Abstract

The extent of ADP-ribosylation in rectal cancer was compared to that of the corresponding normal rectal tissue. Twenty rectal tissue fragments were collected during surgery from patients diagnosed as having rectal cancer on the basis of pathology results. The levels of ADP-ribosylation in rectum cancer tissue samples (95.9 ± 22.1 nmol/ml) was significantly higher than in normal tissues (11.4 ± 4 nmol/ml). The level of NAD+ glycohydrolase and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activities in rectal cancer and normal tissue samples were measured. Cancer tissues had significantly higher NAD+ glycohydrolase and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activities than the control tissues (43.3 ± 9.1 vs 29.2 ± 5.2 and 6.2 ± 1.6 vs 1.6 ± 0.4 nmol mg-1 min-1). Approximately 75% of the NAD+ concentration was consumed as substrate in rectal cancer, with changes in NAD+/ADP-ribose metabolism being observed. When [14C]-ADP-ribosylated tissue samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, autoradiographic analysis revealed that several proteins were ADP-ribosylated in rectum tissue. Notably, the radiolabeling of a 113-kDa protein was remarkably greater than that in control tissues. Poly(ADP)-ribosylation of the 113-kDa protein in rectum cancer tissues might be enhanced with its proliferative activity, and poly(ADP)-ribosylation of the same protein in rectum cancer patients might be an indicator of tumor diagnosis.

Rectal cancer; ADP-ribosylation; NAD+; NAD+ glycohydrolase; Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

Braz J Med Biol Res, March 2005, Volume 38(3) 361-365

Changes in NAD/ADP-ribose metabolism in rectal cancer

L. Yalcintepe1, L. Turker-Sener1, A. Sener2, G. Yetkin2, D. Tiryaki1 and E. Bermek1

1Department of Biophysics, Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University, Capa-Istanbul, Turkey

2Department of General Surgery, Sisli Etfal Training and Research Hospital, Sisli-Istanbul, Turkey

Patients and Methods

Patients and Methods

References

References

Correspondence and Footnotes

Correspondence and Footnotes

Correspondence and Footnotes

Correspondence and Footnotes

Abstract

The extent of ADP-ribosylation in rectal cancer was compared to that of the corresponding normal rectal tissue. Twenty rectal tissue fragments were collected during surgery from patients diagnosed as having rectal cancer on the basis of pathology results. The levels of ADP-ribosylation in rectum cancer tissue samples (95.9 ± 22.1 nmol/ml) was significantly higher than in normal tissues (11.4 ± 4 nmol/ml). The level of NAD+ glycohydrolase and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activities in rectal cancer and normal tissue samples were measured. Cancer tissues had significantly higher NAD+ glycohydrolase and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activities than the control tissues (43.3 ± 9.1 vs 29.2 ± 5.2 and 6.2 ± 1.6 vs 1.6 ± 0.4 nmol mg-1 min-1). Approximately 75% of the NAD+ concentration was consumed as substrate in rectal cancer, with changes in NAD+/ADP-ribose metabolism being observed. When [14C]-ADP-ribosylated tissue samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, autoradiographic analysis revealed that several proteins were ADP-ribosylated in rectum tissue. Notably, the radiolabeling of a 113-kDa protein was remarkably greater than that in control tissues. Poly(ADP)-ribosylation of the 113-kDa protein in rectum cancer tissues might be enhanced with its proliferative activity, and poly(ADP)-ribosylation of the same protein in rectum cancer patients might be an indicator of tumor diagnosis.

Key words: Rectal cancer, ADP-ribosylation, NAD+, NAD+ glycohydrolase, Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

Introduction

Different lines of evidence indicate that cellular NAD+ content influences cellular responses to genomic damage by multiple mechanisms. NAD+ is consumed directly of the transfer of ADP-ribose groups and synthesis of ADP-ribose polymers and cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR). ADP-ribosylation of cellular proteins is a post-translational modification reaction involving the transfer of ADP-ribose groups from NAD+ to acceptor proteins (1). ADP-ribosylation reactions are classified as mono(ADP)-ribosylation and poly(ADP)-ribosylation depending upon the length of the transferred group (1). Moreover, these modifications differ in terms of the chemical nature of the ADP-ribosyl protein bond (i.e., cytoplasm/cell membrane versus nucleus), enzyme responsible for the formation of the linkage, and biological significance. The best characterized mono-ADP-ribosyltransferases are catalyzed by certain bacterial toxins (1) that alter critical metabolic and regulatory pathways.

The enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which is abundant in nuclei, is important as a regulatory enzyme (2). PARP has been reported to be involved in cell proliferation (3), cell differentiation (1), carcinogenesis (4), and DNA repair (5). It is known that both tumor and rapidly proliferating cells have higher PARP activity levels than normal or resting cells. Recent studies have suggested that poly(ADP)-ribosylation might play a role in oral cancer and might be used as a tumor marker (6). Cyclic ADP-ribose is a potent calcium-releasing agent that may also mediate signaling pathways leading to apoptosis or necrosis (7,8). NAD+ metabolism is a target for both the prevention and treatment of cancer (9). Increases in ADP-ribosylation, NAD+ glycohydrolase (NADase) and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activities which are involved in the direct catabolic pathway of NAD+ turnover can lead to rapid consumption of NAD+ and affect the size of the NAD+ pool.

In the present investigation, ADP ribosylation of tissue samples from rectal cancer patients has been evaluated as an indicator of tumor diagnosis.

Patients and Methods

Tissue samples

Fresh rectum tissues were obtained from patients with rectal cancer. After surgery, tissues were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen until use. Normal tissue was taken from the same rectum material at a site distant from the cancer tissue and evaluated for the presence of cancer cells. Only primary cancer samples were examined. The patients included in the study had not received prior radiation or chemotherapy. Frozen tissues were first ground using a mortar and pestle, and then suspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 10% (w/w) glycerol, 10 mM MgCl2, 300 units/ml DNAse I, and protease inhibitors (10 µg/ml aprotinin, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, and 2 mM PMSF). The extract obtained in this step is referred to as the crude (or total) protein extract. After centrifugation of the total extract for 30 min at 1000 g to eliminate non-lysed cells, the supernatant was used for assays (10).

NAD + glycohydrolase and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activities

NADase activity in protein extracts was measured by the fluorimetric method of Muller et al. (11). The extracts were incubated in 400 µl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, and 200 µM 1,N6-ethano-NAD+. Data acquisition was started concomitantly with the addition of enzyme. Activity was measured on the basis of the initial slope of the reaction. Fluorescence measurements were performed using a Perkin-Elmer (Buckinghamshire, UK) fluorescence spectrophotometer, LS45 (lex = 310 and lem = 410).

ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity was assayed by using NGD+ as substrate and measuring the production of cyclic GDP-ribose (cGDPR) as an increase in fluorescence. cGDPR, the guanine nucleotide equivalent of cADPR, is resistant to hydrolysis (in contrast to cADPR) (12) and is also fluorescent, allowing continuous fluorimetric monitoring of the reaction. The extracts were incubated for 1 h at 37ºC in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 50 µM NGD+. The excitation wavelength was set at 300 nm and the emission was measured at 410 nm with a Perkin-Elmer LS45 spectrometer. The amount of cGDPR produced was determined by comparing the fluorescence intensity with that of cGDPR standards.

NAD + content

NAD+ concentration was determined by conversion of NAD+ to NADH using the alcohol dehydrogenase reaction and assuming a molar extinction coefficient for NADH of 6.22 x 106 cm2 mol-1 at 340 nm (13). Briefly, the samples were incubated at 25ºC in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.3, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, and 1% (v/v) ethanol, and, after the addition of alcohol dehydrogenase (5000 U/ml), the increase in A340 nm was monitored with a Shimadzu spectrophotometer UV-1601 (Kyoto, Japan).

ADP-ribosylation of tissue extracts

ADP-ribosylation was assayed as described (14). Briefly, 30-µl reaction mixtures containing 20-µl tissue sample, 10 µM (14C)-NAD and 8 mM CaCI2 were incubated for 2 h at 37ºC. After incubation, 20-µl aliquots were plated onto GF/A filters (Whatman, Houston, TX, USA), and CCl3COOH-precipitable radioactivity was determined as described (14). Thereafter, aliquots from reaction mixtures containing 50 µg protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE (15). After electrophoresis, proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, destained in 7% acetic acid and 30% methanol, dried, and exposed to Kodak X-Omat K films at -70ºC for autoradiographic analysis.

Data are reported as means ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed by the Student paired t-test. Protein concentration was determined with a Bio-Rad protein assay dye reagent kit (St. Louis, MO, USA) using bovine serum albumin as standard.

Results and Discussion

Figure 1 shows the extent of ADP-ribosylation detected in the samples from cancer versus normal tissues. The extent of ADP-ribosylation in cancer tissue samples (mean: 95.9 ± 22.1 nmol/ml) was 8-fold higher than in normal tissue (mean: 11.4 ± 4 nmol/ml). NADase and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activities were similarly higher in cancer tissue than in control samples: 43.3 ± 9.1 vs 29.2 ± 5.2 nmol mg-1 min-1 NAD hydrolyzed and, correspondingly, 6.2 ± 1.6 and 1.6 ± 0.4 nmol mg-1 min-1 cADPR formed. NAD+ levels dropped from 345.5 ± 60.7 in normal tissue to 83.9 ± 36.24 µM in cancer tissue samples (Figure 1A).

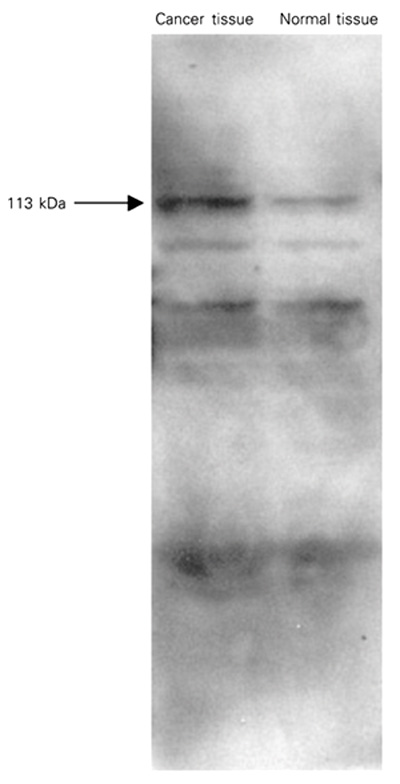

When [14C]-ADP-ribosylated tissue samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, subsequent autoradiographic analysis revealed the presence of several radiolabeled protein bands (Figure 2). The radiolabeling of a 113-kDa protein band which is considered to correspond to PARP was considerably enhanced in cancer tissue samples. Elevated NADase and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activities in cancer tissues may reflect the differences in NADase activities regarding the availability of NAD+ for poly(ADP)-ribosylation which may account, at least in part, for the difference in the extent of poly(ADP)-ribosylation between normal and cancer tissue. Since poly(ADP-ribose) synthesis is in the direct catabolic pathway of NAD+ turnover, increases in poly(ADP-ribose) synthesis can lead to rapid NAD+ consumption and affect the size of the NAD+ pool. Jacobson et al. (16) have provided evidence that the reduction in NAD+ for the synthesis of poly(ADP-ribose) and the synthesis of the polymer is stimulated by molecular damage to DNA. Recent studies have indicated increases in PARP activity concomitant with increased ADP-ribosylation during oral carcinogenesis (6), in human peripheral blood lymphocytes from leukemia patients and in tissue from ovarian cancer (17).

CD38 is considered to be an activation marker and also acts as a bifunctional ectoenzyme that catalyzes the conversion of NAD+ to cADPR and the hydrolysis of cADPR to ADPR. CD38 is expressed in activated T- and B-lymphocytes. Accordingly, elevated NADase and ADP-ribose cyclase activities may reflect a lymphocytic infiltration of tumor tissue. Indeed, Kim et al. (18) have shown that CD38 expression in uterine cervix cancers is primarily due to lymphocyte infiltration. Lymphocytic tumor infiltration indicates a host response and is generally associated with a favorable prognosis. CD38-catalyzed generation of cADPR is associated with regulation of intracellular Ca2+ levels and chemotaxis in neutrophils and is required for innate inflammatory immune responses (19). On the other hand, CD38 expression in leukemia may be correlated with the rate of malignant cell proliferation, histological tumor grade, and patient survival (20). Jacobson et al. (9) showed that nicotinamide and resulting cellular NAD+ concentrations could modulate the expression of the tumor suppressor protein P53 in human breast, skin, and lung cells.

The results of the present investigation suggest that some changes occurring in NAD+ metabolism may have implications regarding tumor development and prognosis.

NAD+ levels (A), ADP-ribosylation (B), NAD+ glycohydrolase (C) and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activities (D) in tissue samples from rectal cancer patients. Each point is the mean of dublicate assays. The mean value is shown by the horizontal line. Data are reported as means ± SD.

ADP-ribosylation of rectal cancer tissue samples. Tissue samples (50 µg protein) were incubated with 10 µM (14C)-NAD. [14C]-ADP-ribosylated samples were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gels were then subjected to autoradiographic analysis as described in Material and Methods. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Address for correspondence: L. Yalcintepe, The Terry Fox Laboratory, British Columbia Cancer Agency, 601 West 10th Av.,Vancouver, V5Z 1L3, Canada. Fax: +1-604-844-6600. E-mail: lemany@istanbul.edu.tr or lemanyalcintepe@hotmail.com

Research supported by the Research Fund of the University of Istanbul (Project B-322/121099). Received April 13, 2004. Accepted January 6, 2005.

- 1. Ueda K & Nayaishi O (1985). ADP-ribosylation. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 54: 73-100.

- 2. Judson IR & Threadgill MD (1993). Poly (ADP-ribosylation) as target for cancer chemotherapy. Lancet, 342: 632.

- 3. Menegazzi M, Gerosa F, Tommasi M, Uchida K, Miwa M, Sugimura T, Suzuki H & Gelosa F (1988). Induction of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase gene expression in lectin-stimulated human T lymphocytes is dependent on protein synthesis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 156: 995-999.

- 4. Tsujiuchi T, Tsutsumi M, Denda A, Kondoh S, Nakae D, Maruyama H & Konishi Y (1990). Possible involvement of poly ADP-ribosylation in phenobarbital promotion of rat hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis, 11: 1783-1797.

- 5. Durkacz BW, Omidiji O, Gray DA & Shall S (1980). (ADP-ribose)n participates in DNA excision repair. Nature, 283: 593-596.

- 6. Das BR (1993). Increased ADP-ribosylation of histones in oral cancer. Cancer Letters, 73: 29-34.

- 7. Vu CQ, Coyle DL, Tai H-H & Jacobson MK (1997). Intramolecular ADP-ribose transfer reactions and calcium signalling. In: Haag F & Koch-Nolte F (Editors), ADP-Ribosylation in Animal Tissues: Structure, Function, and Biology of Mono-ADP-Ribosyltransferases and Related Enzymes. Plenum Press, New York, 381-338.

- 8. Vu CQ, Coyle DL, Jacobson EL & Jacobson MK (1997). Intracellular signalling by cyclic ADP-ribose in oxidative cell death. FASEB Journal,11: A1116 (Abstract).

- 9. Jacobson EL, Shieh WM & Huang AC (1999). Mapping the role of NAD metabolism in prevention and treatment of carcinogenesis. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 193: 69-74.

- 10. Ceni C, Pochon N, Brun V et al. (2003). CD38-dependent ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity in developing and adult mouse brain. Biochemical Journal, 370: 175-183.

- 11. Muller CD, Tarnus C & Schuber F (1984). Preparation of analogues of NAD+ as substrates for a sensitive fluorimetric assay of nucleotide pyrophosphatase. Biochemical Journal, 223: 715-721.

- 12. Graeff RM, Mehta K & Lee HC (1994). GDP-ribosyl cyclase activity as a measure of CD38 induction by retinoic acid in HL-60 cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 205: 722-727.

- 13. Albeniz IU, Nurten R & Bermek E (1997). ADP-ribosylation of serum proteins: elevated levels in neoplastic cases due to altered NAD/ADP-ribose metabolism. Cancer Investigation, 15: 217-223.

- 14. Ustundag-Albeniz I, Nurten R & Bermek E (1996). ADP-ribosylation of serum proteins: evaluation as a potential tumor marker. Cancer Letters,108: 239-245.

- 15. Laemmli UK (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227: 680-685.

- 16. Jacobson MK, Levi V, Juarez-Salinas H, Barton RA & Jacobson EL (1980). Effect of carcinogenic N-alkyl-N-nitroso compounds on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolism. Cancer Research, 40: 1797-1802.

- 17. Singh N (1991). Enhanced poly ADP-ribosylation in human leukemia lymphocytes and ovarian cancers. Cancer Letters, 58: 131-135.

- 18. Han MK, Kwark OS, Jang KY, Lee DG, Oh BC, An NH & Kim UH (1999). Increase of NADase activity in uterine cervix cancers is caused by infiltration of lymphocytes. Cancer Letters, 146: 201-205.

- 19. Partida-Sanchez S, Cockayne DA, Monard S et al. (2001). Cyclic ADP-ribose production by CD38 regulates intracellular calcium release, extracellular calcium influx and chemotaxis in neutrophils and is required for bacterial clearance in vivo Nature Medicine, 7: 1209-1216.

- 20. Koehler M, Behm F, Hancock M & Pui CH (1993). Expression of activation antigens CD38 and CD71 is not clinically important in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia, 7: 41-45.

Correspondence and Footnotes

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

08 Mar 2005 -

Date of issue

Mar 2005

History

-

Received

13 Apr 2004 -

Accepted

06 Jan 2005