Abstract

The objective of this study was to analyze the trend of epidemiological and operational indicators of leprosy in Brazil, from 2001 to 2017. This was a time series study involving nine indicators. The inflection point regression model was used. Decreasing trends were observed for the following: general detection (−4.8%), children under 15 (−3.7%), prevalence (−7.0%), and grade 2/million inhabitants (−3.5%). The proportion of individuals with grade 2 disability showed an upward trend (2.0%) from 2001 as well as contacts examined from 2003 (5.0%). The proportions of cure and of individuals with a degree of disability assessed at the time of the diagnosis and the cure showed a stationary behavior. Although advances are noted, there are still challenges to be overcome.

KEYWORDS

Leprosy; Mycobacterium leprae; Time series studies

Leprosy is a neglected tropical disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae.11 Cruz RCS, Buhrer-Sékula, Penna MLF, Penna GO, Talhari S. Leprosy: current situation, clinical and laboratory aspects,treatment history and perspective of the uniform multidrugtherapy for all patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:764-77. Leprosy in Brazil in the 21st century 747 Over the past three decades, the number of cases of the disease has been progressively decreasing. In 2017 alone, 150 countries reported 210,671 new cases of the disease; 80.2% of these were reported by Brazil, India, and Indonesia. That same year, Brazil accounted for 26,875 (92.3%) of the new cases registered in the Americas.22 World Health Organization. Global leprosy update, 2017: reducing the disease burden due to leprosy. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;93:445-56.

Due to this unfavorable epidemiological scenario, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Global Strategy 2016–2020, based on three pillars: a) strengthening government control, coordination, and partnership; b) fighting leprosy and its complications; c) combating discrimination and promoting inclusion.33 World Health Organization. Global leprosy update, 2016: accelerating reduction of disease burden. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92:501-20. In this sense, the monitoring of epidemiological indicators is of special relevance for the control of leprosy and the success of the strategies developed.

This study aimed to analyze the temporal evolution of the epidemiological and operational indicators of leprosy in Brazil, from 2001 to 2017.

This was an ecological time series study. Nine epidemiological and operational leprosy indicators in Brazil, obtained from Datasus (http://datasus.saude.gov.br/), were included in the study (Table 1).44 Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância das Doenças Transmissíveis. Diretrizes para vigilância, atenção e eliminação da Hanseníasecomo problema de saúde pública: manual técnico-operacional [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2016 [cited 2018 Oct 19]. Available from: http://www.saude.pr.gov.br/arquivos/File/Manual de Diretrizes Eliminacao Hanseniase.pdf.

http://www.saude.pr.gov.br/arquivos/File...

,55 Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde. Casosde Hanseníase (SINAN). [cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: http://www2.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/index.php?area=0203&id=31032752.

http://www2.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/index...

After collection, the inflection point regression model was used for temporal analysis. The annual percent change (APC) was calculated. The trends were classified as increasing, decreasing, or stationary. A 95% confidence interval and a significance level of 5% were considered. As this study used data in public domain, the need for approval from a research ethics committee was waived.

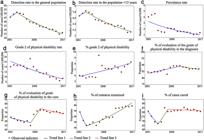

Between 2001 and 2017, 652,764 new cases of leprosy were reported in Brazil. Of these, 41,191 (6.31%) were in individuals under 15 years of age. Since 2013, the detection rates in the general population and in those under 15 years showed a downward trend (APC = −5.9% and −5.0%; respectively). When the complete period was considered, the percentages of reduction were smaller (−4.8% and −3.7%, respectively). Despite the advances, in 2017 the endemic was classified as high in the general population (12.94/100,000) and in children under 15 years old (3.72/100,000). The prevalence rate, in turn, has shown a linear trend of reduction since 2001 (APC = −7.0%), decreasing from 3.99 to 1.35/10,000 inhabitants (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Among the indicators related to the presence of physical disability, the rate of new leprosy cases with grade 2 physical disability at diagnosis has shown a downward trend since 2001 (APC = −3.5%), decreasing from 14.00 to 9.39/1 million inhabitants. In turn, the proportion of individuals diagnosed with grade 2 showed a significant growth trend (APC = 2.0%), going from 6.0% in 2001 to 8.3% in 2017 (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

The proportions of individuals assessed at the time of the diagnosis and the cure presented a stationary temporal pattern in the studied period. In all years of the time series, the proportion of subjects evaluated was considered regular (75%–89.9%) at the time of diagnosis and precarious (<75%) at the time of discharge due to cure (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

The proportion of contacts examined showed a growth trend since 2003 (APC = 5.0%), going from 43.9% in 2003 to 78.9% in 2017, thus being considered regular. In turn, the proportion of individuals cured showed a steady trend in the period, with 81.6% in 2001 and 81.2% in 2017, thus being considered regular (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Even considering the advances in the fight against leprosy, the findings show important challenges to be overcome by Brazil. The first one is the high annual percentages of reduction in general detection (−4.8%), detection in children under 15 years old (−3.7%), and detection of grade 2 disability (−7.0%). As this is a chronic disease with slow evolution and difficult control, such sharp annual reductions should be viewed with concern. For example, in 2005, over 49,000 cases of the disease were registered in the general population; the following year, slightly over 43,000. Brazilian studies point to the high hidden prevalence of the disease in Brazil, which has prevented the identification of the real number of patients in the country.55 Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde. Casosde Hanseníase (SINAN). [cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: http://www2.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/index.php?area=0203&id=31032752.

http://www2.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/index...

In the present study, the increase in the proportion of grade 2 cases at diagnosis reinforces this underdiagnosis hypothesis.66 Salgado CG, Barreto JG, Silva MB, Goulart IMB, Barreto JA, Nery JA, et al. Are leprosy case numbers reliable? Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:135-7.,77 Bernardes-Filho F, Paula NA, Leite MN, Abi-Rached TLC, Vernal S, Silva MBD, et al. Evidence of hidden leprosy in a sup-posedly low endemic area of Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2017;112:822-8.

The second Brazilian challenge is the need to qualify the surveillance system. There is a lack of qualified outpatient clinics and personnel for the proper monitoring of cases, which compromises the assessment of the degree of disability, the monitoring of neural functions, the management of reactions, and the proper examination of contacts, fundamental tools for interrupting the transmission chain of this disease.88 Souza CDF, Santos FGB, Marques CS, Leal TC, Paiva JPS, EMCF Araújo. Spatial study of leprosy in Bahia, Brazil, 2001-2012: anapproach based on the local empirical Bayesian model. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2018;27:e2017479.–1010 Souza CDF, Luna CF, Magalhães MAFM. Spatial modeling of leprosy in the State of Bahia and its social determinants: a study of health inequities. Ann Bras Dermal. 2019;94:183-92.

Based on the present findings, the authors advocate the need for the development of plans and strategies that would allow early diagnosis of the disease and favor the systematic monitoring of patients, with emphasis on early diagnosis and prevention of physical disabilities.

-

Financial supportNone declared.

-

☆

How to cite this article: Souza CDF, Paiva JPS, Leal TC, UrashimaGS. Leprosy in Brazil in the 21st century: analysis of epidemiologicaland operational indicators using inflection point regression. An BrasDermatol. 2020;95:743-747.

-

☆☆

Study conducted at the Center for the Study of Social and Pre-ventative Medicine, Department of Medicine, Universidade Federalde Alagoas, Campus Arapiraca, Arapiraca, AL, Brazil.

References

-

1Cruz RCS, Buhrer-Sékula, Penna MLF, Penna GO, Talhari S. Leprosy: current situation, clinical and laboratory aspects,treatment history and perspective of the uniform multidrugtherapy for all patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:764-77. Leprosy in Brazil in the 21st century 747

-

2World Health Organization. Global leprosy update, 2017: reducing the disease burden due to leprosy. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;93:445-56.

-

3World Health Organization. Global leprosy update, 2016: accelerating reduction of disease burden. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92:501-20.

-

4Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância das Doenças Transmissíveis. Diretrizes para vigilância, atenção e eliminação da Hanseníasecomo problema de saúde pública: manual técnico-operacional [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2016 [cited 2018 Oct 19]. Available from: http://www.saude.pr.gov.br/arquivos/File/Manual de Diretrizes Eliminacao Hanseniase.pdf

» http://www.saude.pr.gov.br/arquivos/File/Manual de Diretrizes Eliminacao Hanseniase.pdf -

5Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde. Casosde Hanseníase (SINAN). [cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: http://www2.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/index.php?area=0203&id=31032752

» http://www2.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/index.php?area=0203&id=31032752 -

6Salgado CG, Barreto JG, Silva MB, Goulart IMB, Barreto JA, Nery JA, et al. Are leprosy case numbers reliable? Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:135-7.

-

7Bernardes-Filho F, Paula NA, Leite MN, Abi-Rached TLC, Vernal S, Silva MBD, et al. Evidence of hidden leprosy in a sup-posedly low endemic area of Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2017;112:822-8.

-

8Souza CDF, Santos FGB, Marques CS, Leal TC, Paiva JPS, EMCF Araújo. Spatial study of leprosy in Bahia, Brazil, 2001-2012: anapproach based on the local empirical Bayesian model. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2018;27:e2017479.

-

9Barbieri RR, Sales AN, Hacker MA, Nery JAC, Dupre ND, Machado AM, et al. Impact of a reference center on leprosy control undera decentralized Evidence of hidden leprosy in a supposedly lowendemic area of Brazil public health care policy in Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:1-11.

-

10Souza CDF, Luna CF, Magalhães MAFM. Spatial modeling of leprosy in the State of Bahia and its social determinants: a study of health inequities. Ann Bras Dermal. 2019;94:183-92.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

30 Nov 2020 -

Date of issue

Nov-Dec 2020

History

-

Received

3 Apr 2019 -

Accepted

17 Sept 2019