêmio Africano de Lourenço Marques or the Instituto Negrófilo, two of the most important associations of the first half of the twentieth century, composed of important members of the literate African elites who sought to influence Portuguese colonial rule through the press under their control, opposed the performance of ‘batuques’ in the urban space of Lourenço Marques and/or their ritualistic incorporation in celebrations of the Portuguese presence in Mozambican territory. The work of these men was predominantly contrary to the very notion of protecting what they imagined to be local ‘uses and customs,’ advocating their expurgation in favour of a supposed complete and egalitarian assimilation into the European civilization world of all those peoples who found themselves subsumed under the umbrella category of African/colonized (Pereira, 2016PEREIRA, Matheus Serva. “Grandiosos batuques”: identidades e experiências dos trabalhadores urbanos africanos de Lourenço Marques (1890-1930). 2016. Tese (Doutorado em História Social) - IFCH, Unicamp. Campinas, 2016.).

My interest here is in analysing how the colonial agents actively involved in the Portuguese colonization of southern Mozambique dealt with the pre-existing normative rules of the native populations. The so-called batuques formed a significant part of this process. On one hand, the colonial agents insisted on unifying everything they saw as dance and music under the general rubric of batuque. But at the same time, the need for a better understanding of the dominated peoples would produce colonial responses that shifted between a dissection of this term in search of a more accurate apprehension of what was being observed and an incorporation of these practices into the colonial enterprise. The ultimate objective seems to have been to appropriate them in favour of promoting a Portuguese nationalist discourse.

BLACK DRUMS, WHITE EARS

Published under the title As Explorações Portuguesas em Lourenço Marques. Relatórios da Comissão de Limitação da Fronteira de Lourenço Marques, the reports presented by Alfredo Freire de Andrade and José António Matheus Serrano contained their annotations and observations on the expedition they undertook in southern Mozambique between June and August 1891 (Andrade; Serrano, 1894ANDRADE, Alfredo Freire de; SERRANO, José António Matheus. Explorações Portuguesas em Lourenço Marques: Relatórios da Comissão de Limitação da Fronteira de Lourenço Marques. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1894.). The military engineers responsible for the Commission were given the primary objective of constructing landmarks on the border between Mozambique and the Transvaal - present-day South Africa. After completing this territorial demarcation work, the Portuguese commission continued to explore the territory, passing through the districts of Lourenço Marques, Gaza and Inhambane, mostly occupied by Shangana, Tonga and Chopi groups. At that moment, the expedition’s emphasis was on the need to learn about the region to be controlled, both physically and socioculturally, as well as the possibility of forming alliances with local populations.

The establishment of these borders was an important step in recognizing the legitimacy of Portuguese rule over the region against the wishes of other European countries and their colonialist aims. The British influence in Lourenço Marques was considered a risk factor for the possibilities of enforcing Portugal’s claims. The process of delimiting these borders in the final quarter of the nineteenth century was marked by conflicts between the colonizing metropolises as they vied for the regions each would control in Africa. In the Portuguese case, the examples of the Mapa Cor de Rosa (Pink Map), which represented Portugal’s ambitions to control African territories from Angola’s Atlantic coast to Mozambique’s Indian coast, and the British response via an Ultimatum, issued in 1890, which put an end to Portugal’s claims, are emblematic. Both can be taken to constitute some of the main indications of the huge importance and responsibility of the mission commanded by Freire de Andrade and Matheus Serrano in the process of consolidating Portuguese occupation in the present-day territory of southern Mozambique. Unfortunately, the majority of the works on this context possess an analytic approach centred on the issues surrounding the international relations between Portugal and Britain and/or on Portuguese internal policy, leaving out questions related to the African contexts (Santos, 1993-1994SANTOS, Gabriela Aparecida dos. Reino de Gaza: o desafio português na ocupação do sul de Moçambique (1821-1897). São Paulo: Alameda, 2010.).

The British were not the only ones threatening Portugal’s colonial aspirations. The uprisings of local powers against the Portuguese administration also posed serious risks to the Portuguese colonial enterprise in the region. In southern Mozambique, the Gaza Kingdom, founded by the Nguni at the beginning of the nineteenth century through migrations that subjugated other peoples from the region, especially the Chopi, was led by the imposing figure of Gungunhana. Enthroned in 1884, Gungunhana had to face transformations that ended up with his overthrowing and imprisonment by Portuguese troops in 1895 (Santos, 2010SANTOS, Gabriela Aparecida dos. Reino de Gaza: o desafio português na ocupação do sul de Moçambique (1821-1897). São Paulo: Alameda, 2010.).

Freire de Andrade and Matheus Serrano’s insistence on forging a closer relationship with Gungunhana while, at the same time, mapping and establishing contacts with other local chiefs unhappy with the political scenario created by the Gaza Kingdom, reveal the Portuguese interest in the region, as well as the development of an elaborate power game. On one hand, this scenario appeared as ideal for the Portuguese military to successfully establish partnerships with dissatisfied groups; on the other, the resistance to Portuguese power was large with some chiefs (named as régulos by the Portuguese’s) refusing assistance to the expedition’s caravans or rejecting vassalage to Portugal (Andrade; Serrano, 1894ANDRADE, Alfredo Freire de; SERRANO, José António Matheus. Explorações Portuguesas em Lourenço Marques: Relatórios da Comissão de Limitação da Fronteira de Lourenço Marques. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1894., pp. 70 and 134).

The documents elaborated by the Commission reveal the urgent need to establish partnerships in order to weather the storms, as well as the racist vision of the producers of this documentary corpus, and the growing European curiosity in the African culture. However, the Africans are described and photographed almost as one more feature of the landscape. Workers who accompanied the expedition, carrying equipment by river, building boats and risking their lives, the vast majority of them men, were rarely named. On rare occasions the photographic equipment of the Portuguese expedition members was used to capture events such as the night on which “all the Swazis [who worked as porters for the Boers] dance[d] in the encampment” (Andrade; Serrano, 1894ANDRADE, Alfredo Freire de; SERRANO, José António Matheus. Explorações Portuguesas em Lourenço Marques: Relatórios da Comissão de Limitação da Fronteira de Lourenço Marques. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1894., p. 26).

The importance of photographic sources in the History of Africa is well-established. A theoretical-methodological framework to work with these images has matured alongside a growing awareness of the ideological significance of the act of photography. An emphasis can be perceived on photography as a choice informed by the decisions of its author, who, in turn, is impregnated by his or her own culture. A substantial portion of the bibliography is fairly sceptical of the capacity of photographs taken in colonial contexts to tells us much about issues beyond those related to the culture and, especially, the racism of the producers of these images themselves, particularly in the first half of the twentieth century when the practice of photography remained concentrated in European hands (Killingray; Roberts, 1989KILLINGRAY, David; ROBERTS, Andrew. An Outline of Photograph in Africa to ca. 1940. History in Africa, v. 16, p. 197-208, 1989.; Geary, 1990GEARY, Christraud M. Old Pictures, New Approaches: Researching Historical Photographs. African Arts, v. 24, n. 4, 1990.). More recently, investigations have sought to fill the lacuna existing in the use of photographs as sources and objects of analysis relating to Portuguese colonial contexts. Works that use a vast corpus of source images produced over the Portuguese colonial period, like those published in the work edited by Filipa Lowndes Vicente, suggest a wide range of approaches that look to go beyond an analysis of the cultures responsible for producing these sources, seeking interpretations too of those who were photographed (Vicente, 2014VICENTE, Filipa Lowndes (org.). O império da visão: fotografia no contexto colonial português (1860-1960). Lisboa: Ed. 70, 2014.).

The Commission’s picture archive is composed of two photograph albums, totalling 86 images. Documenting the territorial border demarcations, the course of the rivers, the fauna and flora, the encampments and the problems encountered during the expedition or the roads in the city of Inhambane, the expedition’s final destination, was a form of legitimizing and authenticating Portuguese power in the region. For this reason, 72% of the images (or 62) refer to these aspects.3 3 The complete albums are available at http://actd.iict.pt/collection/actd:AHUC141 and http://actd.iict.pt/collection/actd:AHUC148. Consulted 13 September 2018. It is precisely in these images, compared with the descriptions that accompany them, that it becomes possible to reflect on the ways of life of these native populations, the relations established among themselves and how they conceived their relations with the Europeans. The Commission’s meeting with Gungunhana, for example, was extremely tumultuous. Suspicious of the mediator/interpreter, the Portuguese expedition leaders claimed to be surprised and outraged by the subservient manner employed by the Portuguese representatives at Gungunhana’s court when he addressed to the powerful leader of Gaza (Andrade; Serrano, 1894ANDRADE, Alfredo Freire de; SERRANO, José António Matheus. Explorações Portuguesas em Lourenço Marques: Relatórios da Comissão de Limitação da Fronteira de Lourenço Marques. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1894., pp. 139-145). To prove that the meeting had taken place and to promote greater dialogue between the two parties, photographs were taken of Gungunhana and some of his wives.4 4 I am unaware of any researchers who have attributed authorship to these photographs of Gungunhana or provided more information on these images, which are used in most cases in illustrative form. The photos are available at http://actd.iict.pt/view/actd:AHUD5177; http://actd.iict.pt/view/actd:AHUD5179; http://actd.iict.pt/view/actd:AHUD5176; http://actd.iict.pt/view/actd:AHUD5180. Consulted 13 September 2018.

Allowing oneself to be photographed meant more than simply posing in front of a camera. Another time, the chief of Mapanda “resisted [...] letting himself be photographed” by the Portuguese due to his worry about displeasing Gungunhana (as António Ennes stated in the newspaper O Brado Africano, in 1915ENNES, António. Relatório apresentado ao governo por António Ennes (publicado, pela primeira vez, em 1893). O Africano, Lourenço Marques, 4 ago. 1915.). Running the risk of reprisals, however, the chief Novéle did not seem to mind being in contact with the Portuguese commission. Almost at the end of the expedition, Freire de Andrade rested his caravan for a few days on Novéle’s land, located in the Malasche region, close to the city of Inhambane. A tributary of the Massibi chief who had refused to assist the Portuguese campaign, Novéle tried to establish a positive relationship with the Portuguese expedition leader (Andrade; Serrano, 1894ANDRADE, Alfredo Freire de; SERRANO, José António Matheus. Explorações Portuguesas em Lourenço Marques: Relatórios da Comissão de Limitação da Fronteira de Lourenço Marques. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1894., pp. 70-71). Not by chance this is the population most often photographed by the expedition, with seven images. Freire de Andrade also produced some descriptions of local customs, such as the belief in the gagáo - a practice referring to divination - and wearing their hair “partly shaven [...] almost always letting it grow in longitudinal and usually parallel lines” (Andrade; Serrano, 1894ANDRADE, Alfredo Freire de; SERRANO, José António Matheus. Explorações Portuguesas em Lourenço Marques: Relatórios da Comissão de Limitação da Fronteira de Lourenço Marques. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1894., pp. 70-71).5 5 The photographs of the ‘Boys of Malashe’ is available at http://actd.iict.pt/view/actd:AHUD5170. Consulted 13 September 2018.

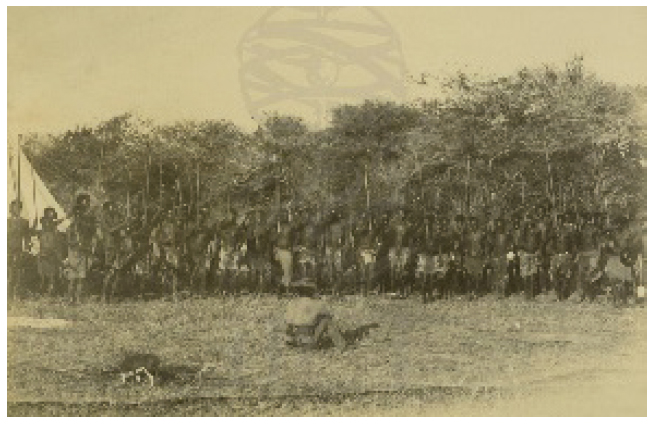

Novéle’s display of dissatisfaction with the wars caused by Gungunhana, combined with his rapprochement with Freire de Andrade’s commission, showed how the chief understood that the Portuguese presence in the region could be useful to his own political objective of regaining the independence lost following submission to the Gaza Kingdom. As a way of persuading the Portuguese to adopt measures in their favour, as well as narrating and inflating the feats of his people, he sent men and women to sing and dance in the Commission’s camp “almost every night.” Despite describing them as a monotonous drone, these presentations by the ‘warrior people’ forced Freire de Andrade to conceal his own fear. The military engineer, who in subsequent years would become one of the most emblematic figures of the Portuguese campaign of occupation in southern Mozambique, was frightened by the warriors who almost touched him as they advanced clutching their assegais, pretending to attack “their absent enemies” (Andrade; Serrano, 1894ANDRADE, Alfredo Freire de; SERRANO, José António Matheus. Explorações Portuguesas em Lourenço Marques: Relatórios da Comissão de Limitação da Fronteira de Lourenço Marques. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1894., p. 72). At the end of his stay in Malasche, the propaganda campaign launched by Novéle seems to have had an effect. The Commission’s leader became convinced that the region was home to “a fine warlike people.” To reinforce his partnership with the Portuguese government, Novéle provided the expedition members with food, promised to supply personnel and accompanied the expedition with “more than four hundred Negroes [...] for an hour and a half’s walk [..] with Kaffir music” (Andrade; Serrano, 1894ANDRADE, Alfredo Freire de; SERRANO, José António Matheus. Explorações Portuguesas em Lourenço Marques: Relatórios da Comissão de Limitação da Fronteira de Lourenço Marques. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1894., p. 75).

The two photographs taken of this procession reveal that the sounds of what Freire de Andrade generically called ‘Kaffir music’ were produced by a large drum and xylophones called timbila (singular: mbila) by the players themselves. The latter musical instrument was used by orchestras funded by chiefs that primarily functioned as an important marker of cultural belonging employed in the ngodo (plural: migodo) performances, “a set of songs and instrumental pieces arranged into a composition” (Vail; White, 1991VAIL, Leroy; WHITE, Landeg. The Development of Forms. The Chopi Migodo. In: VAIL, Leroy; WHITE, Landeg. Power and the Praise Poem: Southern African Voices in History. Virginia: University Press of Virginia, 1991. , p. 112). In this sense, despite the report indicating at specific moments a regional origin to the populations with which they established contact, the photographs allow us to go further and indicate a potential ethnic belonging of the chief Novéle. It is plausible to imagine that he considered himself Chopi, a group that sold its independent to the Gaza Kingdom for a high price (Harries, 1981HARRIES, Patrick. Slavery, Social Incorporation and Surplus Extraction: The Nature of Free and Unfree Labour in South-East Africa”. The Journal of African History, v. 22, n. 3, p. 309-330, 1981.).

Available at the Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical (IICT), the two photographs to emerge from this encounter are captioned “Batuque em Malashe.” The images taken by the Commission were not published with its report. Only in 2013, when the IICT made them available online, was it possible to access the images produced by the expedition. Despite the laudable efforts made to digitalize such a huge body of documents, most of them produced by colonial Portuguese scientific bodies, the photographs from the collection still need to be investigated. The institute itself recognizes this necessity, informing users that it lacks any precise identification of the authors of the photographs, only possessing the name of the leaders of the expeditions responsible for producing the documentation. This may explain why the captions to these photographs describe them as “Batuque in Malashe,” despite not having been named as such in the report.

The mismatch between the term used in the caption and the one that appears in the report contextualizing the production of the image opens the way for a reflection on the term ‘batuque,’ used to define the dances and music presented by peoples categorized as indigenous in the Portuguese colony at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. The process of naming what was seen had two distinct effects. On one hand, it unified everything that was seen and heard issuing from the bodies, vocal chords and musical instruments under the generic designation of batuque. This homogenization of music and dance is similar to the homogenization central to the process of racialization of social relations generated by colonialism. At the same time, this form of dancing and music was defined pejoratively and taken to represent and pervade the nature of the individuals involved. On the other hand, the curiosity of metropolitan circles in what was considered exotic in the colonies, combined with the need to establish a rationalized colonial process that could enhance the forms of domination, produced supposedly precise descriptions, which sought to disentangle the local practices summarily incorporated into the Portuguese language through use of the term batuque.

The racializing homogenization of local cultural practices, combined with a process of incorporating and differentiating the Portuguese colonial project in Mozambique, Portuguese ethnographic studies classified music as “the amusement that most impressed the Negro,” since a “batuque dominates and excites all the indigenous” (Lima, 1934LIMA, Fernando de Castro Pires. Contribuição para o estudo do folclore de Moçambique. Separata de: Revista de etnografia, Porto: Museu de Etnografia e História, n. 14, 1934., p. 9). The author of these words continues his deprecatory description of the practitioners of these forms of dancing and singing. It was, he writes, commonplace for “men and women of any age, even children” to abandon everything and venture “deep into the forest towards the site” where the batuques were happening. The “strange dances” were “almost always [...] accompanied by pornographic songs.” The “batuques” ended up “usually in a collective drunkenness” (Lima, 1934LIMA, Fernando de Castro Pires. Contribuição para o estudo do folclore de Moçambique. Separata de: Revista de etnografia, Porto: Museu de Etnografia e História, n. 14, 1934., p. 9).

Unifying a diverse range of songs and dances, irrespective of the region from which they originated, of the population groups with whom they had contact and the musical and dance practices of the people they sought to describe, use of the term batuque was widely disseminated by the Portuguese. The word was also associated with a supposed African essence and the local predilection for “obscene sayings and [...] grimaces” (Lima, 1943LIMA, Américo Pires de. Explorações em Moçambique. [1918] Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, 1943. , p. 52). The labels used by those who focused on analysing local forms of expression tended to distance them from the urban periphery, reading the dance steps through a prism of eroticization and generally disparaging the musical talent of the performers.

This view of these practices circulated not only in metropolitan intellectual and academic spheres. Deprecatory opinions of what were conventionally called batuques were also expressed in books and newspapers published in Lourenço Marques. As José dos Santos Rufino, an important figure in the city’s journalistic world at the beginning of the twentieth century, affirmed: “the purpose of batuque [...] is not what it may seem - to dance: it is to drink.” To the ears of the Portuguese Rufino, their music was classified as “simple noise” and the “lyrics [...] almost always meaningless” (Rufino, 1929RUFINO, José dos Santos (ed.). Álbuns fotográficos e descritivos da colônia de Moçambique. V. 10: Raças, usos e costumes indígenas. Fauna Moçambicana. Lourenço Marques: J. S. Rufino, 1929., p. VI). Others, as João Albasini, one of the most important representatives of a small literate African elite, wrote in Lourenço Marques newspapers on everyday life and colonial policies. Many of his articles adopted interpretations similar to those of Rufino. One of his main complaints was the presence of cultural practices performed out of place, when made in urban spaces. In 1914, Albasini wrote that in the canteens and facilities of Munhuana, a suburb of Lourenço Marques described by him as the land “of vices and batuques,”6 6 O Africano, Lourenço Marques, 6 July 1918. World Newspaper Archive (WNA). it was enough to make the “slight effort of opening one’s eyes” to see that “wild batuques were danced that emphasized the posterior, wriggling the hips in erotic movements ‘capable of making a dead man drool.’”7 7 O Africano, Lourenço Marques, 13 May 1914. WNA.

THE NAME AND THE THINGS: ONE WORD FOR MANY PRACTICES

In fact, what was called batuque by those unversed in these forms of expression might mean many things. Despite using the generic term ‘Kaffir music,’ what Freire de Andrade witnessed was a Chopi orchestra. Furthermore, it seems to me that during the evenings when he was camped on Novéle’s land, the military engineer was honoured with two different kinds of performance. The first was a representation of war exploits in which, holding their weapons, warriors demonstrated their ferocity. The second corresponded to a ngodo. The diversity encompassed by the term batuque did not pass entirely unperceived by those unfamiliar with these practices. With eyes and ears trained in a Eurocentric perspective, those who worked to produce materials capable of translating the local cultural diversity into the Portuguese language were probably the first to highlight the difficulties inherent to this process.

As Patrick Harries explains, an important aspect of the modernization process in Africa implemented by European imperial conquest was the classification of details into units that homogenized diversity, seeking to rationalize this world into the structures of European thought. Based on this form of seeing the world, linguists, ethnographers and many others classified the Africans into different ethnic groups that were sometimes more a reproduction of the European discourse of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries rather than a reflection of local realities (Harries, 1988HARRIES, Patrick. The Roots of Ethnicity: Discourse and the Politics of Language Construction in South-East Africa. African Affairs, v. 87, n. 346, p. 25-52, Jan. 1988.). From these attempts to expand and accumulate information referring to sociocultural aspects of the African societies of southern Mozambique, agents of colonization strove to provide descriptions that could assist future colonization. The literature produced by these men on the everyday life of domination is recurrently explained as a necessity for greater efficiency of the colonial State. In this sense, there existed - at least as a stated objective - a practical function in this accumulation of knowledge on music and dance since it sought to generate interpretations capable of supplementing the day-to-day administration of the local populations. However, western science as a whole and, more specifically the scientific parameters prevailing in Portugal at the start of the twentieth century, provided tools that unified diverse aspects under identical rubrics, revealing a widespread ignorance of what existed and an almost inoperative capacity to encompass diversity. At the same time, it revealed an arrogant presumption that announced the porosity of the foundations to the Portuguese colonial enterprise in the region.

The colonial administrator António Augusto Pereira Cabral - who held the post of Civil Secretary of the government of Inhambane district between 1908 and 1914, and the Secretary of Indigenous Affairs in Lourenço Marques between 1915 and 1925 - on compiling a book on the “races, uses and customs of the indigenous peoples from the province of Mozambique” emphasized the hypothesis that the word batuque was “derived from the Portuguese batucar, to hammer, to beat repeatedly,” explaining why it was used by “Europeans [for] any dance in which the indigenous people immerse themselves to have fun.” However, since his book’s objective was to improve the tools used by future colonial employees in their interactions with local populations, the author warned that employment of the term was “inaccurate [...] since it is a word entirely alien” to the native languages. Furthermore, the author was also careful to emphasize that each dance and/or music possessed its own name, varying among the different populations, and not all of them constituted ‘fun,’ some of them being “a ritualistic precept” (Cabral, 1925CABRAL, António Augusto P. Raças, usos e costumes dos indígenas da província de Moçambique. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1925., p. 40).8 8 According to Rui Mateus Pereira, the work and actions of “Pereira Cabral essentially help us comprehend the endeavour of the authorities of this new colonial era to codify uses and customs” (PEREIRA, 2001, p. 137).

The difficulty in naming what was seen and heard was symptomatic of the context in which Portuguese rule was being implemented in southern Mozambique. The final quarter of the nineteenth century abounded in exercises in translation that sought to make different aspects of the local languages more familiar to the ears and writing of European grammars. The pioneerism of this learning undertaken by men engaged in this field, like the missionary and ethnographer Henri Junod,9 9 Henri Junod dedicated much of his academic life to writing books that translated the native orality of groups that he studied into grammatical elements. See CHATELAIN; JUNOD, 1909. was accompanied by the creation of bodies capable of fomenting the intellectual instruments that could ensure the continuation of Portugal’s overseas presence, such as the work performed by the Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, founded in 1875 (Guimarães, 1984GUIMARÃES, Ângela. Uma corrente do colonialismo português. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte, 1984.). In 1895, for example, with the objective of assisting the “expeditionary forces in Lourenço Marques” who had fought against the Gaza Kingdom, the Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, in partnership with the Ministry of War, published a “conversation guide in Portuguese, English and Landim” with some “notions of Landim grammar” (Raposo, 1895RAPOSO, Alberto Carlos de P. Noções de gramática landina: breve guia de conversação em português, inglês e landim. Lisboa: Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, 1895.).

Other examples similar to this guide can be found throughout the first half of the twentieth century, many of them focused on specific sectors in interaction with the native populations. The nurse of the Mozambique Health Corps, Guidione de Vasconcelos Matsinhe, for example, published a book with phrases related to the environment of western medical consultations and treatments. His aim was to assist the professional health workers who worked with the populations of southern Mozambique speaking the Ronga, Shangana and Xitsua languages (Matsinhe, 1946MATSINHE, Guidione de Vasconcelos. O auxiliar do médico e do enfermeiro: vocabulário das línguas ronga, shangaan e xitsua. Lourenço Marques: Minerva Comercial, 1946.). Another author who produced something similar was the priest António Lourenço Farinha, a Portuguese missionary who published the book Elementos de Gramática Landim (shironga). Dialeto indígena de Lourenço Marques. In the final part of the work, Farinha devotes space to a series of small phrases exemplifying possible dialogues between speakers of the Portuguese and native languages. Ironically, these imagined dialogues paid little attention to the topic of converting African souls to Catholicism. The phrases, most of them imperatives associated with domestic chores, dwelt on the day-to-day exploitation of the local labour force (Farinha, 1946FARINHA, Padre António Lourenço. Elementos de Gramática Landina (shironga): dialeto indígena de Lourenço Marques. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1946.).

Dictionaries were also important tools in the process of colonizing and exploiting the local workforce.10 10 This is a process that had occurred since the construction of the networks of slave and commodity trading in the Atlantic world. However, in the context of the European empires in Africa in the nineteenth century, it acquired a new meaning. On the importance of the definition of a written language common to the majority of the native populations of the geographic region analyzed here and the different processes of colonization, see HARRIES, 2007. Incapable of defining practices with the same precision afforded by local forms of naming, the authors who worked to translate the huge diversity of native dances and music into the familiar environment of the language of the Portuguese colonizer ended up condensing the complexity of these practices into just a few terms from the Portuguese lexicon. In the Dicionário português-cafre-tetense published in 1900, its author, the priest Victor José Courtois, sought to translate into written form the orality of peoples from the Zambeze river valley region in the centre of Mozambique. In it, the words for dances, music and batuque appear correlated with a wide variety of terms employed to designate these forms. For instance, the word batuque, in Portuguese, could be translated as “t’unga; - of dancing, ng’oma; mbondo; chiwere; nkuwiri; tsengua; chinkufu; murumbi; kuendje; - of war, mbiriwiri; chindzete; dza- che” (Courtois, 1900COURTOIS, Victor José. Dicionário Português-cafre-tetense ou idioma falado no Distrito de Tete e na vasta região do Zambeze inferior. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade, 1900., p. 71). Ng’oma and t’unga do not appear merely as translations for batuque. The former could also be employed like the verbs ‘dance’ and ‘hammer’ (batucar). The latter, according to the dictionary, could have the meaning of ‘dance’ or ‘music’ in a more comprehensive sense (Courtois, 1900COURTOIS, Victor José. Dicionário Português-cafre-tetense ou idioma falado no Distrito de Tete e na vasta região do Zambeze inferior. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade, 1900., pp. 132 and 324).

These similarities, encountered here and there, including in relation to words used by cultural practices with African roots in Brazil, can be explained by the dissemination of the Bantu language family throughout virtually the entire region that today corresponds to the nation state of Mozambique. However, this does not mean that they were exactly the same thing. In specific contexts, these words and the phenomena they described took on distinct meanings (Slenes, 1992SLENES, Robert W. “Malungu, ngoma vem!”: África coberta e descoberta do Brasil. Revista USP, n. 12, p. 48-67, 1992.).

For the regions of southern Mozambique (Gaza, Lourenço Marques and Inhambane) the Dicionários shironga-português e português-shironga. Precedidos de uns breves elementos de gramática do dialeto Shironga, falado pelos indígenas de Lourenço Marques, coordinated by E. Torre do Vale and published in 1906, are among the most complete for the period analysed. The author dedicated his work to the “need to produce a dictionary in which the Portuguese can learn the indigenous dialect, and another in which the indigenous people can learn our language” (Valle, 1906VALLE, E. Torre. Dicionários shironga-português e português-shironga: precedidos de uns breves elementos de gramática do dialeto Shironga, falado pelos indígenas de Lourenço Marques. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1906.). Unlike António Augusto Pereira Cabral, who presumes that the term batuque had been employed by Europeans due to the virtual absence of a specific term in the native languages for the act of beating something, Torre do Vale’s dictionary records the existence of the verb gongondya, signifying to “beat the door; beat on a drum; beat repeatedly.” According to his dictionary, the Portuguese word batuque could be translated as ‘nkino’ or ‘nthlango,’ the former referring to “dance; batuque” and the latter to “dance; toy; amusement; spectacle; game.” Both words - nkino and nthlango - as well as ‘ngoma’ were also employed by the author as synonyms of dance. Ngoma, for its part, was something more than a dance, since it could be considered as a term for ‘drum’ or ‘circumcision ritual.’ Along with these words from the universe of the so-called batuques, the reader was advised to seek out the meanings of the words “Bunanga; Mutimba; Shindekan-deka; Shiwombelo; Mutshongolo; Gila; Sabela; Nhlawo.” These, in turn, amplified the world that the Portuguese lexicon insistently demarcated in narrow fashion through the expression batuque. After all, Bunanga was a specific dance referred to as a “fanfare of horns.” Shindekandeka was a dance practiced by women only. Mutshongolo is presented as an “indigenous dance, imported from the north,” while Gila and Sabela formed important practices relating to the native logics of power, the former being presented to re-enact “war exploits” and the latter used “when a chief is crowned” (Valle, 1906VALLE, E. Torre. Dicionários shironga-português e português-shironga: precedidos de uns breves elementos de gramática do dialeto Shironga, falado pelos indígenas de Lourenço Marques. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1906., pp. 59, 68, 110, 115, 117, 120, 125, 141, 149, 196 and 215).

The difficulty of transcribing these multiple realities, combined with the specific characteristics of colonial domination, very often stimulated a process of folklorization of native sociocultural practices. Fernando de Castro Pires de Lima, a physician and prominent Portuguese ethnographer, endeavoured to combine the existing diversity in a generic category of ‘Mozambican folklore.’ To achieve this aim, he took as a base only the accounts of employees of the Companhia de Moçambique, located in Zambezia, central Mozambique, and the observations he himself was able to make with the ‘indigenous people’ brought by the company to the Overseas Exhibition held in Porto in 1934. According to Lima, it was “necessary to study very seriously the habits and customs of the Negro so that Whites can understand him better” (Lima, 1934LIMA, Fernando de Castro Pires. Contribuição para o estudo do folclore de Moçambique. Separata de: Revista de etnografia, Porto: Museu de Etnografia e História, n. 14, 1934., p. 6). Without ever having set foot on Mozambican soil, he produced a description of the most common instruments in the territory:

One frequently used musical instrument is the Mbira, which is a kind of a box open on one side with iron tines of various sizes attached to a lid and secured by wires. They also use the Chindongane, which is formed from a bamboo rod bent by a brass wire tied to its ends; the Nhanga, constructed from small sections of cane of various sizes, which are blown in alternation; the Maranja, which is a cane flute; the Dindua, which is formed by a larger bow than the Chindogare, also held taut by a brass wire on which a gourd is tied that functions as an amplifier. They also possess the Mpuita, which is an instrument composed of a cylinder of sheet metal or iron, and the Ntuco, made from a horn in which a hole is drilled close to the tip. However the main instrument is the Marimba. The marimba is composed of small bars of wood of various sizes, connected to each other by leather straps. Below each wooden bar are small interconnecting gourds fastened with wax. The gourds are of various sizes corresponding to a musical scale. These gourds are perforated and the hole covered with a resistant film, almost always taken from the intestines of an animal, the most commonly used being the membrane of a bat wing. The gourds and pieces of wood are placed in a frame also made of wood, which allows it to be transported easily. The Marimba is played using two wooden mallets with virgin rubber tips. The commonest Marimba has ten wooden bars, which correspond to ten notes and ten scales, major or minor. The pace and rhythm are clearly defined and, as well as indigenous music, they play European music. The top chiefs have Marimba orchestras in their settlements composed of four, six, eight or ten Marimbaists. This does not mean that orchestras of twelve, eighteen or twenty Marimbas do not exist, with a leader, or, we could say, an orchestral conductor. (Lima, 1934LIMA, Fernando de Castro Pires. Contribuição para o estudo do folclore de Moçambique. Separata de: Revista de etnografia, Porto: Museu de Etnografia e História, n. 14, 1934., p. 10)

Similar forms of these instruments were described by other authors. However, different names were used to designate them. It seems plausible to suppose that these were instruments disseminated throughout the region of present-day Mozambique, as well as some of its territorial neighbours, and that they acquired distinct names among each of the populations that used them. What Fernando de Lima described by the term ntuco, for example, is very similar to what Henri Junod called a xipalapala, which was “the official trumpet for the convocations [...] with which subjects were assembled in the capital” (Junod, 2009JUNOD, Henry. Usos e costumes dos Bantu. Tomo I - Vida social. Campinas: Unicamp, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, 2009., p. 334). Similarly, Eduardo do Couto Lupi, a military officer who acted in the suppression of the sultanates resisting the Portuguese presence in northern Mozambique, claimed that the Macuas possessed something analogous, called a “palapata, an antelope horn with a lateral perforation that functioned as a cornet” (Lupi, 1907LUPI, Eduardo do Couto. Breve memória sobre uma das capitanias-mores do distrito de Moçambique. Capitão-mor d’Angoche desde 4 de julho de 1903 a 5 de dezembro de 1905. Lisboa: Tipografia do Anuário Comercial, 1907., p. 108).

In the case of the dances, a variety of names was also used, despite the fact they possessed very similar characteristics in terms of both performance and meaning. One dance that had a pronounced sensory effect on those who saw it was what the Portuguese came to call in a generic and simultaneously homogenizing fashion ‘war dances.’ Perhaps due to their intimidating display of force, presented in specific contexts, the writers contemporary to the process of colonization who focused their narratives or studies on native dance frequently concentrated their attention on these forms. Henri Junod again provides a good example. He described the kugila or kugiya, which was frequently performed by the peoples located to the south of the Save river, as a “simulacrum of acts of bravery practiced by the soldiers who killed enemies on the battlefields” (Junod, 2009JUNOD, Henry. Usos e costumes dos Bantu. Tomo I - Vida social. Campinas: Unicamp, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, 2009., p. 364). Others like António Cabral claimed that these were called msongola or gila and originated from the South African Zulus. Considered important in terms of demonstrating the power of the chiefs, “the indigenous peoples dress[ed] extravagantly” and presented the dances to “any indigenous chief or authority figure”; the men interpreted the battles brandishing their weapons, while the women participated by singing about the enacted feats (Cabral, 1925CABRAL, António Augusto P. Raças, usos e costumes dos indígenas do Distrito de Inhambane. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1910., p. 40).11 11 The author also describes this dance in CABRAL, 1910, pp. 28-36.

All these forms supposedly typical to these populations known at the time as the barongas are not very different from those performed by the porters of the Boer caravans during the 1891 Portuguese expedition or by the people of the chief Novéle from the Chopi group. As António Cabral states, the Chopi dances were called lifolo. Accompanied by the timbila, the practitioners decorated themselves as in the msongola, singing and dancing “beating their shields on the ground” and performing “a series of leaps and gestures simulating combat with an enemy” (Cabral, 1925CABRAL, António Augusto P. Raças, usos e costumes dos indígenas do Distrito de Inhambane. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1910., p. 41).12 12 Cabral likewise claims to have witnessed the shivunvuri, in the Tete region, central Mozambique. According to the author, the latter was “an imitation of the chigombela.”

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

It is important to emphasize that my objective here has not been to analyse each musical expression and dance performed by the various population groups existing during the period that the Portuguese colonial presence was becoming consolidated in southern Mozambique, much less the complexity and importance of the distinct ceremonies in which they were employed. Analysing the different types of dances and musical instruments employed in these practices, such as the huge variety of drums existing across Mozambique’s territory, the diverse sizes of timbila played by the Chopi and many other instruments, has likewise not been at the core of my present inquiry.

In other occasion, I have called attention to the spectacularization of these practices through their incorporation into celebrating the Portuguese empire. This process was concomitant with the homogenization of native forms of songs and dances - a process not entirely controlled by the colonial power, serving as an ideal moment to make demands or as a demonstration that this control was not as effective as it presumed to be (Pereira, 2016PEREIRA, Matheus Serva. “Grandiosos batuques”: identidades e experiências dos trabalhadores urbanos africanos de Lourenço Marques (1890-1930). 2016. Tese (Doutorado em História Social) - IFCH, Unicamp. Campinas, 2016.). The exercise of appropriation conceived by colonial forces, including via the consolidation of forms of naming what was seen, was unable to inhibit the responses of those who sang and danced in clear opposition to the racist contrivances used to expurgate their practices.

In the context of the colonial domination of southern Mozambique between 1890 and 1940, an audience composed mostly of Europeans/whites, but also the small literate African elite, worked hard to classify and describe the dances and music of groups like the Chopi or the Shangana, basing their classifications of these performatics on ears and eyes trained in a specific sensory corpus. This specific manner of analysing in detail the bodies and sounds of the southern African populations of Mozambique, promoted by Eurocentric senses of those that strove to describe their dance and musical practices, interpreted these forms of expression and communication in a pejorative and racist form. Although they perceived local diversity and complexity, the Portuguese interpreters of the southern African world of Mozambique insisted on characterizing African sounds and body movements in a deprecatory way. Just as the multiplicity of African socio-political identities, experiences and organizational forms were reduced to juridical denominations that obliterated the heterogeneity of the so-called assimilated or indigenous peoples, the Portuguese colonists strove to homogenize the variety of musical and dance practices of southern Mozambique by converging on a specific denomination. In the exercise of the colonial enterprise, the plurality of these practices underwent a process of attempted erasure, perceptible in the homogenizing and generic use of the term batuque to describe them and through the deprecatory connotation that the lexicon carried in that context.

REFERÊNCIAS

- ALVES, Vera Marques. Arte popular e nação no Estado Novo: a política folclorista do Secretariado de Propaganda Nacional. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, 2013.

- ANDRADE, Alfredo Freire de; SERRANO, José António Matheus. Explorações Portuguesas em Lourenço Marques: Relatórios da Comissão de Limitação da Fronteira de Lourenço Marques. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1894.

- CABRAL, António Augusto P. Raças, usos e costumes dos indígenas do Distrito de Inhambane. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1910.

- CABRAL, António Augusto P. Raças, usos e costumes dos indígenas da província de Moçambique. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1925.

- CARDÃO, Marcos. Fado tropical: o luso-tropicalismo na cultura de massas (1960-1974). Lisboa: Ed. Unipop, 2014.

- CENTRO de Estudos Africanos, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane. O mineiro moçambicano: um estudo sobre a exportação de mão de obra em Inhambane. [1977]. Maputo: Centro de Estudos Africanos, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, 1998.

- CHATELAIN, Charles W.; JUNOD, Henry A. A Pocket Dictionary, Thonga (Shangaan)-English; English-Thonga (Shangaan), Preceded by an Elementary Grammar. Lausanne: G. Bridel, 1909.

- COOPER, Frederick. Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005.

- COURTOIS, Victor José. Dicionário Português-cafre-tetense ou idioma falado no Distrito de Tete e na vasta região do Zambeze inferior. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade, 1900.

- ENNES, António. Relatório apresentado ao governo por António Ennes (publicado, pela primeira vez, em 1893). O Africano, Lourenço Marques, 4 ago. 1915.

- FARINHA, Padre António Lourenço. Elementos de Gramática Landina (shironga): dialeto indígena de Lourenço Marques. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1946.

- GEARY, Christraud M. Old Pictures, New Approaches: Researching Historical Photographs. African Arts, v. 24, n. 4, 1990.

- GUIMARÃES, Ângela. Uma corrente do colonialismo português. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte, 1984.

- HARRIES, Patrick. Junod e as sociedades africanas: impacto dos missionários suíços na África Austral. Maputo: Paulinas, 2007.

- HARRIES, Patrick. The Roots of Ethnicity: Discourse and the Politics of Language Construction in South-East Africa. African Affairs, v. 87, n. 346, p. 25-52, Jan. 1988.

- HARRIES, Patrick. Slavery, Social Incorporation and Surplus Extraction: The Nature of Free and Unfree Labour in South-East Africa”. The Journal of African History, v. 22, n. 3, p. 309-330, 1981.

- HARRIES, Patrick. Work, Culture, and Identity: Migrant Laborers in Mozambique and Souht Africa, c. 1860-1910. Portsmouth: Heinemann; Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press; London: James Currey, 1994.

- JERÓNIMO, Miguel Bandeira. Livros brancos, almas negras: a “Missão Civilizadora” do colonialismo português (c.1870-1930). Lisboa: ICS (Imprensa de Ciências Sociais), 2009.

- JUNOD, Henry. Usos e costumes dos Bantu. Tomo I - Vida social. Campinas: Unicamp, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, 2009.

- KILLINGRAY, David; ROBERTS, Andrew. An Outline of Photograph in Africa to ca. 1940. History in Africa, v. 16, p. 197-208, 1989.

- LIMA, Américo Pires de. Explorações em Moçambique. [1918] Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, 1943.

- LIMA, Fernando de Castro Pires. Contribuição para o estudo do folclore de Moçambique. Separata de: Revista de etnografia, Porto: Museu de Etnografia e História, n. 14, 1934.

- LUPI, Eduardo do Couto. Breve memória sobre uma das capitanias-mores do distrito de Moçambique. Capitão-mor d’Angoche desde 4 de julho de 1903 a 5 de dezembro de 1905. Lisboa: Tipografia do Anuário Comercial, 1907.

- MACAGNO, Lorenzo. O discurso colonial e a fabricação dos ‘usos e costumes’. Antonio Ennes e a geração de 95. In: FRY, Peter (org.). Moçambique, ensaios. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. UFRJ, 2001.

- MATSINHE, Guidione de Vasconcelos. O auxiliar do médico e do enfermeiro: vocabulário das línguas ronga, shangaan e xitsua. Lourenço Marques: Minerva Comercial, 1946.

- MATOS, Patrícia Ferraz de. As Côres do Império: representações raciais no Império Colonial Português. Lisboa: ICS (Imprensa de Ciências Sociais), 2006.

- PENVENNE, Jeanne Marie. African Workers and Colonial Racism: Mozambican Strategies and Struggles in Lourenço Marques, 1877-1962. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 1995.

- PENVENNE, Jeanne Marie. Women, Migration & the Cashew Economy in Southern Mozambique: 1945-1975. Oxford: James Currey, 2015.

- PEREIRA, Matheus Serva. “Grandiosos batuques”: identidades e experiências dos trabalhadores urbanos africanos de Lourenço Marques (1890-1930). 2016. Tese (Doutorado em História Social) - IFCH, Unicamp. Campinas, 2016.

- PEREIRA, Matheus Serva; NASCIMENTO, Washington Santos. Etnicidades e os Outros em contextos coloniais africanos: reflexões sobre as encruzilhadas entre História e Antropologia. In: SANTANA, Marise de; FERREIRA, Edson Dias; NASCIMENTO, Washington Santos (org.). Etnicidade e trânsitos: estudos sobre Bahia e Luanda. Jequié: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Relações Étnicas e Contemporaneidade (UESB); Rio de Janeiro: Áfricas: grupo de pesquisa interinstitucional (UERJ-UFRJ), 2017.

- PEREIRA, Rui Mateus. A ‘Missão etognósica de Moçambique’. A codificação dos ‘usos e costumes indígenas’ no direito colonial português. Notas de investigação. Cadernos de Estudos Africanos, Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Internacionais (CEI-IUL) do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), v. 1, p. 126-177, 2001.

- RAPOSO, Alberto Carlos de P. Noções de gramática landina: breve guia de conversação em português, inglês e landim. Lisboa: Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, 1895.

- RUFINO, José dos Santos (ed.). Álbuns fotográficos e descritivos da colônia de Moçambique. V. 10: Raças, usos e costumes indígenas. Fauna Moçambicana. Lourenço Marques: J. S. Rufino, 1929.

- SANTOS, Gabriela Aparecida dos. Reino de Gaza: o desafio português na ocupação do sul de Moçambique (1821-1897). São Paulo: Alameda, 2010.

- SANTOS, Maria Emília M. Ultimatum, espaços coloniais e formações políticas africanas. África. Revista do CEA - USP, São Paulo, v. 16-17, n. 1, 1993-1994.

- SLENES, Robert W. “Malungu, ngoma vem!”: África coberta e descoberta do Brasil. Revista USP, n. 12, p. 48-67, 1992.

- VAIL, Leroy; WHITE, Landeg. The Development of Forms. The Chopi Migodo. In: VAIL, Leroy; WHITE, Landeg. Power and the Praise Poem: Southern African Voices in History. Virginia: University Press of Virginia, 1991.

- VALLE, E. Torre. Dicionários shironga-português e português-shironga: precedidos de uns breves elementos de gramática do dialeto Shironga, falado pelos indígenas de Lourenço Marques. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1906.

- VICENTE, Filipa Lowndes (org.). O império da visão: fotografia no contexto colonial português (1860-1960). Lisboa: Ed. 70, 2014.

- ZAMPARONI, Valdemir. De escravo a cozinheiro: colonialismo & racismo em Moçambique. Salvador: EDUFBA/Ceao, 2007.

-

1

Visiting fellow at Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa (ICS-Lisboa). The research on which this article is based received funding from FAPESP (Process 2018/05617-0).

-

2

Along these lines, see MACAGNO, 2001MACAGNO, Lorenzo. O discurso colonial e a fabricação dos ‘usos e costumes’. Antonio Ennes e a geração de 95. In: FRY, Peter (org.). Moçambique, ensaios. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. UFRJ, 2001.; COOPER, 2005COOPER, Frederick. Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005..

-

3

The complete albums are available at http://actd.iict.pt/collection/actd:AHUC141 and http://actd.iict.pt/collection/actd:AHUC148. Consulted 13 September 2018.

-

4

I am unaware of any researchers who have attributed authorship to these photographs of Gungunhana or provided more information on these images, which are used in most cases in illustrative form. The photos are available at http://actd.iict.pt/view/actd:AHUD5177; http://actd.iict.pt/view/actd:AHUD5179; http://actd.iict.pt/view/actd:AHUD5176; http://actd.iict.pt/view/actd:AHUD5180. Consulted 13 September 2018.

-

5

The photographs of the ‘Boys of Malashe’ is available at http://actd.iict.pt/view/actd:AHUD5170. Consulted 13 September 2018.

-

6

O Africano, Lourenço Marques, 6 July 1918. World Newspaper Archive (WNA).

-

7

O Africano, Lourenço Marques, 13 May 1914. WNA.

-

8

According to Rui Mateus Pereira, the work and actions of “Pereira Cabral essentially help us comprehend the endeavour of the authorities of this new colonial era to codify uses and customs” (PEREIRA, 2001PEREIRA, Rui Mateus. A ‘Missão etognósica de Moçambique’. A codificação dos ‘usos e costumes indígenas’ no direito colonial português. Notas de investigação. Cadernos de Estudos Africanos, Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Internacionais (CEI-IUL) do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), v. 1, p. 126-177, 2001., p. 137).

-

9

Henri Junod dedicated much of his academic life to writing books that translated the native orality of groups that he studied into grammatical elements. See CHATELAIN; JUNOD, 1909CHATELAIN, Charles W.; JUNOD, Henry A. A Pocket Dictionary, Thonga (Shangaan)-English; English-Thonga (Shangaan), Preceded by an Elementary Grammar. Lausanne: G. Bridel, 1909..

-

10

This is a process that had occurred since the construction of the networks of slave and commodity trading in the Atlantic world. However, in the context of the European empires in Africa in the nineteenth century, it acquired a new meaning. On the importance of the definition of a written language common to the majority of the native populations of the geographic region analyzed here and the different processes of colonization, see HARRIES, 2007HARRIES, Patrick. Junod e as sociedades africanas: impacto dos missionários suíços na África Austral. Maputo: Paulinas, 2007..

-

11

The author also describes this dance in CABRAL, 1910CABRAL, António Augusto P. Raças, usos e costumes dos indígenas do Distrito de Inhambane. Lourenço Marques: Imprensa Nacional, 1910., pp. 28-36.

-

12

Cabral likewise claims to have witnessed the shivunvuri, in the Tete region, central Mozambique. According to the author, the latter was “an imitation of the chigombela.”

-

25

English version: David Rodgers

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

08 Apr 2019 -

Date of issue

Jan-Apr 2019

History

-

Received

10 May 2018 -

Accepted

18 Sept 2018

Source: [Photographic album no. 10]. Comissão de Delimitação de Fronteira de Lourenço Marques 1890-91. Arquivo Científico Tropical. Digital Repository (ACT/DR). Available at:

Source: [Photographic album no. 10]. Comissão de Delimitação de Fronteira de Lourenço Marques 1890-91. Arquivo Científico Tropical. Digital Repository (ACT/DR). Available at:  Source: [Photographic album no. 10]. Comissão de Delimitação de Fronteira de Lourenço Marques 1890-91. ACT-DR. Available at:

Source: [Photographic album no. 10]. Comissão de Delimitação de Fronteira de Lourenço Marques 1890-91. ACT-DR. Available at: